But as each germ strives to develop, there necessarily arises a struggle for existence which manifests itself not merely as direct bodily combat or devouring, but also as a struggle for space and light, even in the case of plants.1

— Friedrich Engels

The term “squatting” refers to the actions taken to break into a vacant building and live there without the permission of the owner. Squatting is a political act that aims to affirm the right of use of an empty building against the principle of private property. It is by nature an anti-capitalist direct action that interferes with different forms of the accumulation of profit, such as rent extraction and real estate exploitation.2 In the twentieth-century Netherlands, one of the common characteristics of the squatters’ movement was its ability to promote its activities through the virtual space of media dissemination.3 This article investigates how the squatting movement in Rotterdam was able to adapt to a highly regulated urban environment via the production and distribution of documentary films that sympathetically portrayed their movement’s values and objectives.

The distinctive characteristic of these films is that the filmmakers involved were the squatters themselves. As a direct form of experiencing the everyday actions and lives of squatters, these filmic documents offer a way of exploring the complexity of a historical period that might otherwise pass unobserved or be forgotten and buried, especially since squatting was considered illegal, much as it is today. Loosely tolerated until the promulgation of the anti-squatting law in 2010, squatting in the Netherlands paradoxically continues to exist because it has been co-opted by capitalistic mechanisms seeking to enhance the economic value of properties in the city. Following a period of counterproductive and drastic urban renewal strategies in the late 1990s, local governments began to condone and support the occupation of buildings that offered small-scale cultural events and activities and fostered the socio-economic developments of their surrounding neighborhoods. Inadvertent promoters of the process of gentrification, many Dutch squats were converted into “providers of cultural rather than social services,” while the radical segments of the squatters’ movement, which criticized these urban transformations and struggled towards the objective of facilitating affordable housing, were gradually excluded from the city for their political convictions and activities.4

In 1983 the Spanish sociologist Manuel Castells stated that the squatting movement in the Netherlands “has become a major event in the field of urban struggles,” arguing that “as usually happens with any important movement, a myth and a controversy have developed about its meaning, content, goals, effectiveness and actual relevance.”5 Since then, a great deal of research has been carried out on the peculiarities of this important Dutch social movement, focusing primarily on the influential activities of the squatters’ movement in Amsterdam. Until now, the squatting movement in Rotterdam has played only a marginal role in the scholarship on this important social and political phenomenon. In filling this gap and analyzing the activities of Rotterdam’s squatters, I will explore a collection of their films as primary sources in order to reconstruct the history of the urban conflicts of the city. My aim is to analyze squatting in Rotterdam through its broad filmic activity and to describe the pivotal role of this forgotten chapter in the history of the Dutch squatters’ movement.

Completed between the 1980s and the 2010s, these films were somewhat amateur in their execution but were conceived, at the time, as a practical method for generating, preserving, and sharing knowledge on the squatting movement.6 Living in unoccupied buildings and with a predilection towards cinema, Rotterdam’s squatters began filming themselves in order to rapidly document events such as direct actions and evictions. During the early 2000s, Cineac TV/Pietje Bell Rotterdam, a now defunct local television station, played a crucial role in preserving and stimulating the work of these activist cinematographers by collecting and broadcasting their films (and in some cases even commissioning new films).7 Screened in the occupied buildings during public events and debates, broadcasted on Cineac TV, and, most recently, made freely available via a number of different web platforms, these self-organized cinematic compilations presented the squatters’ movement to a diverse audience and, equally as significant, facilitated the establishment of spaces of collective investigation. In 2016, the activist-research network SqEK (Squatting Everywhere Kollective) rediscovered these films and publicly screened them in Rotterdam during the Resistance to Gentrification event.

In Rotterdam, particularly during these counter-information screenings in the variously occupied social centers, the self-organized films sought to stimulate squatting and broader cooperation in the physical urban sphere. These activist cinematographers conceived of their films as sources of information that could improve the practice of squatting and open discussion regarding the outcomes of such action in the public sphere. In order to achieve these objectives, the films were developed by combining two different types of films: cinematographic reports that rapidly documented the developments of the groups’ squatting actions, and video tutorials that illustrated the various methods for breaking into buildings or dealing with the authorities. This self-organized cinema in Rotterdam can be considered a proper film genre based on four common aspects that are summarized as follows: 1. the setting of the film in a single occupied building or among a specific community of squatters; 2. the squatters as both protagonists of the films and their directors; 3. the use of the handheld camera with a first-person perspective as a method for offering the viewer the simulation of a real, or historically accurate, squatting experience; 4. the adoption of montage as a method for ensuring the longevity of the films’ contributions and impacts upon their viewers. Referring to these dimensions of self-organized cinema, this article focuses on what two specific films, Fietsenfabriek and Kraken in Rotterdam, reveal about the trajectory of the squatting movement in Rotterdam.8

Aims of the Discussion

A critical investigation of the squatters’ actions as portrayed through their self-produced films holds the potential of revealing hidden stories and new perspectives on urban conflict in the city. Squatting as an act leads to social scenarios and interactions that are as yet not very well explored or defined. Occupying a building and social center is far more than a practice of cultural innovation. Rather, it can directly transform the traditional methods of political action.9 In this process, the role of the films that arose from within the Dutch squatters’ movement was actually quite central to its self-representation and outward projection: these productions effectively enabled squatters to map problems inherent in urban development and design, to seek solutions by which to make occupied buildings a more permanent presence, and to empower people to come together in the form of social action.

The larger questions guiding this article revolve around the relationship between cinema, activism, and physical space. The purpose here is far greater than that of describing the most obvious and conspicuous aspects of capitalist exploitation in a city, such as speculation and gentrification. Rather, I aim to reread the city of Rotterdam with the concept of the “fabbrica sociale” (“social factory”) in mind. Coined by Italian thinker and leader of operaismo (“workerism”) Mario Tronti, this concept understands the city to be an organism that has the function of reproducing and organizing labor such that it will dominate all of society.10 The films examined here widely criticized this more subtle condition of urban development and depicted squatting as a means of sabotaging the “social factory.” In other words, squatting could interfere with urban productive capacity and, in this way, revolutionize society.

Squatting in the Netherlands

Since the mid-1960s, squatting in the Netherlands was self-organized and self-regulated according to specific protocols, strategies, and practices. The traditional steps followed included: making an inventory of all the vacant buildings in the city; organizing Kraakspreekuren (squatting information centers); and writing zines and squatters’ guidebooks to explain how to negotiate with the police, the owner of the building, or public authorities in the aftermath of an occupation, as well as the various legal implications of these activities.

At that time, squatting became a political activity on the urban scale. For example, in April 1966 the anarchist group Provo Movement released the “White House Plan” for the city of Amsterdam, which was essentially a list of vacant residential units. In order to make them visible and recognizable, the anarchists painted the entrance doors of the empty buildings in white.11 In May 1969 the Woningburo de Kraker (Squatters’ Housing Agency) also published the first “Handleiding voor krakers” (“Manual for Squatters”), with the motto “Do it yourself! Take the solution of the housing problem into your own hands.”12 Echoing the hammer and sickle, the communist symbol for international working class solidarity, the logo on the cover of this squatters’ manual depicted a hammer and crowbar. This symbol came to be adopted by the entire Dutch squatting movement. Over the years instruction books were published, and these inspired various groups to take action against building vacancy in the Netherlands. They were largely utilized as open-source tools to strategically organize the various phases of squatting, including: the mobilization of supporters; breaking into buildings and replacing the door locks; renovating the occupied buildings to make them habitable; communicating with the owner, police, and other involved authorities; and much more.

A curious satirical caricature drawn in 1981 for the self-published Rotterdam magazine Skwat Krakkrant depicts a young man as a linen sheet being twisted and dripping while a landlord squeezes the rent out of him. The liquid collecting bucket is labelled with the word “huur” (rent), symbolically representing the accumulation of rental profits.13 This caricature is suggestive of the shortage of affordable housing, which was the sole concern of the Dutch squatters’ movement until the early 1980s. During the subsequent decade, the movement expanded its focus. Rather than mobilizing for alternative housing strategies alone, it began organizing large-scale protests pushing for a much more widespread and radical transformation of society.14 Within this new framework of political action, occupied buildings began to provide free cultural and social services in the urban centers.

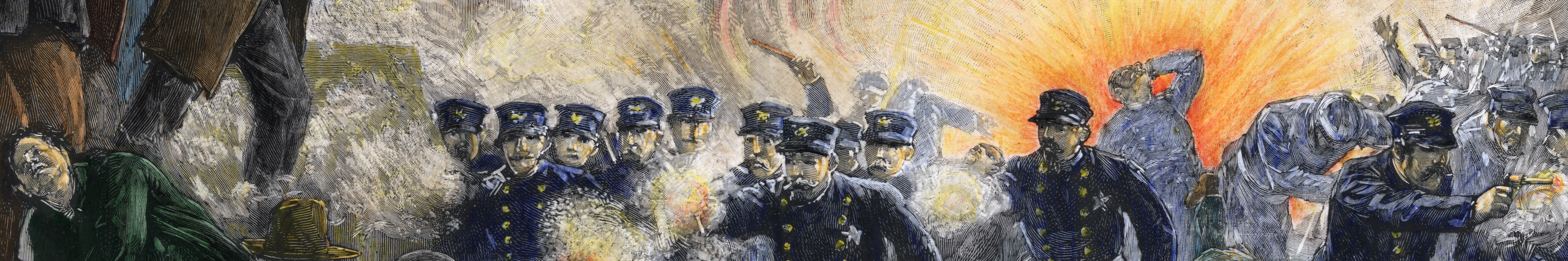

The movement also developed its own symbols of empowerment. On April 30, 1980, and following a series of violent evictions across Amsterdam, the movement proclaimed National Squatter Day. This was a symbolic move that took place on the same date as the investiture of Queen Beatrix. Under the slogan “Geen Wooning: Geen Kroning!!” (“No Homes: No Coronation!!”), the queen’s coronation was marked by the largest riot in the Netherlands since World War II, and it involved squatters from across the country, revealing the movement’s ability to mobilize all of its supporters in coordinated, collective actions.15 The coronation day riot in Amsterdam, therefore, can be considered the fundamental turning point of the squatting movement in the Netherlands.

Rotterdam: The Background

The squatters’ movement in Rotterdam was quite prolific. Although most of the squats were only residential, between the 1970s and early 2000s—the “Golden Age” of the squatting movement in the Netherlands—more than two hundred occupied buildings maintained a “public presence” through the events they organized, which were purposefully open to the public.16 Since the early 1980s, each neighborhood across Rotterdam hosted an occupied social center, all of which were self-managed and with strong anarchist affiliations.17

At that time there was an enormous number of vacant properties across Rotterdam. The complete relocation of harbor activities to the south side of the Meuse River and the shift towards more automatized logistical operations resulted in the abandonment of many industrial, commercial, and residential buildings. The city became a battleground between squatters and authorities, including both public authorities and the private entrepreneurs that wanted to generate revenue from the vacant properties.

Even if the squatters’ movement in Rotterdam did not specifically have a left-wing orientation and was not organized according to a central network like their counterparts in Amsterdam, it developed its own strategies, and these produced a number of significant results. By blocking neoliberal urban policies and resisting the commodification of buildings in the city, as well as their own lives, the squatters in Rotterdam constructed a dense political network that gave rise to a sort of autonomous city, an entity distinct from that of the productive city.

Because the groups organized a range of cultural activities, squatting can also be seen as the precursor of the creative industries that later contributed to the idea of the “productive city.” Since the late-twentieth century, the cultural and artistic innovation of squatters’ groups has been constantly re-evaluated and integrated “by governance as part of city cultural infrastructure.”18 In essence, the productive city is a model that promotes urban economic development policies by bringing together and supporting the necessary creative forces, including the social centers in which much of this activity took place, but also in convening artists and intellectuals that gave impetus to urban vitality and its social diffusion.19 In fact, the creativity typical of these squatters’ groups has drawn great attention and has proven an unlimited source of inspiration for a number of fields, including architecture, self-publishing, music, the visual arts, theater, cinema, and new media. Indeed, the squatting movement has more recently been re-read and re-evaluated as a complex urban and political phenomenon, with particular focus, for instance, on the “creativity” of self-made squatters’ architecture and the practice of screening experimental films within these informal spaces.20 However, the political actions of the Dutch squatters and the conflicts to which they contributed are hardly discussed in institutional and mainstream narrations, and discussions on productive cities in the Netherlands have given attention only to the creative value of squatting. In order to offer a more complete history of squatting in Rotterdam, the films examined in the following section are critical because they not only describe the cultural and political aims of the movement, but also show how those intentions manifested through forms of social and political agitation.

Self-Organized Films

Beginning in the 1980s a number of activist cinematographers in Rotterdam became interested in documenting the actions and protests of squatters in short films, such as Fietsenfabriek in het Oude Noorden (anonymous, 1984-1998, 30’), Untitled (STORT Collective, 1988, 8’), Kraken in Rotterdam (Melle van Rens, 2003, 29’), Waterloostraat (anonymous, 2003, 4’), The Factory Facts, De Fabriek (Jup De Heer, 2008, 16’), Cops & Squatters (anonymous, late 2000s), and Boerderij aan de Rotte (anonymous, 2012, 3’). These films aimed to translate tangible memories of the tactics and political disputes of the “wild” squatters’ movement into visual media, and to describe their visions of alternative ways of living, working, and making art and culture from within the struggle. The films described how a building was to be occupied from a number of cultural and political angles, such as instantaneous squatting actions in local neighborhoods and planned strategies to occupy and preserve various structures and buildings. This self-organized cinema was made with handheld cameras and sync sound recordings that provided a direct experience from within the occupied buildings and an inside view of the conflicts in which the squatters were invested. In this way they echoed documentary genres that sought to capture reality. They were also collective in nature and resulted from a continuous process of montage that allowed not only single filmmakers but also the entire community of squatters to revise the information and contribute their own perspectives.

Two of these films, Fietsenfabriek (Bicycle Factory) and Kraken in Rotterdam (Squatting in Rotterdam), are particularly revealing of the implications of squatters’ actions and their political efforts and effects. They allow us to peer into the squatting movement in Rotterdam during two different periods: when the movement was flourishing in the 1980s, and during its decline in the early 2000s.

The squatters’ movement in Rotterdam was characterized by the so-called “quiet riot,” or by constant, daily acts of occupying empty buildings, acts that occasionally involved public disruption and street fights.21 One of these significant moments is narrated in the film Fietsenfabriek, which documents a violent conflict that erupted for one day in 1984 as squatters defended their occupation of a vacant historical building that they had transformed into a public venue. The “quiet” squatters are also the protagonists of Kraken in Rotterdam. Filmed in 2003, during one of the most critical periods for the Dutch movement, it shows the squatters’ attempts to politically justify their position and clarify their strategies, which can be read in opposition to the negative reports issued by the politicians and the mainstream media, and against the co-optation of the movement by local authorities.

While Kraken in Rotterdam is a notable example of handheld camera work, Fietsenfabriek is peculiar because of the continuous process of montage that relied on ongoing revisions and transformations of the film over a number of months and even years. The freedom of movement the handheld camera allowed became a unique element of these films, and through this medium Kraken in Rotterdam in particular emphasized the tensions within the squatters’ social world and facilitated the interaction with the viewer. The result of this cinematic technique was a shaky image that resulted from what appeared to be a spontaneous filming of reality. Rather than a mere recording tool, the handheld camera transferred and intensified how the squatter perceived his or her surroundings and projected their political views onto them. Simulating a bodily experience, the shaky and mobile gaze of the squatter filmmaker allowed them to communicate empathy and embed the viewer in the space of conflict.

Of the films produced by the squatting movement in Rotterdam, Fietsenfabriek is the most emblematic case of montage as a continuous and spontaneous process of filming and revision that updated the plot and depictions of events with new information. As an example of ante litteram crowdsourcing, such self-organized films were tacitly intended as open-structure works that the squatters’ community could transform and revise by montage at a later time.

The squatters’ open-structure films seemed to refer to Dziga Vertov’s “kino-object,” in other words, a film that can be continuously modified by the author but also concretely “manipulated” by others, those who were “competent spectators.”22 By editing the first version of the film later, sometimes over many years and in a relatively unplanned process, the squatters aimed to collect additional and more recent information that had not been included in the previous version. The films could be modified or reconstructed with extra handheld shots, footage found later, interviews, recorded audio, voice-overs, or complemented by satirical subtitles.

Cinema and Activism

These selected films can intrinsically be considered film essays. In his book Theory of Film Practice, American film theorist and filmmaker Noël Burch stresses the differences between the typical documentary and the film essay. While the former represents “an objective rendering of the world,” a “sort of reproduction of reality” characterized by a temporal and spatial “flat continuity” of the montage, the latter is “discontinuous” and “ambiguous”; it expresses an “active” interpretation of the theme analyzed and can also include “pre-existing filmic materials.”23 The film-essay genre clearly defines an idea and takes a strong argumentative position; as such, it does not represent any objective or neutral point of view. Thus, through the direct knowledge of their tactics and the purposes driving their media expression, the squatters did not just document their activity but critically explored and interpreted the consequences of their actions during the occupations.

In his 1968 “Cinema e politica” (“Cinema and Politics”), published in the first issue of Contropiano, an Italian journal dedicated to themes of capitalism and class struggle, Alberto Abruzzese explored the incoherence of certain films that contained political elements of protest yet sought to analyze them in an “objective” way.24 In fact, in Abruzzese’s view, artistic productions that assumed a revolutionary ideology as their main purpose but positioned themselves outside of “completely lived experiences” revealed an “ironic” character.25 As we have seen, however, the filmic expressions of the squatters’ activity did not fall into this contradictory position, as they were able to link the two different objectives. One concerned their anti-capitalist strategies, especially in the realm of property rights, and the other was the human experience of the squatters’ daily lives within the struggle. By documenting and showing the desperate and organized forms of resistance during an eviction (Fietsenfabriek) and the legal issues related with the occupation of a building (Kraken in Rotterdam), these films represented different political struggles that all led to the squatters’ defeat, the failures of their tactics, and their subsequent evictions from the occupied buildings.

Beyond their defeats in the urban context of Rotterdam, however, these films offer unexpected insight and meanings based on the relationship between cinema and activism. The squatter filmmakers, who were both familiar with the lived space of occupied buildings and involved in the dual role of production as filmmakers and film protagonists, can be said to have had a phenomenological role through their function of rereading and projecting real, affective experiences with new meaning for the public. In Kraken in Rotterdam, the squatter filmmaker Melle van Rens revealed a notable case of the bodily adaptation to cinematographic technologies. Melle was naturally capable of moving easily through the spaces of the occupied buildings and transferring his perceptions to the viewer. With the goal of bringing the viewer into the battlefield, on the other hand, Fietsenfabriek entailed a complex reconstruction of an eviction which included various film and audio sources. The cinematic gaze of these two selected films mainly emphasizes the contradictions of aggressive urban policies, aiming to show alternative possibilities for the public use and transformations of buildings to integrate them into the urban fabric in a new way.

Squatting as an Alternative Urban Planning Practice: Fietsenfabriek

In 1981, one year after the massive riot in Amsterdam, the Dutch parliament approved the “Vacant Property Act,” stating that there is no criminal offense when an empty building is occupied after six months of vacancy. This law can be read as an institutional statement towards the pacification of the Dutch squatters’ movement following the violent conflicts of the previous year.26 Even though squatting was tolerated until 2010, the threat of evictions was never completely absent. Within this transformed political context, and following years of vacancy, in November 1983 a former fietsenfabriek (bicycle factory) was occupied in the neighborhood of Oude Noorden (Old North) in Rotterdam. The following April the building was evicted of its squatter inhabitants. The film Fietsenfabriek illustrated the squatters’ attempt to resist the eviction and demolition that did, however, subsequently take place. The film emphasizes three aspects in particular: the enormous potential of the occupied building as an alternative way to live; the self-coordination of squatters’ networks in cases of emergency; and the dramatic events on the day of the eviction.

Originally built in 1892, the building was entirely renovated by the squatters that planned and integrated living spaces with flexible arenas for public activities. They created spaces for a restaurant, ateliers, workshops, and a multifunctional room for exhibitions, screenings, and theater productions. The bicycle factory became the main reference point for the entire neighborhood, where four hundred residential units had already been occupied, as the film reported. At that time the municipal council was drawing an urban plan for Oude Noorden that would transform the neighborhood. This was already being implemented through the demolition of empty historical buildings.27

Through the narration, the film criticizes the cheap and unexceptional housing projects that were being realized in the city at that time.28 For instance, as one squatter declared in the film, the squatters occupied the bicycle factory in a statement of opposition to its “useless demolition” and with the aim of preventing the replacement of the integrated and public-use historical structure they had created with a “dull” residential building with no social or public functions. In relation to that specific urban plan, the spontaneous squatting actions in the neighborhood of Oude Noorden can be considered an alternative approach to preserving historical buildings from speculative real estate initiatives.29

The film Fietsenfabriek can be considered a sort of kino-object. It has been transformed and updated several times by different squatters to continuously adapt the storytelling to new sources and findings. It was periodically edited over fifteen years and disseminated in at least two versions, one is a thirty-minute film and the other in a shorter eleven-minute cut. The first version includes different kinds of materials, such as the original footage of the eviction as it was filmed by the squatters, along with the footage from television journalists, interviews at the city archives with protagonists and experts on the question of urban design, newspaper clippings, and recorded audio clips of the squatters’ efforts at resisting the police. The second version is a shorter edited version without many of the interviews, but it does include English subtitles.

The film begins by showing the evening edition of NOS Journaal, the television news report of the Dutch public broadcaster. On April 4, 1984, the show’s announcer concisely introduced the following one-minute report stating that local “police evict[ed] an occupied factory in Rotterdam.” As is usual for the mainstream media, the report was recited with a detached neutrality. The commentator’s voice seemed to echo a telegraphed message:

This morning at 10 o’clock the bailiff came with the eviction order. The thirty squatters have to leave the former bicycle factory to make way for apartments. But in response the bailiff was squirted through the door with ammoniac. A police officer got it in his eye and had to go to the hospital […] Further up the street, the squatters tried to occupy the institutional neighborhood center. In the scuffle, two cornered cops fired warning shots. There is word that people were wounded. At 16 o’clock the door of the squat was forced open with a truck, and the twelve squatters still inside were taken away by the officers.

By focusing on detailed descriptions of the incidents during the evictions and minimizing the significance of the gunshots the police issued as “warning shots,” the television report was typical of mainstream media coverage that, since the 1980s, has always depicted the squatters as “folk devils.”30 In the following scene, the critical reconstruction of the events surrounding the eviction shows a clip from an exhibition about the occupation of the bicycle factory. The interview with the curator, probably one of the squatters involved, is suddenly interrupted by the loud sound of the original audio of the eviction recorded by the squatters of Krakend Oude Noorden pirate radio. The clear sound of two gunshots, the screams of a wounded squatter, and the shocked reactions of other activists around him bring the viewer directly into the battlefield of the protest that is widely shown in the film. In this way they draw an important contrast against the dry and detached delivery of the NOS Journaal news report.

The epicenter of the riot took place at an abandoned construction site, left empty by the demolished buildings and its contours defined by the remaining mounds of sands, debris, bricks, and pipes. Accentuated by this natural scenography, which completely changed the appearance of the neighborhood, the battlefield was extremely different from that implied by the mainstream representation, and it included considerable participation by the squatters’ community of Rotterdam. Squeezed into this disrupted landscape, the protagonists—thirty squatters at the bicycle factory and many activists from other neighborhoods—resisted the policemen who were attacking on foot, on horseback, and with armored vehicles. Two panoramic shots showed that squatters also positioned themselves on the roofs of the occupied buildings in the neighborhood. Under a shiny purple sky, a bizarre color that probably results from the film’s physical degradation, a squatter climbs the chimney of the factory that has been symbolically reconquered. In this emblematic scene, they raise a pirate flag on top.

The film Fietsenfabriek leads the viewer to reflect critically on the outcomes of the irrational urban design of the neighborhood and the counter-productive efforts to commercialize the city. “The city is more than just a dormitory. Was it not precisely that mixture of functions that made the city so attractive as a residential area? Was it not precisely that ‘breeding place function’ of the old neighborhoods that was so important for the development of the economy?,” the squatters stated in the film and on one of their flyers. In their view, the bicycle factory was squatted for the purposes of “living, working, art, culture, and so on.”31 Rather than solely referring to an assemblage of single functions in a building, this motto implicitly described the aim of eluding those rules of the productive city that were perceived as unbearably restrictive and to design, instead, an alternative spatial diagram that could be freely occupied. “Living” is for free, with no rent and no mortgage; “working” means to produce objects that are needed for daily life; “art and culture” are free and open to anyone. The intention was to stimulate the inhabitants towards the liberation of their city from urban changes that were based exclusively on the exchange value of properties and commodities.

The film’s final scenes show the demolition of the factory. The camera lingers particularly on the destruction of the tall chimney, an urban point of reference on the horizon of Rotterdam, which was symbolically climbed during the eviction. The film then ends with a panoramic view of the empty battlefield, while in a voice-over the narrator says “now, fifteen years later the dust has settled and almost everyone gets along.”

Squatting as an Everyday Action in the Urban Landscape: Kraken in Rotterdam

According to Saskia Sassen, an urban renewal process seeks to concentrate new economic activities, services, and capital in the city and to generate the conditions for new populations to move in.32 In the early 2000s, Rotterdam was rapidly transformed through an urban regeneration process that consisted of a substantial replacement of its inhabitants.

Since the 1990s an anti-squatting sector had emerged in the Netherlands that aimed to prevent the occupation of buildings, to protect private property, and to provide profit to their clients, the building owners. Through the competitive renting of vacant buildings like houses, office blocks, schools, and farms, which were offered to temporary residents, real estate agencies “capitalized on the shortage of affordable housing.” Subjected to restricted conditions, such as the short notice to leave, anti-squatters could be considered “live-in guardians” that gradually replaced squatters in the Dutch cities.33

In a well-known official document in 2006, the municipality of Rotterdam openly stated that it aimed to regenerate “problem areas” by moving in more “desired households.”34 Echoing the productive nature of the city, the municipal government intended to attract creative and hardworking people in order to collect a larger tax revenue for the municipal treasury. Therefore, because of their reluctant attitude towards the profit-making exploitation of labor and resistance to these practices, radical squatters were considered “undesirable” subjects. In this period during the early 2000s the eviction-related incidents actually contributed to the campaign against squatting and provided a major source of propaganda. They depicted the squatters as groups that threatened social order, and the discussion around their actions gradually culminated in 2010 with the ban on squatting for the pronounced aim of defending inviolable private property.35

Filmed in 2003 within these local and national contexts, Kraken in Rotterdam can be understood as a counter-information report. Illustrated as a contemporary manual on squatting, this film aimed to offer practical actions for how to occupy a building for housing needs or public purposes and what typical living conditions characterized a squat.

Melle, a nineteen-year-old squatter, was the director and the chief protagonist of the film. Through the sync sound of his voice and the handheld camera that worked as an extension of his body and perfectly followed his movements, he is simultaneously the film narrator and camera operator.

According to Melle, at that time “Rotterdam was still considered a squatting paradise because it offered plenty of vacant buildings to satisfy needs of all kinds.”36 Seeking to clarify his position to the viewer and stimulate action, in the opening scene Melle briefly described his own squatted residence, which combined living spaces with others that had a public function. Through a panning shot, the frame moves from the window to the interior showing an exhibition room for artists, which is curiously clad with orange juice cartons. His house was typical of the self-made architecture of squatters that, regardless of the scale of the occupation, usually combined two purposes: the urgent need for a residential space, and the desire for a collective space for sharing with the public.

Structured as a filmic tour of various occupied buildings, the film is based on a series of twelve interviews with squatters that guide the viewer through their own dwellings and collective spaces. Melle moves with his handheld camera beside the characters or stays behind a fixed position of the camera. The interviews revolved around three main topics, including: squatting a single apartment; living in an anti-squat; and squatting as a method for establishing a social center with a larger public and urban outreach purpose.

The narration of Kraken in Rotterdam is often rather paradoxical. For instance, in order to emphasize the many options for individuals to squat in Rotterdam, shots from the outside show the boarded-up windows of many vacant residential buildings, while later on the film shows squatting to be a difficult and repressed action that requires a structured organization with specific methods and knowledge. “I really like to live like this, but it’s not an easy option,” one squatter says in an interview. Another paradoxical situation is revealed throughout the narration. There are two cases of contradictory anti-squats included in the film. While the first seemingly illustrates the benefits of an anti-squat, the second comically shows its illogical limitations. In order to depict the restrictive conditions that regulate the space of an anti-squat, the camera follows an anti-squatter through a long take that allows him to move across the labyrinthine building without forcing a cut in the film sequence. During this interview the inhabitant moves in a long corridor from the living room to the kitchen through a series of outdated fire doors that are alternatively opened and closed. At the fifth door, Melle spontaneously starts laughing while the anti-squatter says, “Yeah, weird huh?” Since restructuring the interior is contractually not permitted, the “live-in guardian” absurdly lives within the former functions of the building.

Largely shot in the interiors of these occupied spaces, Kraken in Rotterdam illustrates a mixture of different spaces that can still, however, be viewed as a single entity created by editing the scenes shot in several squatted buildings. These include ten residential squats, including the squat café De Paardeval, the TDK squat which hosted techno music festivals, and the Schieblok, a former office building in the city center. The continuous film sequences of their interiors can be considered a re-composition of various spatial fragments that generate an imaginary urban block, an autonomous body that aims to find an alternative approach of living in capitalist society.

Mugel, one of the squatters interviewed, can be considered the co-protagonist. He appears in three crucial moments: during the interview at his place, which describes what squatting is and how society perceives it; during a nocturnal move to occupy a vacant apartment; and, finally, for the legal issue of the Schieblok that had just been occupied.

Mugel’s interview takes place in a psychedelic room decorated with his pasted-paper artwork, such as a fluorescent green head of a dragon and a crowd swallowed by a striated tunnel. In his view, an empty private property is a shame “because so many people are waiting for a house.” For the Dutch, Mugel lamented, “squatting sits in the taboo sphere,” because even if squatting is legal, many people actually consider it illegal. Although “the act of breaking a door is illegal,” he mentions that according to law an occupation is considered “legal” whenever the squatter provides “a bed, a chair, and a table, and also a new lock for the door” to legitimize his or her right to decent and affordable housing.37

Concerned about the misinformation that so often shapes public opinion, Kraken in Rotterdam particularly focuses on the fundamental rules and protocols of squatting. In one of the interviews, a squatter described all of the tools that were needed in order to quickly break into, and obtain control over, a vacant building. During this part, the film turns to a more practical point of view and accurately documents a nocturnal squatting activity beginning with first phases, which include people gathering and loading a cargo bike with a bed, chair, and table. While a squatter is trying to break the lock of a front door, the suspense is suddenly interrupted by Melle as he asks “what are we doing here?”

The legal issue of the occupied Schieblok is the turning point of the film. This scene begins with the shot of a ready-made object, the billboard on a facade that advertises a real estate project with an ambiguous slogan: “behind the facades lies a new future.”38 Rather than waiting for the “new future” of a speculative project, Mugel guides Melle into the Schieblok to describe how the group of squatters plans to develop a social center. He also describes the possibility of an eviction even before the court reaches its decision.

The film then reports the meticulous work that the Schieblok squatters carry out in order to prepare for their trial. Finally, Mugel expresses his disappointment over the verdict in favor of the real estate company and a comical frustration over the intrusive presence of the interlocutor and his camera. “Now get out, I’ve had enough of you!” The last scene symbolically summarizes the essential characteristic of the movement in Rotterdam, the everyday squatting actions. Standing at the front door and with his fist up, Mugel exclaims “tot ziens!” (“Goodbye!”) to implicitly refer to the next action.

Epilogue

In October 2010, only one month after the ban of squatting in the Netherlands, the inhabitants of Poortgebouw, a gated building located in the historically industrial area of the port of Rotterdam along the Meuse River, decided to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of its squatting community with an exemplary and fully illustrated poster. The collage includes a picture of the exterior of the building that is overlapped by an exotic background with palm trees, a sandy beach, and a calm sea. Through this poster, the past and present of the squatting movement in Rotterdam is simultaneously visualized. With the representation of their isolation, the “island dwellers” seem to allude to their role within the two historically opposed periods of squatting in the city. One is the period in which the movement flourished, when Poortgebouw was part of a big archipelago of occupations capable of resisting the financial exploitations of properties, while the other is the period of decline, when Poortgebouw became the last prominent squat in Rotterdam.

Over the last twenty years, radical and political squats have slowly been replaced with profit-making businesses or creative activities. For instance, the Fietsenfabriek social center has been replaced with a housing building and the Schieblok has become the location for a number of design firms. The ambivalence of squatting is characterized by the opposite reception of its creative functions and political actions. The relevance of squatting not only lies in the aesthetic qualities of the artistic forms created therein from time to time, but in the total and unquestionable freedom of choice through which these filmic works, for instance, were conceived and made available from within the conflicts and occupied buildings.

In Rotterdam the ambivalent function of squatting was resolved with drastic operations, such as the destruction of occupied buildings. In this way, a damnatio memoriae was levied against oppositional entities that generated conflicts in the urban sphere. The municipal authorities managed to completely eliminate the presence of a squatting network in the city. In light of these circumstances, the films Fietsenfabriek and Kraken in Rotterdam have become a visual and historical record of the squatters’ movement, which described the mechanisms by which followers can, and should, elude the rules of the property market, to counter the interests of those seeking to speculate on the properties, and to establish autonomous entities that function beyond the objectives of urban productivity.

Today, a screening of these films can be seen as a return of the repressed, something hidden and buried that can re-emerge and perhaps be seen as an irreducible dimension of Rotterdam’s character. Squatting can simultaneously appear to the viewer as uncanny and familiar, yet understanding its political meaning can lead us to resort to the practice once more as a “struggle for space and light”39 within the contemporary urban context.

Notes

- Friedrich Engels, Anti-Dühring. Herr Eugen Dühring’s Revolution in Science, Progress Publishers, [s.l.] 1947, available at the link: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/anti_duhring.pdf [retrieved on 10/27/2020]. This book was originally published in German in 1878.

- Miguel A. Martínez, Claudio Cattaneo, “Squatting as an Alternative to Capitalism: An Introduction,” in: The Squatters’ Movement in Europe: Commons and Autonomy as Alternatives to Capitalism, Pluto Press, London 2014, pp. 1-25.

- Alan Smart, “Squatting and Media: An interview with Geert Lovink,” in: Making Room: Cultural Production in Occupied Spaces, co-published by the Journal of Aesthetics & Protest and Other Forms, [s.l.] 2015, pp. 58-70.

- Justus Uitermark, “The Co-optation of Squatters in Amsterdam and the Emergence of a Movement Meritocracy: A Critical Reply to Pruijt,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 28, no. 3 (2004), pp. 687-698.

- Manuel Castells, “Squatters in the Netherlands: Elements for a Debate,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 7, no. 3 (1983), p. 405.

- The media production of the squatters’ movement was enormous, but in Rotterdam all of these archival materials are mostly fragmented and have not yet been organized. In 2017, Het Nieuwe Instituut, which hosts the Dutch archive of architecture, promoted an exhibition and two publications on squatting and acquired the archive of Poortgebouw, a legalized squat in Rotterdam. I also consulted the documents collected by Professor Hans Pruijt from the Department of Sociology at Erasmus University. When not available as open-source materials, I obtained these films by contacting people that were directly or indirectly involved in the mentioned squats.

- Interview with Melle van Rens, the author of the film Kraken in Rotterdam, held on 10/26/2020.

- These films are published on the website squat.net. The eleven-minute version of the film Fietsenfabriek is available at https://videos.squat.net/nlen-subs-eviction-of-bicycle-factory-rotterdam and Kraken in Rotterdam is at https://videos.squat.net/videos/watch/d5ea0ed3-2b7b-41f0-817e-a56372231af9 [retrieved on 10/27/2020].

- Primo Moroni, Daniele Farina, Pino Tripodi, Centri sociali: che impresa!, Castelvecchi, Rome 1995, pp. 5-15.

- For the meaning of “fabbrica sociale,” see Mario Tronti, “La fabbrica e la società,” in Operai e Capitale, DeriveApprodi, Rome 2006, pp. 35-56. This book was originally published in 1966. An English translation of the book chapter in question is available at: http://www.libcom.org/library/factory-society/ [retrieved on 10/26/2020].

- Eric Duivenvoorden, Een voet tussen de deur: Geschiedenis van de kraakbeweging 1964-1999 (A Foot in the Door: History of the Squatters’ Movement 1964-1999), Uitgeverij De Arbeiderspers, Amsterdam and Antwerp 2000, pp. 19-21. Kraken, meaning “to crack,” is the Dutch verb that defines a squatting action.

- Ibid., pp. 31-32.

- Anonymous, “Woonlasten, geen woonlusten” (“Living Charges, No Living”), Skwat Kraakkrant, no. 3 (1981), p. 9. The above-mentioned caricature was sketched for this article. The PDF file of the zine is available at: https://www.archive.org/details/Skwat3 [retrieved on 10/26/2020].

- Pruijt, “The Logic of Urban Squatting,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 37, no. 1 (2013), pp. 19-45.

- Duivenvoorden, Een voet tussen de deur, pp. 166-177.

- The activist researchers of SqEK (Squatting Everywhere Kollective) made a digital and interactive map that illustrates the data on occupied buildings, including those that experienced evictions, across eighteen European cities. The map that shows 228 squats in Rotterdam is available: https://maps.squat.net/en/cities/rotterdam/squats# [retrieved on 10/26/2020].

- E.T.C. Dee, “The Political Squatters’ Movement and Its Social Centres in the Gentrifying City of Rotterdam,” in: The Urban Politics of Squatters’ Movements, Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2018, pp. 187-208.

- Alan W. Moore, “Whether You Like It or Not,” in: Making Room, pp. 12-19.

- For an overview about the creative city, see Jamie Peck, “Struggling with the Creative Class,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 29, no. 4 (2005), pp. 740-770.

- René Boer, Marina Otero Verzier, Katía Truijen, The Architecture of Appropriation: On Squatting as Spatial Practice, Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam 2019, p. 22.

- Dee, Squatting the Grey City, Cobble Books, Rotterdam 2018, p. 10.

- Dziga Vertov, L’occhio della rivoluzione. Scritti dal 1922 al 1942, edited by Pietro Montani. Mimesis Edizioni, Milan-Udine 2011, pp. 14-16.

- Noël Burch, Theory of Film Practice, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 1981, pp. 59; 158-161. See also the first chapter “Spatial and Temporal Articulations,” pp. 3-16. This book was originally published in French as Praxis du cinema in 1969.

- Alberto Abruzzese, “Cinema e politica”, Contropiano: materiali marxisti, La nuova Italia, Florence, no. 1 (1968), pp. 171-179. This journal was published from 1968 to 1971 and was edited by Alberto Asor Rosa, Massimo Cacciari, and Antonio Negri. One of the journal’s fields of study was focused on the critique of ideology and culture.

- Ibid., p. 173. [The author translated the quoted parts from the original article.]

- Hugo Priemus, “Squatters in the City: New Occupation of Vacant Offices,” International Journal of Housing Policy, vol. 15, no. 1 (2015), pp. 84-92.

- Among the documents provided by the former squatters of Fietsenfabriek and archived at the Erasmus University, we can find clippings of the June 14, 1984 edition of the Dutch newspaper De Noordergids. The full-page article titled “Sloper verandert stadsbeeld van Het Oude Noorden” (“Demolisher Changes the Cityscape of the Old North”) illustrates the urban renewal project of the municipality. The article includes three significant images: 1. the picture of demolished buildings and debris; 2. the master plan that, based on large-scale demolition plans, aimed to reduce urban density and generate more green areas in the neighborhood; 3. the advertisement of a new shopping mall in the city, where the demolished retail stores were paradoxically located outside of the neighborhood.

- For a complete history of the common and irrational building demolition strategies in the city of Rotterdam, see also the film Rotterdam 2040 (Gyz La Rivièr, 2013, 95’).

- For an overview of the squatters’ tactics for the preservation of urban landscapes against the efficiency-driven planned transformations, see the section on “Conservational Squatting” in Pruijt, “The Logic of Urban Squatting,” pp. 19-45.

- Dee, “The Production of Squatters as Folk Devils: Analysis of a Moral Panic that Facilitated the Criminalization of Squatting in the Netherlands,” Deviant Behavior, no. 37 (2016), pp. 784-794.

- The original motto in Dutch is “wonen, werken, kunst, kultuur, enz.” See the flyer in Dee, Squatting the Grey City, Cobble Books, Rotterdam 2018, p. 109.

- Saskia Sassen, The Global City: New York, London and Tokyo, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1991.

- Tino Buchholtz, “Creativity and the Capitalist City,” in: Making Room, pp. 42-51.

- Gemeente Rotterdam (City of Rotterdam), Bouwen aan balans, actieprogramma Rotterdam zet door. Evaluatie en aanbevelingen (Building in Balance, Action Programme Rotterdam Perseveres. Evaluation and Recommendations), 2006, p. 15. The document is available at the city archive at: https://collecties.stadsarchief.rotterdam.nl/detail.php?id=1591304.

- Pruijt, “Culture Wars, Revanchism, Moral Panics and the Creative City. A Reconstruction of a Decline of Tolerant Public Policy: The Case of Dutch Anti-squatting Legislation,” Urban Studies, vol. 50, no. 6 (2013), pp. 1114-1129.

- Interview with Melle, 10/26/2020.

- In 1914 the Dutch Supreme Court declared that “a bed, a chair, and a table” are the conditio sine qua non to establish a residency in a former vacant building. See Duivenvoorden, Een voet tussen de deur, p. 14.

- The original slogan in Dutch is “achter de gevels schuilt een nieuwe toekomst.”

- Engels, Anti-Dühring.