Eric Garner uttered “I can’t breathe” eleven times on July 17, 2014 when he died at the hands of the New York City Police. Five years later, on May 13, 2019, the disciplinary trial of the police officer responsible for Garner’s death began and the video footage of the incident was presented as evidence.1 Officer Daniel Pantaleo was tried and found guilty of using a prohibited method of physical restraint (the chokehold), which has been repeatedly determined as a violation of the Fourth Amendment as an excessive use of force.2 Garner’s last words have become a rallying cry for the #BlackLivesMatter community against police brutality across the United States.3 Unfortunately, cases like Garner’s have been regular news stories in American media over the past ten years. The shooting of the unarmed teenager Trayvon Martin in 2012 and the subsequent acquittal of his murderer, neighborhood watchman George Zimmerman, gave rise to the #BlackLivesMatter movement.4 Other deaths of unarmed Blacks, from Michael Brown and Garner two years later to Breonna Taylor and George Floyd in 2020, have established and reinforced the #BlackLivesMatter movement as a national call for change in how over-policed communities of color are treated by law enforcement in the United States.

America’s history is rife with racial tension. Continued discussions around rights, opportunities, and civil liberties across racial lines have been captured in cultural objects since imagery of slave ships, auctions, and plantation life were produced and circulated in the early-seventeenth century. In addition to drawings that were primarily used for newspaper advertisements and announcements, documentation of the earliest photographs of slaves, daguerreotypes from 1850, resurfaced in the attic of Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnology in 1976.5 Images like these contribute to the racial tapestry that has been woven over the course of generations. As visual mediums evolved, the cinema also captured representations of social struggle on the topic of race since the early-twentieth century. One such film was released in 1936 by a film director who had recently emigrated from Germany. That director was Fritz Lang and the film was titled Fury.

Lang’s international legacy is comprised of canonized cinematic masterpieces like Metropolis (1927), M (1931), and Hangmen Also Die (1943). Born and raised in Vienna, Lang’s directorial trajectory led him to Berlin, where he created some of his most famous work and became a German citizen, before emigrating by way of Paris to his final destination of Hollywood. Fury (1936), Lang’s initial American film, was the first to incorporate the medium of the moving image in the form of courthouse evidence in a cinematic production.6 In this depiction, Lang presents the spectator with the undeniable manipulability of the medium, how it translates the representation of reality on a screen, and calls the spectator to question if this representation can or should be trusted. In this article, I discuss the impact of framing shots and the editing of footage in the creation of a narrative by filmmakers, as we see in Fury, in addition to more contemporary concerns pertaining to the potential fabrication of footage through editing and modifying the content of filmed media. One of the many accomplishments of Fury is the way it frames the medium of the moving image as the closest we can get to reliably capturing events. This, however, comes with the caveat of the medium’s easy manipulability. Today, we continue to see how filmic evidence is often received by their consumers with distrust.

While filmic evidence is permitted in the courtroom in Fury, there is a staggering number of contemporary court cases regarding social injustices pertaining to race that often declare video recordings as being biased or otherwise inadmissible. Through the presentation of filmic information in Fury, Lang foreshadows the contemporary dilemma of questioning the validity and representation of truth accomplished by video recordings in the courtroom today. Lang’s first American film successfully presents its audience with an example of how the medium of the moving image shifts from a status of reliable, recorded real-time moments to one of untrustworthy, subjective spectatorship. This is most prominent in contemporary media through the events that provoked the #BlackLivesMatter movement into existence, reintroducing the topic of police brutality into active social discourse as cases like Garner’s murder continue to illuminate a systemic problem.

In this article, I provide a brief introduction to Fury and Lang before diving into the history of lynching and mob mentality in America. I then discuss Lang’s introduction of filmic evidence in a courtroom setting as featured in Fury. I address how the medium of film is rooted in a fundamental problem: it provides access to sequential events in one medium that offers an opportunity to relive moments in time accurately yet is problematized by its easy manipulability. Lending itself to the manipulation of its consumer by way of including cultural and contextual framing, camera angles, uncertain authorship, and content modification, the validity of filmic footage is therefore often received as questionable. This setup will prepare us for discussion of the history of oppressed groups that have fallen victim to violence by those in positions of power, which will gradually guide us through the evolution of the #BlackLivesMatter movement. This focus correlates with heightened social discourse on the topic of contemporary police brutality and its prevalence in marginalized communities. I present contemporary conversations around the First and Fourteenth Amendments and how they extend to filming the police by both civilians and the use of police body cameras to capture events of police misconduct. After commenting on how these discussions spill over into general public relations with law enforcement, I close by outlining how racial tensions call for a continuous grappling with how the moving image is awarded or denied reliability.

Fury and Fritz Lang

Lang’s Fury was released in theaters in 1936, two years after the director arrived in Hollywood and signed a contract to work at the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio (MGM).7 Starring Spencer Tracy as Joe Wilson and Sylvia Sydney as his fiancée Katherine Grant, the film follows the life of a man who is falsely identified as a member of a kidnapping gang and ends up in a jail cell in the Midwestern town of Strand. Idle gossip quickly morphs into an enraged mob that decides to take matters into their own hands to see Joe brought to justice, resulting in an attempted lynching by fire. The mob attacks the jail, effectively removing the police from the equation, and setting the building on fire to accomplish the job of lynching the believed-to-be kidnapper.

Arriving just in time to see Joe peering through his jail cell’s barred window, Katherine is the only witness willing to testify seeing Joe in the jail engulfed by flames. However, Joe survives the lynching due to an explosion which frees him rather than sealing his fate. Keeping his survival a secret, Joe and his two brothers attempt to legally try and convict twenty-two members of the mob for murder. However, after being confronted by Katherine, his brothers, and eventually with his own conscience, Joe arrives in the courtroom just in time to spare the twenty-two people on trial from what Joe calls a “legal death”—what would have been denied to him had he perished at the hands of the mob.

Fury evolved out of a story by Norman Krasna titled Mob Rule, which was based on an actual mob lynching in 1933. Two men, believed to be the kidnappers of an heir to a well-known department store company, were forcibly taken by an enraged mob from their jail cells and hung as an example of vigilante justice.8 Assigned to direct the film by MGM, Lang collaborated with Bartlett Cormack to write the screenplay.9 One of the proposed changes as the film morphed from Mob Rule and into Fury was the idea of making the protagonist a Black man who would be wrongly accused of raping a White woman.10 Considered too socially charged, the idea was rejected by MGM. Nevertheless, Joe’s character underwent numerous fundamental changes before the most fitting demographic for the character was realized. Reporting that Lang originally wanted Joe to be a lawyer, film critic and Lang’s biographer Lotte Eisner states that the decision was struck down by the film’s producer, Joseph L. Mankiewicz.11 Eisner details the considerations that informed Joe’s character:

The hero must be an ordinary man of the people, a kind of Everyman or, in the local idiom, “Joe Doe”…The average American is most interested in things that happen to the average American, people with the same background as himself. The spectator wants to identify with the hero.12

Pointing to some of the social commentary already embedded in Fury, Joe’s designation as an Every- (read: White) man is rooted in a plot that thematizes a considerable fear of the average Black American in the 1930s. Eisner comments on the topic of lynching at the core of the plot in addition to the stance held by MGM on how Black characters could be incorporated into the script. She writes, “[it would not] have been acceptable that the man who is almost lynched should be black, regardless of the fact that black lynchings occurred again and again in real life. At MGM Mayer [sic] had decreed that ‘Coloured [sic] people can only be used as shoe-shine boys or porters’.”13 The film therefore includes Black minor characters, all of whom almost fall to the backdrop but successfully provide some cultural commentary for those looking for it.14

The handful of Black characters featured in Fury range in contexts and roles that fall under parallel background roles as MGM’s suggestions of shoe-shine boys and porters—in what were considered “menial occupations.”15 The first Black minor character is seen giving a patron at a local barbershop a shoe-shine as rumors of Joe’s arrest begin circulating. The second appears as Katherine listens to a Black woman singing while removing laundry from the line as two Black men listen along. Yet another Black shoe-shine is seen quickly jumping out of the way as the mob exits the bar in which they conspire to lynch Joe.16 And the final minor Black character in Fury is a barkeep who serves Joe a drink as he begins to unravel under the weight of his actions. These diminished representations of what it meant to be Black in America in the 1930s still help in painting a picture of the social climate around racism during the period. Indeed, one of the film’s enduring legacies is in its ability to represent the social climate in regard to racial tensions at the time of its release that is still applicable today.

Figure 1: Fury. Shoe-Shine Jumps Out of the Way as the Mob Leaves the Bar and Heads for the Town Jail. Source: Fritz Lang, Fury, 1936.

Source: Fritz Lang, Fury, 1936.

Despite maintaining Krasna’s original demographic of Joe being a middle-aged White man, there are other signs of racial tension embedded in the film beyond the minor Black characters. These include the emphasis of the term lynching instead of murder in the narrative; Eisner reports that the director did his due diligence in regard to educating himself on the prevalence of lynchings in American society as he was preparing for Fury.17 Some of his research included broadening his news clippings-collection, which he used to aid in his transition to American life and culture, to include those of comparable stories of lynchings.18 It is probable that the historical practice of yanking imprisoned Blacks out of jail cells to be hanged by members of the Ku Klux Klan also served as a significant influence on the development of the original story’s central plot.19 Eisner comments on one clipping that Lang saw as a missed opportunity. She states, “he [regretted] that he noticed one of these clippings too late: a report of how San Francisco drivers of long-distance busses would stand by their vehicles attracting customers by shouting: ‘Get in, get in! There’ll be a lynching in San José at 10 o’clock’.”20 Film historian Robert A. Armour also comments on the role of lynching in the film but argues that, while lynching is central to the plot, the film provides much more to analyze than the racially-motivated violence itself. Armour writes,

The lynching takes place at roughly the midpoint in the film. Something like half the film is devoted to events that take place after the ‘murder.’ And Lang’s emphasis in this part of the film is not so much on the guilt of the murderers as it is on the dark struggle of Joe as he wrestles with his need for revenge and his guilt and isolation that result from his actions. While lynching is an issue here, it is the effect of the lynching on the participants that is the major theme of the film.21

Reading the attempted lynching as a vehicle that reveals deeper commentary, Armour argues that the subsequent actions and psychological struggle faced by Joe, Katherine, and the citizens of Strand are at the core of the film.22 Joe’s evening walk following a confrontation with his brothers and Katherine leads to guilt-driven hallucinations.23 It is this mounting guilt, coupled with his fear of a future of isolation, that drives Joe to appear at the courthouse at the end of the film. Joe’s arrival to the courthouse reveals his survival of the lynching as he admits to participating in the trial and conviction of the twenty-two defendants. After confronting himself, Joe sees that he cannot go on living a lie and instead chooses a future as a part of society.

Armour contends that this concluding scene provides lasting commentary as he relates the subject matter to his own contemporary context of the 1970s. He argues that audiences perceived Joe’s admission of his tampering with the trial and his coming to terms with his guilt as relatable. For Armour, “it is in the second part of the film that Lang’s social message endures. Lynching is not the social problem in America it was in 1936, but mass guilt and revenge have become more important.”24 In this rereading of Fury, I regard the subject of lynching found in the film to be increasingly relevant. When Armour was writing his book, tensions around civil rights for Black Americans, desegregation, and police brutality against Blacks were prevalent in public discourse—a national conversation that continues to inform social anxieties and conversations around police brutality against people of color via social media and popular news platforms today. However, before analyzing the cultural politics of the #BlackLivesMatter (#BLM) movement in more detail, we must first address the history of lynching as well as its contemporary resonance in the United States.

Lynching in America

The term “lynching” continues to have racial connotations today. The Emmett Till Antilynching Act, a bill that will make lynching a hate crime on the federal level, was introduced on January 3, 2019 and passed in the House of Representatives on February 26, 2020 with 410 votes in support and just 4 votes in opposition.25 However, lynching is not used in Fury to depict White-on-Black crime, but rather White-on-White crime. This calls for a closer look at its etymology and how the term was used during the 1930s, as Fury was being released to American theaters.

Monroe Work Today, an organization dedicated to the education and documentation of lynching in American history, clarifies that the term has undergone multiple iterations in its evolution. The organization explains that lynching refers to events of mobs taking their victim(s), accused of some sort of crime, to publicly execute them.26 This procedure is occasionally coupled with torturing the victim for the amusement of the mob-participants.27 American historian Robert W. Thurston argues that social crisis lies at the core of mob murder: “When lynchers have captured and killed prisoners, on no few occasions removing them from jails or law enforcement officials, a severe problem in perceptions of legitimacy has been at work.”28 Falling under what Thurston categorizes as transitional lynching,29 he clarifies that “[w]hen the government’s legitimacy is suddenly questioned, it seems that people fall back on local, known groups, but also that those groups become more violent as they grope for ways to reestablish order and control crime.”30 Lang’s use of the term lynching, then, accurately describes what would have transpired had the mob’s intention to murder Joe inside of the jail been realized.

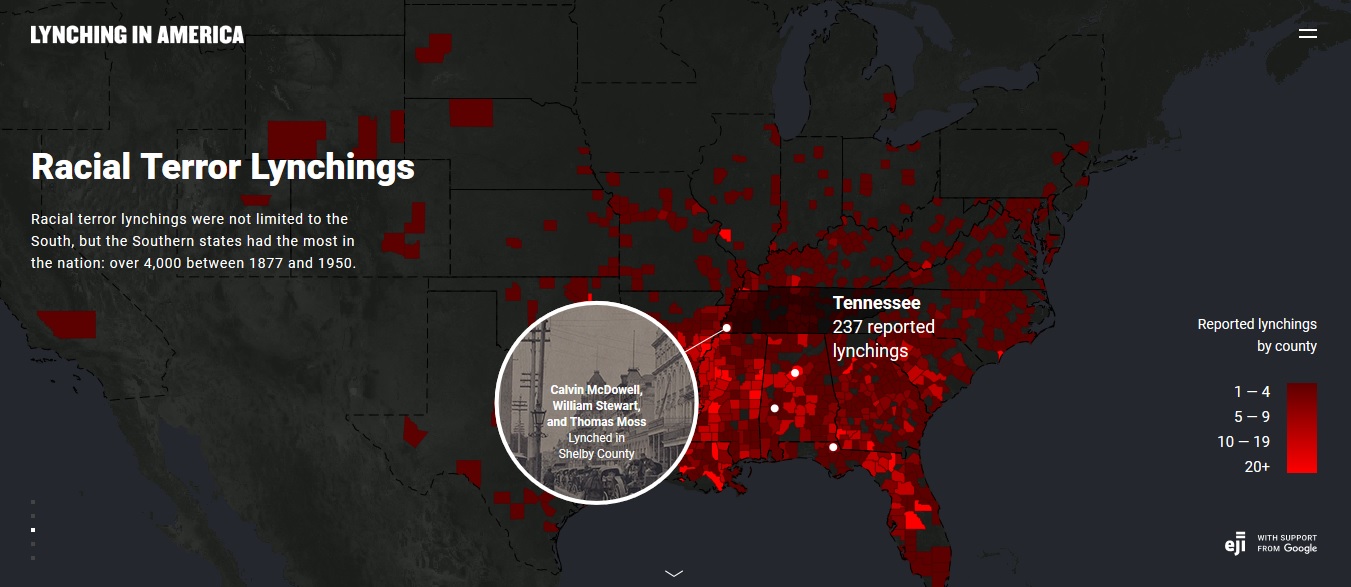

But what was socially invested in the term “lynching” at the time of Fury’s release? According to the Equal Justice Initiative,31 over 4,300 lynchings of African Americans took place in the United States between 1877 and 1950.32 When the term is quantified in Fury, the prosecuting district attorney states that, up to that point, 6,010 people had been lynched in the United States with only 765 of these cases being brought to trial.33 As a point of comparison to the numbers used in the film, from 1880 to 1930, 2,800 African Americans were lynched while some 300 Caucasians were faced with the same tragic circumstances.34 This means that there was a roughly 9:1 ratio of Black-to-White lynchings in America just prior to the release of Lang’s film. These figures provide some context as to why the term became racialized in the US. This is more overtly expressed in Fury through the reaction of the shoe-shine who jumps in fear upon the outbreak of the mob headed for its unknowing victim. And Fury was not alone in thematizing lynchings in Hollywood in the early twentieth century. Robert Jackson looks at the extensive and oftentimes confusing and misunderstood history of lynching films and comments on the predecessors of Fury including D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), Oscar Micheaux’s Within Our Gates (1920), and Victor Fleming’s The Virginian (1929).35 Fury therefore participated in a larger conversation taking place in Hollywood, which Jackson sorts into pro- and anti-lynching categories. Moviegoers were already culturally primed for the subject of lynching to be placed on screen prior to Fury’s release. Lang’s film especially excels in showing that particular developments must take place for a lynching to be carried out. Mob mentality and perceptions of vigilante justice are precursors to potentially deadly ends.

Figure 2: “Lynching in America” Interactive Map from the Equal Justice Initiative Website. Source: “Racial Terror Lynchings,” Lynching in America, available at: https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/explore/.

Source: “Racial Terror Lynchings,” Lynching in America, available at: https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/explore/.

Mob Mentality and Vigilante Justice

Lang thematized mob mentality and vigilante justice in several of his German films leading up to his emigration to the United States. Like the attempted lynching in Fury, Lang’s M features a mob of criminals assembling in a kangaroo court to try to convict a child murderer in an attempt to uphold the law and social order.36 Also, Lang’s most successful film, Metropolis, features uncontrollable mobs as an evil robot, that takes the likeness of the hero’s love interest, wreaks havoc on the city. Clarifying the difference between lynching and mob behavior in an interview for the New York Times, Lang stated that “Fury is a story of mob action […] Lynching happened to be the result.”37 Yet, the mob action can only remain anonymous as long as cooperation takes place among everyone involved; in Fury, this is a task faced by the entire community of Strand.

The violence that ensues at the hands of the mob in Fury has only one tactic available if the members of Strand want to see this incident go away with no one convicted: each member of the town must cooperate in order to provide alibis and deny participation in and/or knowledge of those who comprised the vigilante mob on that particular night. The Monroe Work Today organization asserts that a mob’s behavior during a lynching points to their belief that they are justified, leaving no individual singled out for the possibility of persecution.38 Those involved in the mob in Fury also conform to this mentality. Even the police officers who acted in defense of Joe at the jail end up lying under oath. Nevertheless, this tactic fails as Katherine, an outsider to the community, testifies and confirms to having seen Joe trapped in the jail. Katherine’s testimony is the key element that Joe and his brothers, Charlie and Tom, need for winning the case and convicting the twenty-two defendants for murder. Katherine is a bystander and a witness to the attempted lynching and therefore foils the Strand community’s compact of solidarity through silence. Complementing Katherine’s testimony is the newsreel-as-filmic evidence, which the prosecution presents to identify the defendants’ individual members as participants in the violent mob.

Introduction of Filmic Evidence in a Courtroom Setting

Lang’s Fury presents filmic evidence in the conviction of a crime by using it as a tool for identifying mob participants. The district attorney is hired by Joe’s brothers and presents the court with a newsreel that was supposedly recorded while the mob attacked the jail. This is presumably possible as Fury previously depicts men recording the event from a balcony, in addition to a caravan of news reporters that pass Katherine at a gas station, raising her suspicion of Joe’s imminent danger. Film scholar Reynold Humphries comments on this scene, noting the role of the news cycle and how news outlets go about reporting their stories. Humphries states that “[a]s soon as the story gets around that something is happening in the town, people start flocking there, which leads a bus driver to say: ‘These newsreel men are on their toes. They must have found out about this before it happened.’”39 Humphries argues that Lang deftly maneuvers through this situation as a critique on how news stories are often fabricated, regardless of the medium.40 Humphries strengthens his argument by examining the only scene in Fury that depicts a newsreel in the process of being recorded: in the scene in question, the spectator is shown a series of cameras which are positioned off of the balcony of a hotel room that is presumably in view of the jail and the subsequent mob violence.

Figure 3: The screen for Presenting the Newsreel in the Courtroom and the Vantage Point of the Cameraman on the Balcony. Source: Fritz Lang, Fury, 1936.

Source: Fritz Lang, Fury, 1936.

However, the position of these cameramen does not line up with the vantage points previously offered to the spectator when viewing the mob in action, leaving audiences skeptical as to what is presented as evidence in the courtroom. As they witness the events that lead up to the mob attempting to burn Joe alive, the audience is given multiple vantage points, making the identification of many of the defendants easy to connect. Yet, the images shown in the newsreel evidence are not previously seen by the spectator of Fury. The perspective remains anonymous, leaving doubt as to where the footage came from and whether that source should be considered reliable. This doubt should be significant for the spectator because it throws an additional, unknown viewer into the film’s narrative. It also points to a general skepticism associated with the moving image and whether sequential moments captured on film can serve as trustworthy representations of what happened when they were recorded.

Doubt over Filmic Evidence in Fury

In Fury the newsreel serves as the district attorney’s secret weapon for breaking the collective silence of the twenty-two members of mob who are standing trial. The district attorney requests permission from the judge to screen the newsreel: he plans to identify a selection of the defendants, thereby revealing perjury on the side of both those on trial and the citizens who provided alibis under oath. As mentioned above, the inclusion of newsreel as evidence was not as commonplace in the 1930s as it is today. Historian Norman Rosenberg comments on the value of filmed media in the courtroom, writing:

Fury posits newsreel footage as thoroughly empirical evidence. Though problematic in terms of verisimilitude—this kind of photographic proof would have likely been inadmissible in any courtroom in 1936—this narrative turn is crucial to the film’s complex legal logic. In contrast to testimony of what people merely claimed to have seen, Fury ironically offers the camera’s “objective” eye as omnipotent and all-seeing.41

Through its presentation as all-seeing, the newsreel points to a problem: We do not definitively know where this footage came from.42 German scholar Theodore F. Rippey explores this conundrum by using the audience viewing the newsreel in the courtroom to identify the same situation for the spectators of Fury. The district attorney uses the newsreel to present what he refers to as “stop-action,” or freeze-frames, in order to identify one of the men on trial. As he does, his wife rises from the gallery of the courtroom and yells out, “No, it’s not true!”43 Rippey confirms her exclamation by saying,

she is technically correct, though she herself does not know it. The casual observer is likely duped: no one in the courtroom (and only the rare spectator) notices the discrepancies. The fingerprints the images bear, therefore, are those of the omniscient artist.44

The woman’s outcry in the courtroom reveals both her disbelief in her husband’s alleged behavior presented on screen, while also calling the spectator to question the validity of the source providing this information. The spectator knows that her husband was present at the jail as the mob was carrying out their deadly plan. The spectator also knows that the freeze-frame selected by the district attorney presents a moment not previously seen on screen. Rippey clarifies that “[t]hese images indeed reveal new narrative and visual details, but if we scrutinize them closely enough, we also discover that they are, in at least one sense, bogus.”45 What Lang therefore presents to the audience is a two-fold commentary on how filmic evidence can (or perhaps should) be consumed. On the one hand, Lang offers the clear advantage of identifying participants present at a given event and their behaviors in a contained medium that can be revisited time and again. On the other, Lang warns against accepting what is presented on screen as irrefutable truth. Like the movie screen of Fury, all the spectator can discern from filmic evidence is what takes place in front of the lens. Problematizing even this statement is the presence of cuts in newsreel footage, much like what is presented in the courtroom. Filmed narratives that feature cuts present a curated version of any events captured, thus merging the evidentiary offerings that filmed events are able to provide with clear limitations to how they are perceived.

In challenging what Rosenberg identifies as an all-seeing eye, we cannot put much stock in what this omnipresent perspective offers us in terms of ascertaining the truth. However, scholars have read Lang’s inclusion of the newsreel as holding contradictory significance. Presenting the multiple interpretations of scholars who have engaged in this discourse, Rippey considers the readings of film scholars Anton Kaes, Tom Gunning, and Thomas Elsaesser as exemplifying the range of commentary and/or critiques presented by Lang through his presentation of justice in Fury. Kaes reads the newsreel as an idealist desire held by Lang for the medium of film to serve as undeniable proof, making it a viable option to later condemn the Nazis of their crimes.46 Gunning interprets the newsreel through the scope of surveillance and its manipulability,47 and Elsaesser reads its inclusion in Fury as a warning by Lang for the medium to not be used as proof.48 Zooming-out from the film, film and media scholar Stella Bruzzi says outright that “[t]he judicial system, in the cinema of Fritz Lang, is not to be trusted. Instead, it is revealed as ineffectual, wayward and capricious; invested with considerable authority, it actually possesses very little.”49 Like the skepticism and general wariness communicated by Gunning, Elsaesser, and Bruzzi, the doubt that comes with the moving image is still observable in not only the contemporary courtroom but also in general society.

Scholars like Rippey, Kaes, Gunning, Elsaesser, and Bruzzi illuminate the breadth of interpretive investment in the newsreel as evidence presented in Fury. Yet, to return to Eisner, she reads the inclusion of filmic evidence in Fury as an example of Lang anticipating a practice that would soon become commonplace in court trials.50 Breaking down the significance hidden in how Lang employs the newsreel in this scene, Humphries offers his interpretation of the director’s commentary by identifying not only what Eisner gets right, but also what she has overlooked. Humphries states, “[t]his historical reminder is there to show us Lang’s intuitive genius, how much in advance of his time he was. So far, so good, except for one little detail: twenty-two people in the film are condemned to death on the strength of newsreel footage for a crime that never took place.”51 Therefore, the ‘truth’ the footage presents is no Truth at all. It leads its spectator to believe that Joe perished in the jail without providing any evidence as such. Humphries comments on this deception and how the defense lawyers are the only ones who remain wise to this flaw. Regarding the lawyer’s strategy, Humphries argues that,

were an eyewitness to swear to have seen Joe, then one could say Joe was in the prison and therefore that the accused are indeed guilty. The importance of Fury’s use of the newsreel lies in the way it sweeps aside such a line of argument.52

Had the newsreel shown Joe in the jail, the prosecution would have won a case of murder largely due to the filmic evidence.53 Alternatively, if a citizen of Strand admitted to having seen Joe behind bars, Katherine’s testimony would not have been doubted, also leading to the conviction of the twenty-two defendants.54

Humphries further details how the line between newsreel and the cinematic experience of Fury fade in this moment as the newsreel is screened in the courtroom. He comments:

We, the subjects of the enunciation, relive that night in the same way as the people in the courtroom, for the simple reason that the cinema screen brought into the court fills exactly the cinema screen we are watching, that of Fury itself.55

Thus, the spectator is left to assign no more trust in the newsreel than in Fury as a cinematic experience itself. Using freeze-frames, the district attorney creates snap-shots, or cinematic photographs, of isolated moments experienced during the attack on the jail. I read this oscillation between still and moving images as Lang emphasizing how extracting moments of action out of context and assigning meaning to them, despite one’s best intentions, results in walking a thin line between what constitutes the truth and what is only an illusion of truth.56 The newsreel aids in the identification of twenty-two people who were found guilty of and therefore sentenced for having committed first-degree murder, all without having actually committed the crime. While Fury concludes with a resolution of Joe admitting his plot for revenge, we are left with the fact that he was able to accomplish his goal of having the twenty-two defendants condemned to death via a legal trial, thereby sentencing them to what he calls “legal death.” The problem lies in the validity of the footage: a conundrum presented first by Fury, we continue to see this struggle present in American society and culture today, yet brought to new light through the #BLM movement.

Figure 4: The Freeze-Frame Provided by the Defense Attorney that Fits the Screen of Fury with a Still of the Gallery Scene. Source: Fritz Lang, Fury, 1936.

Source: Fritz Lang, Fury, 1936.

Lang’s Fury and the #BlackLivesMatter Movement

The history of lynching in America reaches back to the country’s very foundations, and the practice was still considered common at the time that Fury was released. One of the most famous cases in this history was the lynching of fourteen-year-old Emmett Till in Mississippi in 1955. This crime was only resolved six decades later when his accuser, Carolyn Bryant Donham, admitted to lying about her allegations against him in 2017.57 Contemporary examples of lynchings are often seen as having evolved out of the historical approach of mobs hunting down and creating spectacles out of often innocent Blacks that ultimately lead to their deaths. Today, while traditional lynching still does take place (albeit rarely), social discourse is centered around its systemic manifestation through interactions between people of color, predominantly African Americans, and law enforcement. Articles published during the summer of 2020 called for attention to be paid to “modern-day lynchings” that take the shape of Black Americans dying at the hands of police.58 Consequently, in 2016, the United Nations (UN) Working Group of Experts on People of African Decent presented a report that was debated at the UN Human Rights Council. The report compared the violence “between modern police behavior and mob killings of Blacks in the 19th and 20th centuries.”59 Contemporary conversations around police interactions with Black America and the unnecessary deaths of African Americans at the hands of police officers therefore fuel my re-reading of Lang’s Fury as a film that resonates in this current chapter of American history that has seen the birth of the #BLM movement.

#BLM initially began as a social and political movement in the wake of the murder of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman in Sanford, Florida in 2012. The #BLM organization—founded by three African American women: Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi, and Patrisse Cullors60—defines itself as “an ideological and political intervention in a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise. It is an affirmation of Black folks’ contributions to this society, our humanity, and our resilience in the face of deadly oppression.”61 The #BLM organization and movement have continued to protest the numerous examples of shootings and general mistreatment of African Americans by law enforcement.62 The ever-growing list includes the high-profile cases of Michael Brown, Jr. in Ferguson, Missouri and Eric Garner in Staten Island, NY in 2014; Jamar Clark in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 2015; Philando Castile in St. Anthony, Minnesota in 2016, among numerous others.

However, not every interaction with the police that has drawn the attention of the #BLM community has involved shootings. Incidences of police officers using excessive force have also resulted in demonstrations and a call for change in how police are trained to interact with communities of color. Dajerria Becton, who attended a pool party in McKinney, Texas in 2015 and was slammed to the ground by a police officer, recently won a settlement worth over $100,000.63 She was fifteen-years-old at the time of the incident when former police officer Eric Casebolt was captured on camera aggressively restraining her. Sandra Bland is another example that made headlines in 2015, when she was pulled over for a traffic stop that led to an altercation and subsequently to her death in police custody a few days later. The release of video footage found on Bland’s cellphone in May of 2019 led to calls to reopen her case.64 One of the most socially mobilizing acts of police brutality in 2020 was the murder of George Floyd by police officer Derek Chauvin in Minneapolis, Minnesota on May 25. Cellphone footage recorded and circulated by witnesses capturing the eight minutes of Chauvin kneeling on Floyd’s neck breathed new life into the #BLM movement.65 In March 2020, the demand for justice for the murder of Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky and awareness of mistreatment of and violence against Black and Brown trans lives, such as that of Tony McDade in Tallahassee, Florida in May, made waves both across social media and in the streets across the nation.66 All of these incidents involved African Americans, police misconduct, and recorded video footage of the respective incidents. While the #BLM community has fought against the continued normalization of police misconduct against people of color for nearly a decade now, the importance of capturing encounters with the police on cell phone video has brought the phrase “seeing is believing” under new scrutiny.

As presented by Lang, seeing is no longer believing when the medium of the moving image is at play, but rather, to see is to be skeptical. While film and live action recording is often perceived as the best option for capturing sequential moments in time, the fact that it also lends itself to manipulation and modification forces its audience to doubt its reliability. Lang presents this problem through screen-fitting the newsreel with that of the entire screen of Fury, calling for the spectator to equate the reliability of the two cinematic inputs. It is obvious that the narrative of Lang’s film is fictionalized,67 yet the audience is not fooled into thinking that what they see on screen is a depiction of truth within the narrative. Through the newsreel, the audience in the courtroom and the spectator of Fury are both led to believe that the members of the mob successfully lynched Joe by destroying fire hoses and throwing torches into the jail—yet much is left unseen. This issue of the unseen that falls outside the scope of the lens continues to present challenges today. The struggle that is coupled with the moving image is the attempt to piece together fragments of truth, often collected and reassembled after the event concludes, to deliver minimally tampered-with, unbiased evidence of what happened at any given event. As Fury presents both sides of this coin of truth, we must not be too quick to dismiss the clear advantages that nonfiction footage offers in evidentiary power and potential.

The role of nonfictional media and how they gain access to the truth is embedded within the fictional plot of Fury and presented through both newspaper and newsreel in the film. But it is the role of the newsreel that is, historically, most directly tied to evidentiary power. In merging a nonfictional medium with a fictional production, Lang shows how nonfictional media, regardless of their format, have the distinct potential to unravel fabrication. In his investigation of documentary film, Philip Rosen refers to the 1933 Oxford English Dictionary definition of the term document and its dual meaning: “One of these interrelated semantic clusters has to do with teaching and/or warning, and the other with evidence or proof.”68 Lang’s Fury presents both definitions through the use of the newsreel as a nonfiction filmed document. The newsreel can be (and is often) read by scholars as an attempted warning to the spectator when it comes to questions of reliability due to the inconsistencies of the filmmakers themselves and the perspective of the newsreel in the courtroom. But the newsreel also efficiently serves as evidence to prove which members of Strand were indeed present at Joe’s attempted lynching. After all, if the trial was for attempted murder and Joe had revealed his survival, then the defendants would have been legally convicted for that crime. In commenting on the merging of Hollywood productions with that of nonfiction, Rosen says, “both Hollywood film and the documentary tradition, in their insistence on craft, skill, and sequence—in short on aesthetics and meaning—provide a function for a specialized elite in the imposition of significance for the spectator by means of the configuration and organization of documents.”69 When it comes to the origins of documentary film, Rosen details how the founding developments of what he calls “classical fiction film” and “entertainment filmmaking” that evolved between 1908 and 1917 were placed in contrast with nonfictional productions.70 He comments on the unproduced capture of reality and that “the appeal of many actualities was in the relatively extreme rawness of the real they present, which is ultimately to say that they do not seem overtly planned or reorganized to fit into an intratextual sequence.”71 Rosen singles out journalism as falling within this category, which we witness in Fury through the format of the newsreel.72 By embedding nonfictional documentation in the plot, Lang includes the social power of nonfiction media and how they can serve as proof of what has happened at a specific point in time, at least to the extent of what is seen in front of the camera lens. In exemplifying the evidentiary capacity of nonfictional film within the narrative of Fury, we see a clear foundation for the role of nonfiction film and its power in providing proof that is still observable in cases of social justice today.

When translated outside of Fury and into contemporary social politics, the benefit of the doubt and faith in accuracy of what is captured through film quickly dissipates through mass media circulation. As filmed content is circulated, it is more susceptible to being manipulated, leaving narratives often fragmented. Attempting to deter this from happening on the side of law enforcement, the federal government has provided opportunities to aid in updating law enforcement agencies in the purchasing of body cameras.73 However, there are currently only two states that require body cameras for law enforcement officers: Nevada and South Carolina. My intention here is to tease out the problem of doubt that accompanies filmed evidence, regardless of its source. Lang predicts this issue in the way that he incorporates filmed evidence in Fury. In accordance with the changes in policing practices to provide reliable filmed accounts of encounters, other policies have been implemented that potentially incriminate eyewitnesses when video recording interactions with the police.

Filmic Evidence in Contemporary Attempts to Capture “Truth”

In the United States, laws pertaining to the video recording of interactions and events vary from state to state. While there is no federal law that holistically declares the video recording of the police to be a right of the people, there is also no law declaring it illegal per se. In fact, in response to the increase of documented police cases using excessive force, more and more journal articles have been published addressing the laws and parameters under which one is protected when filming incidents between law enforcement and members of the public. Lawyer Raoul Shah, for instance, has published on police misconduct and the rights of civilians to record law enforcement. Shah not only draws parallels between the laws surrounding wiretaps, which have historically been used to defend police in cases in which they were filmed,74 but also how the First and Fourteenth Amendments can be interpreted as extending to include the use of film as a medium.75

The First Amendment states, “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.”76 In reflection of the prominence of hand-held recording devices among the American populace, the law has been successfully extended and applied in court cases to reach beyond referring solely to the press, but rather also to the general public as well.77 Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind that this right protects those who are in public spaces and are not posing a threat to the police or impeding them from their job. If the police are put in danger, are threatened, or if the investigation is in any way compromised by being video recorded by a civilian, the protection of the First Amendment no longer applies.78

When partnered with the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment, the right to record the police can be well-protected, so long as no statutes have been passed decreeing otherwise. Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment declares,

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.79

However, different Circuit Courts have made opposing rulings for cases that are similar in nature, leaving distinctive lines unclear as to what is legal and what is illegal in any particular state.80 Yet, Americans are starting to make sure that they can protect themselves under these two amendments—a freedom which has come at a social cost to some who have chosen to exercise it.

Kevin Moore, the man who recorded the shooting of Freddie Gray on April 12, 2015, has brought awareness to some of the potential ramifications of recording the police. In an interview with Dragana Kaurin for VICE magazine, Moore comments on how his recording of the shooting of Gray led to “months of police harassment, intimidation, doxing, and a false arrest after filming the Freddie Gray video.”81 Kaurin also interviewed other civilians who recorded events that fueled the #BLM movement in the following years. Kaurin states,

While their videos have sparked protests and community action, people behind other high-profile videos of police killings of Eric Garner, Walter Scott, Philando Castile, and Alton Sterling have also alleged retaliation from police for filming them. Like Moore, each of them told me stories of false arrests, intimidation, physical violence, doxxing [sic], and illegal confiscation of their phones after filming or sharing videos of police misconduct.82

Ramsey Orta, who captured and circulated one of the videos of Eric Garner’s death, also experienced backlash after recording the encounter. Chloé Cooper Jones writes that upon arrival of the police to Orta’s home the night of Garner’s death, Orta thought, “[t]hey’re here for me … because I have proof of what happened.”83 What Orta did not anticipate was that, as Cooper Jones states, “the cops would exact their revenge through a campaign of targeted harassment, that within a year [Orta would] be in prison and facing constant abuse, his enduring punishment for daring to hold the police accountable.”84 In her article, Cooper Jones reports on why Orta had initially started habitually recording interactions with the police, considering it “a form of self-defense.”85 Documentaries like Whose Streets, which features interviews with prominent protesters and footage of the tensions following Michael Brown, Jr.’s murder, are pointedly invested in “cop watching” as a method of protecting oneself and the truth of how law enforcement engages with the Black community. Protester and cop watcher David Whitt states, “[y]ou know, don’t give them an opportunity to gun somebody down in the street. Be out there to watch ‘em [sic]. I don’t go out with no weapons or nothing like that. I go out with my camera. That’s my weapon, you know, and the fact is that since the police are not being held accountable, we have to hold them accountable.”86

This mindset of self-defense through recording has spread within communities of color and with it there has been a push for technology to keep up. Recent developments in smartphone apps like Mobile Justice, created by the American Civil Liberties Union, and Cop Watch Video Recorder are designed for civilians and reflect a growing desire to record encounters with the police.87 Cop watching, the action of recording police with the purpose of capturing police officers overreaching their positions of power, places a comparable power in film as a weapon to keep acts of misconduct in check. As social attention continues to be paid to the ways in which police officers interact with people of color, these same demographics feel the need to better protect themselves by way of video-recording interactions with law enforcement should these various encounters escalate to violence. Some have completely forgone with trying to merely record encounters but have instead begun live-streaming them to social media platforms like Facebook or apps like Witness. Diamond Reynolds took this option when she, Philando Castile, and their daughter were pulled over by the police. Witness developers identify their contribution to the changes in social discourse and the role of filmic evidence within it as

work[ing] to ensure the media, policy and technology landscapes allow video to realize its full potential as a human rights tool. In a world where an unprecedented number of people are becoming citizen witnesses, we believe technology companies should recognize their needs.88

In sum, citizens are attracted to technology to help protect human rights while also holding perpetrators of violence and those who remain silent accountable. Significantly, this attraction illuminates a general social skepticism and/or loss of trust in law enforcement that has been recorded in surveys across America. Concomitantly, the doubt and suspicion that people of color face when reporting acts of injustice from law enforcement motivates these same demographics to press the “record” button on their phones. Filmic evidence then serves as an attempt to prove validity to civilian reports of misconduct by the police while simultaneously trying to preserve the “truth” of how those same events transpire.

In correlation with the perceived need to safeguard oneself and the truth of what happens during interactions between civilians and law enforcement, results from the 2017 Gallup survey show that the average rating of confidence in the police has recently returned to its twenty-five-year average of 57%.89 Meaning that in 2017, 57% of American reported as having “‘a great deal’ or ‘quite a lot’ of confidence in the police.”90 In 2015, the confidence level in police hit a record low of 52%, which Doug Criss of CNN states was “during the initial rise of Black Lives Matter, when a series of deadly police encounters with unarmed Black men led to months of protests.”91 Yet in the 2017 report, the confidence rating has continued to drop among Blacks. From the 35% confidence in the police in 2015, Blacks reported a dip down to 30% in the 2017 report.92 Liberals also experienced a significant fall from 51% in 2015 to 39% in 2017.93 And, the age group of Americans between 18-34 years showed a 12% drop from reporting 56% confidence in 2015 to just 44% in 2017.94 Beyond news stories that have gone viral about police shootings, other corners of popular culture have taken up the topic as well.95 How the moving image is being employed to capture encounters and mobilize conversations around social tensions pertaining to race appears to be manifold. In the summer of 2016, Vox’s German Lopez comments on a reason behind this dip in confidence since 2015, writing that “[t]he proliferation of video through smartphones, dashboard cameras, and body cameras—and social media’s ability to send a video into viral overdrive—has played a major role in holding police accountable, especially this year.”96 As Lopez looks back on the fluctuating reputation of the police in American history, he starts with the famous Rodney King incident that placed the racist and violent history of police against people of color—in this case a black man—in the forefront of American social and political discourse.

A year after Lopez’s article was published, National Public Radio commemorated the twenty-five anniversary of the Rodney King trial with an article detailing the events of that fateful night. Authors Anjuli Sastry and Karen Grigsby Bathes summarized the incident between King and the Los Angeles police officers as well as the instances of social unrest which immediately followed. Commenting on the video footage of King being kicked and beaten with batons for fifteen minutes, criminal justice and law professor Jody David Armour is quoted as saying, “[t]here was ocular proof of what happened. It seemed compelling … And yet, we saw a verdict that told us we couldn’t trust our lying eyes. That what we thought was open and shut was really ‘a reasonable expression of police control’ toward a black motorist.”97 In a case of excessive use of force by law enforcement, the footage of the 1991 incident served to capture two important pieces of information: law enforcement can show excessive and potentially deadly use of force without legal repercussions and video footage of such events are received with scrutiny and doubt in their validity. The former is something we witness regularly through contemporary uses of social media. The latter was foreseen and exemplified in Lang’s Fury and continues to incite social outrage as examples of police brutality continue to pile up without their perpetrators being brought to justice. And conversations pertaining to the role and necessity of police surged again in the summer of 2020 as calls for defunding law enforcement agencies circulated across the nation.98 We see a growing embrace of recording events that may potentially be used as evidence in court, just as Fury prophesied. We however also see that the complexity around the legality, availability and perceived need for such technology shows that the medium continually generates debate around its reliability and accuracy in capturing moments which often rely heavily on context.

Conclusion: Ongoing Fury Today

By introducing the moving image as potentially worthy of great evidentiary value in a courtroom, Lang succeeds at simultaneously justifying and condemning the medium in its presentation of proof. Fury hints at the tension around race through the themes of lynching and the pursuit of justice that we continue to see debated in contemporary social justice struggles around the #BLM movement. While Joe was successful at legally condemning those twenty-two mob members through the assistance of the medium of film, he confesses to the truth, sparing the lives of those who had tried to lynch him. Historian Russell Rickford speaks on the evolutionary timeline of endeavors in racial equality in America:

Of course, determination to preserve black life in the face of white supremacist violence has always been a radical principle, from the anti-lynching crusades of Ida B. Wells around the turn of the twentieth century, to the Negro Silent Protest Parade of 1917, to the protests surrounding the Scottsboro Boys case of the 1930s, to the 1951 We Charge Genocide petition by the Civil Rights Congress, to the exertions of the Deacons for Defense and the Black Panthers at the peak of the postwar movement. What animated these struggles—and those of countless leftist and labor causes—was their insurgent nature and the uncompromising character of their rank and file participants, traits that Black Lives Matter exemplifies.99

In her book Black Lives Matter: From a Moment to a Movement, Laurie Collier Hillstrom comments on the primary role of social media in how evidence in the formats of videos, photographs, and narratives of injustice are disseminated and awarded value. She stresses that “[i]n many cases, their raw footage and commentary directly contradicted the accounts of events offered by law enforcement officials or mainstream news media.”100 The social move toward using filmed moments as proof appears to be here to stay until a medium that proves to be more reliable is deemed a more attractive option. Hillstrom also describes how retaliation, like that experienced by Moore and Orta mentioned above, tends to stick to the medium of film. These retaliation videos function as social ammunition when they are circulated in opposition to one another in an attempt to discredit the message(s) of their predecessors.101 Unfortunately, it remains rare for the perpetrators in situations where people of color are victims of excessive force to be convicted of their crimes; more often, they are acquitted in court for their violent and/or deadly actions.

The disciplinary hearing of Garner’s killer, officer Pantaleo, resulted in Attorney General William P. Barr ordering the case to be dropped in the summer of 2019.102 Officer Pantaleo’s punishment was delivered on August 19, 2019 and took shape in his termination from the New York City Police Department.103 In anticipation of the verdict of what would happen to Garner’s killer, many felt as though the disciplinary hearing would serve as yet another example of a failed justice system.104 Tensions around police brutality saw a resurgence following the deaths of Taylor in March 2020 and Floyd just two months later. While footage from the night of Taylor’s death was not released until July of 2020,105 recordings of Floyd’s murder quickly circulated on social media platforms the day of the event, instigating widespread social unrest in addition to international and nationwide protests. The direct impact of the adoption of video recording police has greatly changed the way civilians disseminate information, communicate online through social media,106 and make cases against unlawful behavior by the police. The frustration that accompanies this medium—which is both trusted and doubted—leaves oppressed groups scrounging for other modes of relaying the atrocities that have historically gone over-looked and under-addressed throughout American history. Yet, the medium of film and the capabilities it offers regarding proof of injustice and the circulation of information across the globe offer clear and impactful strengths to its regular adoption. Back in the 1930s, Lang successfully invested Fury with a timelessness tied to race in America that directly addresses the frustration that comes with filmic evidence. By thematizing lynching in correlation with the presentation of skepticism in the medium of the moving image, Lang critiques a judicial system that has significant flaws, but did so in a way that experimented with new endeavors to relay truths deemed unreliable. However, like many of the officers who have ended the lives of unarmed African Americans, we must not forget that the actions of the mob in Fury were also left unpunished as the film concluded.107 While those on trial were spared the guilty verdicts that were sentenced prior to Joe’s reveal as having survived the attempted lynching, Fury ends without resolution as to what happens to those same mob members who were indeed guilty of attempted murder.

Filmic evidence, while not perfect, is presented in Fury as a stepping-stone toward society-wide accountability. Had the citizens of Strand named the members of the mob and redeemed themselves as a civilized community that holds itself accountable for its actions, as Joe does at the film’s conclusion, Fury would have ended a very different story. Instead, we are quick to blame Joe, the initial victim in this narrative, for struggling to come to terms with a shattered world view. As he says at the end of Fury, a part of Joe died in the fire—he lost his perception of truth in the world, which was tied to his belief in justice and the idea that men are civilized. But at its most basic level, Joe lost his sense of pride in his country.108 The never-ending pursuit of truth, for the sake of holding others accountable who cannot be relied on to do it themselves, is the shock experienced by Joe in Fury and a shock that continues to be experienced in America today.

Every event of injustice, examined here through the scope of racial inequality, calls us to address more than the flaws in our judicial system. We know they exist. Instead, Lang and his contemporaries invite us to address the injustices that we propagate against other human beings, calling to hold ourselves accountable by confessing to our transgressions, naming our biases, and reflecting on our actions before we initiate them. When juxtaposed with contemporary films and digital media, we see the conversation that originated during the Civil Rights Movement continues to be revisited today.109 Mob psychology, linked to times of crisis and social instability, often takes shape as a regression out of the status of being a civilized society. Attempting to redeem the twenty-two members of Strand, Katherine states, “[t]hey were part of a mob. A mob doesn’t think. It hasn’t time to think.”110 But the problem with humanity, as presented by Fury, comes after the mob disperses and those involved begin to reflect on their actions. Commenting on why so many instances of lynching never go to trial, the district attorney states that it is “because their supposedly civilized communities have refused to identify them for trial. Thus, becoming as responsible, before God at any rate, as the lynchers themselves.”111 The members of the mob are therefore not the only ones at fault, but blame must also be passed onto the broader society in which the mob was formed.

Today, video is used as a tool to encourage, or perhaps demand, self-reflection. Filming the police in events of misconduct calls for the perpetrators to be held accountable for their actions. Furthermore, the circulation of these filmed events calls for society at large to hold itself accountable for the systems that have oppressed and neglected the truth presented by people of color when placed in opposition to voices in positions of power. Fury scrutinizes filmed evidence by presenting its strengths and weaknesses regarding reliability and the role of doubt. As society continues to grapple with these same struggles, filmic evidence serves to validate the voices of the oppressed by offering the opportunity for reliving the moments in question. Through his first American film, Lang critiques a society that would rather remain silent in solidarity than speak up and grow and develop as a civilized public. The #BLM movement continues to vocalize this call for change—a call for America to document, to share, and to #SayTheirNames. In times when inaction and silence are interpreted as compliance, the #BLM movement continues to strive for justice, because without justice there is no peace.

Notes

- Chloé Cooper Jones, “He Filmed the Killing of Eric Garner—and the Police Punished Him for It,” The Verge, 13 Mar. 2019, https://www.theverge.com/2019/3/13/18253848/eric-garner-footage-ramsey-orta-police-brutality-killing-safety.

- For more on the rules, congressional hearings, and attempted remedies for excessive force at the hands of law enforcement and how it is prohibited under the Fourth Amendment, see Richard M. Thompson II, “Police Use of Force: Rules, Remedies, and Reforms,” University of North Texas Libraries, UNT Digital Library, Washington D.C., report, 30 Oct. 2015, pp. 1-26, https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44256.pdf.

- Ashley Southall, “‘I Can’t Breathe’: 5 Years After Eric Garner’s Death, an Officer Faces Trial,” The New York Times, 13 May 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/12/nyregion/eric-garner-death-daniel-pantaleo-chokehold.html.

- “Herstory,” Black Lives Matter, https://www.blacklivesmatter.com/about/herstory/.

- IBW21, “Harvard University Sued Over Earliest Photos of American Slaves,” Institute of the Black World 21st Century, 22 Mar. 2019, https://www.ibw21.org/reparations/harvard-university-sued-over-earliest-photos-of-american-slaves/.

- Lotte Eisner, Fritz Lang, Oxford University Press, New York 1977, pp. 161-162. Eisner comments on the uncertainty around who exactly, Lang or Cormack, decided to incorporate newsreel as filmic evidence in the plot. Eisner states, “It is impossible today to disentangle Lang’s contribution from that of Bartlett Cormack, to the script that bears both their names, though we know that at that time Lang’s English was far from perfect. For his own part he is too modest to lay claim to individual passages, though such an idea as the use of the newsreel film in a court to lead to the conviction is very characteristic of his approach.”

- Gene D. Phillips, Exiles in Hollywood: Major European Film Directors in America, Lehigh University Press, Bethlehem, PA. 1998, p. 37.

- Patrick McGilligan, Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis 2013, p. 223.

- Phillips, Exiles in Hollywood, p. 37.

- McGilligan, Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast, p. 220.

- Eisner, Fritz Lang, p. 164.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. p. 164; pp. 166-167. Eisner discusses some of the scenes that were eliminated from the screened version of Fury, two of which she states included minor Black characters.

- McGilligan, “1934–1936” in Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast, pp. 207-39, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1997, p. 221.

- Another nod to racialized commentary observable in this sequence is of a member of the mob snapping a whip upon exiting the bar.

- Eisner, Fritz Lang, p. 161.

- Ibid.

- Elaine Frantz Parsons, “Race and Violence in Union County, South Carolina,” in Ku-Klux: The Birth of the Klan During Reconstruction, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2015, pp. 215-263. In her book, Parsons addresses the common event of imprisoned Blacks being yanked out of their jail cells and lynched at the hands of Ku-Klux Klan during the latter half of the nineteenth century.

- Eisner, Fritz Lang, p. 161.

- Robert A. Armour, Fritz Lang, Twayne Publishers, Boston, 1977, p. 106.

- Ibid.

- For more on the reading of this scene as a reflection on Lang’s Expressionistic style more commonly found in his German films, see Phillips, Exiles in Hollywood, pp. 38-39.

- Armour, Fritz Lang, p. 107.

- “H.R. 35: Emmett Till Antilynching Act – House Vote #71 – Feb 26, 2020,” GovTrack.Us, https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/116-2020/h71.

- “MonroeWorkToday.Org – the Rise of Lynching,” Monroe Work Today, http://www.monroeworktoday.org.

- Ibid.

- Robert W. Thurston, Lynching, Ashgate, Farnham and Surrey, 2011, p. 100.

- For more on Thurston’s three categories of lynching, see Ibid., pp. 92-101.

- Ibid., p. 97.

- “About the Equal Justice Initiative,” Equal Justice Initiative, https://www.eji.org/about-eji/.

- “Equal Justice Initiative’s Report,” Equal Justice Initiative’s report, https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/report/.

- Fritz Lang, Bartlett Cormak, Joseph H. Mankiewicz, Fury, DVD, directed by Fritz Lang, Warner Home Video, Inc., Burbank, CA, 2005.

- “Lynching,” Law Library – American Law and Legal Information, https://law.jrank.org/pages/8375/Lynching.html.

- For more on the history of lynching films, both pro- and anti-lynching narratives, and examples of how the theme of lynching has evolved in the 21st century cinema, see Robert Jackson, “A Southern Sublimation: Lynching Film and the Reconstruction of American Memory,” The Southern Literary Journal, vol. 40, no. 2, 2008, pp. 102-120.

- For more on the depictions of mob mentality in Metropolis and the role of vigilante justice in M, see Anton Kaes, “A Stranger in the House: Fritz Lang’s Fury and the Cinema of Exile,” New German Critique, vol. 8, 2003, pp. 47-48.

- D.W.C., “Fritz Lang Bows to Mammon,” New York Times, June 14, 1936. See also Armour, Fritz Lang, pp.106-107.

- “Equal Justice Initiative’s Report,” Equal Justice Initiative, https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/report/.

- Reynold Humphries, Fritz Lang: Genre and Representation in His American Films, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, 1989, p. 57.

- Ibid.

- Norman Rosenberg, “Hollywood on Trials: Courts and Films, 1930-1960,” Law and History Review vol. 12, no. 2, 1994, p. 355.

- Stella Bruzzi, “Imperfect Justice: Fritz Lang’s Fury (1936) and Cinema’s Use of the Trial Form,” Law and Humanities vol. 4, no. 1, 2010, pp. 15-16. Bruzzi does comment on how the district attorney identifies Ted Fitzgerald as the single cameraman who caught all of the footage which was used as evidence for this trial. Bruzzi states that she finds these shots to be “even more fantastical” than the vantage points offered to the spectator as the mob seizes control of the jail.

- Lang, Fury, 1936.

- Theodore F. Rippey, “By a Thread: Civilization in Fritz Lang’s Fury,” Journal of Film and Video vol. 60, nos. 3-4, 2008, p. 86.

- Rippey, “By a Thread,” p. 86.

- Kaes, “A Stranger in the House,” pp. 56-57.

- Tom Gunning, The Films of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity, The British Film Institute, London, 2000, p. 225.

- Thomas Elsaesser, Weimar Cinema and After: Germany’s Historical Imaginary, Routledge, London, 2001, p. 166.

- Bruzzi, “Imperfect Justice,” p. 1.

- Eisner, Fritz Lang, p. 173.

- Humphries, Fritz Lang, p. 55 (original italics).

- Ibid.

- Ibid., pp. 56-57.

- Ibid., p. 55.

- Ibid., p. 58 (original italics).

- Humphries, pp. 58-59. Humphries comments on the use of freeze-frames in Fury, writing, “[a] newsreel seeks to persuade spectators that what they are seeing is actually going on before their eyes, whereas the purpose of a photograph is to capture the past. Both past and present are now there before the stunned gaze of all those present, the moving images and the frozen frames thus overdetermining each other to present and even more ‘faithful’ image of reality.”

- Richard Pérez-Peña, “Woman Linked to 1955 Emmett Till Murder Tells Historian Her Claims Were False,” New York Times, 22 Dec. 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/27/us/emmett-till-lynching-carolyn-bryant-donham.html.

- DeNeen L. Brown, “‘It Was a Modern-Day Lynching’: Violent Deaths Reflect a Brutal American Legacy,” National Geographic, 8 Jun. 2020, https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/history-and-civilisation/2020/06/it-was-a-modern-day-lynching-violent-deaths-reflect-a-brutal; Eliott C. McLaughlin, “America’s Legacy of Lynching Isn’t All History. Many Say It’s Still Happening Today,” CNN, 3 Jun. 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/03/us/lynching-america-george-floyd-ahmaud-arbery-breonna-taylor/index.html.

- Tom Miles, “U.S. Police Killings Reminiscent of Lynching, U.N. Group Says,” Reuters, 24 Sep. 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-police-un-idUSKCN11T1OS.

- “About,” Black Lives Matter, https://www.blacklivesmatter.com/about/.

- Ibid.

- George Zimmerman, who was not a police officer but was patrolling as a neighborhood watchman when he shot and killed Trayvon Martin, is excluded from this qualifier.

- Paula Rogo, “Black Teen Assaulted by White Cop at Texas Pool Party Wins Settlement,” Essence, 20 Jun. 2018, https://www.essence.com/news/black-teen-white-cop-texas-pool-party-wins-settlement/.

- For more on recent developments and discussions around Sandra Bland’s case, see Dahleen Glanton, “Four Years after Her Death, Sandra Bland Gets to Tell Her Side of the Story,” Chicago Tribune, 10 May 2019, https://www.chicagotribune.com/columns/dahleen-glanton/ct-met-dahleen-glanton-sandra-bland-cellphone-video-20190510-story.html.

- A study that was conducted by the Nationscape Insights group showed that “96% of Americans acknowledged, to varying degrees, that black people face discrimination.” For more on this subject, see Rebecca Morin, “Percentage Grows among Americans Who Say Black People Experience a ‘great Deal’ of Discrimination, Survey Shows,” USA TODAY, 8 Jun. 2020, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2020/06/08/survey-higher-percentage-us-agree-black-people-face-discrimination/3143651001/.

- Katelyn Burns, “Why Police Often Single out Trans People for Violence,” Vox, 23 Jun. 2020, https://www.vox.com/identities/2020/6/23/21295432/police-black-trans-people-violence.

- This was despite having deeply-rooted societal reflections and believed to be strongly based on an event that took place in San Jose, California. Kaes’ article was published before McGilligan’s book Fritz Lang: Nature of the Beast, where he provides more detailed information on this connection, but Kaes comments that Krasna’s original storyline and Lang’s adaptation may have evolved out of an event that took place in 1933. Kaes states, “The screenwriter Norman Krasna and Lang may have taken their inspiration from a widely publicized kidnapping and murder incident in San Jose, California, in November 1933. When the body of the victim, the young heir of a department store, was found floating in the San Francisco Bay, a mob of 3,000 citizens stormed the county jail and seized the two men who had confessed the crime. Prison guards stood by as the mob pulled the men from their cells and hanged them on trees in an adjacent park.” See Kaes, “A Stranger in the House,” p. 50.

- Philip Rosen, Change Mummified: Cinema, Historicity, Theory, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2001, p. 234.

- Rosen, Change Mummified, p. 245-246.

- Ibid., p. 242.

- Ibid.

- Fury also includes examples of journalism through the medium of the newspaper, but the examples of print journalism fall outside of the scope of this article.

- Federal funding for the purchasing of body cameras across law enforcement agencies nationwide have greatly increased their adoption since 2015. See “Body Cameras May Not Be the Easy Answer Everyone Was Looking For,” PEW, 14 Jan. 2020, https://www.pew.org/36SQupF/.

- Shah writes on the ways in which wiretaps have been used to build cases against civilians despite wiretap laws being passed with the intention of protecting citizens from being recorded without written consent.

- Raoul Shah, “Cop-Watch: An Analysis of the Right to Record Police Activity and Its Limits,” Hamline Journal of Public Law & Policy vol. 37, iss. 1, 2017, p. 218. Shah also breaks down which court circuits have ruled that recording and photographing the police falls under the protection of the First Amendment.

- “The United States Bill of Rights: First 10 Amendments to the Constitution,” American Civil Liberties Union, https://www.aclu.org/united-states-bill-rights-first-10-amendments-constitution/.

- Shah, “Cop-Watch,” p. 219. For more on the ways that the First Amendment extends to video recording the police by way of making an implicit statement of observation/surveillance and as a form of art, see Laurent Sacharoff, “Cell Phone Buffer Zones,” University of St. Thomas Journal of Law and Public Policy (Minnesota) vol. 10, no. 2 (2016), pp. 94-113.

- Shah, “Cop-Watch,” p. 227. For more on this topic and on how video recording the police can pose a danger to both the police and the individual doing the recording, see Michael Potere, “Who Will Watch the Watchmen: Citizens Recording Police Conduct,” Northwestern University Law Review vol. 106, no. 1, 2012, p. 316.

- “The 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution,” National Constitution Center, https://www.constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/amendments/amendment-xiv/.

- “Circuit Court Law and Legal Definition,” USLegal, Inc., https://definitions.uslegal.com/c/circuit-court/. A circuit court is defined as “an intermediate appellate court of the United States federal court system.”

- Doxing is the practice of searching for and publishing private information that could assist in the identification of the targeted subject. See Dragana Kaurin, “The Price of Filming Police Violence,” VICE, 27 Apr. 2018, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/evqw9z/filming-police-brutality-retaliation.

- Kaurin, “The Price of Filming Police Violence.”

- Chloé Cooper Jones, “Fearing for His Life,” The Verge, 13 Mar. 2019, https://www.theverge.com/2019/3/13/18253848/eric-garner-footage-ramsey-orta-police-brutality-killing-safety.

- Ibid. Orta was arrested on a gun charge. In the article, he shares some of his fears and general experiences while being imprisoned, including harassment, attempted poisoning, and physical abuse.

- Ibid.

- “Whose Streets?,” directed by Sabaah Folayan, et al., Magnolia Pictures, 2017.

- “ACLU Apps to Record Police Conduct,” American Civil Liberties Union, https://www.aclu.org/issues/criminal-law-reform/reforming-police-practices/aclu-apps-record-police-conduct?redirect=feature/aclu-apps-record-police-conduct.

- “Human Rights Campaigns & Projects from WITNESS,” WITNESS, https://www.witness.org/our-work/.

- Jim Norman, “Confidence in Police Back at Historical Average,” Gallup, 10 Jul. 2017, https://news.gallup.com/poll/213869/confidence-police-back-historical-average.aspx.

- Doug Criss, “The One Thing That Determines How You Feel about the Police,” CNN, 14 Jul. 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/07/14/health/police-confidence-gallup-polls-trnd/index.html.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. Criss states that differences in life experiences and social media exposure to content pertaining to police shootings are the main reasons behind the dropping confidence in law enforcement among these demographics. For the Gallup surveys that report these findings, see Jim Norman, “Confidence in Police Back at Historical Average”; Jeffrey M. Jones, “In U.S., Confidence in Police Lowest in 22 Years,” Gallup, 19 Jun. 2015, https://news.gallup.com/poll/183704/confidence-police-lowest-years.aspx.

- Aisha Harris, “Fictional Police Brutality, Real Emotional Toll,” New York Times, 20 Jul. 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/20/movies/police-shootings-blindspotting-detroit.html. Writing on the way in which television has integrated the topic of police shootings into storylines, Aisha Harris of the New York Times placed television programs in conversation with one another to present how the topic of police brutality is presented on the small screen.

- German Lopez, “How Video Changed Americans’ Views toward the Police, from Rodney King to Alton Sterling,” Vox, 6 Jul. 2016, https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2015/12/10/9886504/police-shooting-video-confidence. Lopez’s article provides a breakdown of many of the high-profile shootings and altercations with the police that were captured on video in 2014 and 2015.

- Quoted in Anjuli Sastry and Karen Grigsby Bates, “When LA Erupted In Anger: A Look Back At The Rodney King Riots,” NPR, 26 Apr. 2017, https://www.npr.org/2017/04/26/524744989/when-la-erupted-in-anger-a-look-back-at-the-rodney-king-riots.

- Robert Evans and Jason Petty, “Behind the Police,” iHeart Radio, June-July 2020, https://www.iheart.com/podcast/1119-behind-the-police-63877803/. The podcast series “Behind the Police” focuses on the history of policing in America and its deeply racist roots. This podcast can be read as one of the programs that participated in shedding light on the ominous and deadly past and present of law enforcement agencies and how people of color have been targeted for generations.