Introduction: Remembering the Masacre de las Bananeras

2018 marks the 90th anniversary of what has become known as the masacre de las bananeras in Colombia. On December 5, 1928, banana plantation workers who were on strike against the transnational corporation the United Fruit Company (UFC, known today as Chiquita Brands International, Inc.) gathered to protest unfair labor practices. In the main plaza of Ciénaga—the geographical hub of the banana-producing zone located in the department of Magdalena on Colombia’s Caribbean coast—these workers hoped to negotiate their petitions with the UFC’s managers. Shortly after midnight, General Carlos Cortés of the Colombian army dispatched his troops to the plaza and opened fire on the crowd killing what remains an unknown number of people, either in the hundreds or thousands. The Banana Massacre, or masacre de las bananeras, has since fallen into history as folklore and myth, eulogized by literary giants and represented symbolically by visual artists. In the nine decades since the tragedy, the events of that night and the actual number of victims remain officially suppressed by governing forces in Colombia. The involvement of the United States (US)—in both the events that led up to the masacre and in the exploitation of Colombia’s banana industry which continued during subsequent decades—has never been openly reconciled.

This essay considers the Banana Massacre on the tragedy’s ninetieth anniversary, and how Colombian authors and contemporary visual artists engage with the legacy of the masacre, intertwining a history of violence, erasure, racial politics, and class struggles of plantation workers throughout the Caribbean. In this study, we move beyond the economic and political relationships of empire by adopting a materialist approach that focuses on the banana as object. In this fashion, the banana becomes a political actor in the drama of food and rememory as a form of resistance. Colombia’s artistic community has kept the tragedy unforgotten, maintaining an oral history which remains alive in their works. In this survey on the impact of the Banana Massacre, we examine Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967) and Carlos Arturo Truque’s short story “El encuentro” (1973) as representative of the literary tradition in which reality, fiction, imagination and interpretation are intimately intertwined. García Márquez’s masterpiece is the most globally recognized work that called attention to the massacre forty years after it took place. His use of so-called “magical realism”—the popular and marketed name given to a literary recording of oral story telling traditions common in the Caribbean—brought the tragedy to light, while also turning the event into folklore. Truque’s work, much less known than García Márquez’s, references the massacre to explore a point of view that had not been examined previously: the Afro-Colombian narrative on violence tied to banana cultivation and transnational exploitation in the Caribbean.

Also shedding light on these elements within labor relations are contemporary Colombian artists Liliana Angulo Cortés and Gonzalo Fuenmayor. Both artists take up the banana as an Afro-Colombian signifier by exploring the performative aspects of the fruit within popular culture. Angulo Cortés’s banana performances focus on the relationships between the banana, the black body, consumption, and agro-industrialization. Fuenmayor’s banana performances and works on paper both address the history and rememory of banana labor politics, violence, and the vulnerability of edible masculinities, embodied by the trope of the hypersexualized “Latin lover” as a consumable entity. In this essay, we explore how the disappearance of the consumable (banana) body and the erasure of the collective memory of the massacre become a singular disappeared entity embodied by gendered and racialized subjects in communities in Colombia’s Caribbean territories, and how their historical representation in literature and visual arts serves as an example on the role food has historically played in the construction of imperial systems and the emergence of global power dynamics. Our goal is to offer a perspective on food and resistance, identity, and community that invites dialogue and promotes an equitable cultivation and marketing of the banana, while keeping at the forefront the socio-historical importance that the ninetieth anniversary of the tragedy of the Banana Massacre represents.

Although rememory is a term traditionally assigned to literary analysis, it can be applied across disciplines. Rememory, as we use this term within this study, refers to the struggle of reconciliation and remembering of traumatic experiences that are often tethered to a landscape, a place, or collective testimonial. Rememory is quite often associated with the work of author Toni Morrison and Caribbean intellectual Édouard Glissant. Morrison’s novel Beloved (1987) is a “rememory” of the story of Margaret Garner and the haunting of her deceased child. Garner was a runaway enslaved woman in the US who was eventually caught. In order to avoid the re-enslavement of her family and further punishment, she murdered her youngest child who is believed to return in the narrative as an angry apparition. Rememory is thus also connected to the larger cultural ethos of the Black Atlantic and histories of enslavement. Glissant, one of the foremost Caribbean intellectuals of the twentieth and early twenty first century, could well have been referring to the work of García Márquez and Truque when he wrote in Poetics of Relation (1997): “Memory. After the System collapsed the literatures that had asserted itself within its space developed, for the most part, from the general traits so sketchily here” (70-71). Because the memories of the Banana Massacre have been largely erased, rememory acts as a recovery method to sketch out the general traits, details, and contingencies of the tragedy. Referring to cultural traditions of marronage (settlements of runaway enslaved persons), Glissant goes on to say, “But the truth is that their [maroons’] concern, its driving force and hidden design, is the derangement of the memory, which determines, along with imagination, our only way to tame time.” (71). Rememory is what connects the work of these authors and artists, and functions as a way to collectively re-imagine or culturally re-member the events of the Banana Massacre and the destructive fallout.

The Presence and Power of the United Fruit Company in Colombia as well as throughout Latin America

The consumer popularity of the banana is directly related to the rise of the “banana republic” and the international success of the UFC, which formed a close bond with the burgeoning imperialist reach of the US by the turn of the twentieth century. As Peter Chapman states in Bananas: How the United Fruit Company Shaped the World (2007):

United Fruit’s business was bananas. From bananas it had built an empire. The small states of Central America to the south of the US had come to be known as the “banana republics”: Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama. United Fruit’s reach extended to Belize—former British Honduras—and to Caribbean islands such as Jamaica and Cuba. In South America, Colombia and Ecuador had come under its sway. A company more powerful than many nation states, it was a law unto itself and accustomed to regarding the republics as its private fiefdom (1-2).1

Throughout Latin America, and for the greater part of the twentieth century, the UFC held a monopoly on banana plantations and production (Figure 1). The UFC was an early example of the modern transnational corporation, which perfected the system of cash-crop capitalism by taking advantage of the US’ expanding imperialism at the end of the nineteenth century.2 Their practice laid the groundwork for what would evolve over time into the concept of globalization and mass production. This tragedy is just one of many precipitated by the UFC’s presence and involvement in Latin America. Again, Peter Chapman sheds light succinctly in the far-reaching negative impact and political dominance of the UFC:

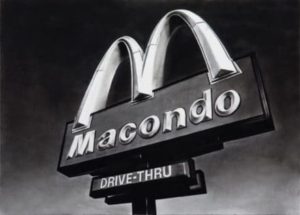

The company’s long history rendered it the ultimate “corporate nasty.” It changed governments when it didn’t like them, like the one in Guatemala [under the democratically elected President Jacobo Arbenz] in 1954 that had wanted to donate some of United Fruit’s unused land to landless peasants. In 1961 United Fruit ships sailed to the Bay of Pigs in Cuba in an effort to overthrow Fidel Castro. As far back as 1928 the company was implicated in the massacre of hundreds of striking workers in Colombia. Gabriel García Márquez had written about the strike in One Hundred Years of Solitude. Born just before the massacre, he had taken the name of his fictional banana zone of “Macondo” from that of a United Fruit plantation near his home in Aracataca (3).

However, many Colombians outside of the Caribbean region did not even know what this massacre was until after 1967, upon the publication of García Márquez’s novel, and almost four decades after the tragedy itself (Figure 2). However, a collective memory kept alive via the Caribbean coast’s oral traditions is responsible for preventing the massacre from being completely forgotten, and indeed for inspiring García Márquez who was raised within that tradition, crediting his grandmother particularly as his most influential raconteur. The fact that García Márquez’s One Hundred Years placed so much attention to the case of the masacre de las bananeras shows how much literature and the recording of history have dually influenced each other.

Indeed, it is imperative to highlight that the masacre de la bananeras of 1928 was not just a regional event unconnected to national politics, but actually one of the first major national tragedies of the twentieth century in Colombia. To understand the unfair practices of the UFC, it is important first to summarize how this corporation was given access to Colombia at the end of the nineteenth century, and how they exploited the weaknesses of a post-colonial territory struggling to find its place within the burgeoning global economy.3 The opportunity for the UFC to manipulate Colombian soil began during the 1890s when Minor C. Keith—the man responsible for creating railway systems in Chile, Perú, and Costa Rica, and, thus, capitalizing on the bananas he had planted with his Tropical Trading and Transport Company—constructed a railway in the Magdalena region of Colombia with the permission of the Colombian Land Company. Taking advantage of this railway, Keith began to export fruit to the US via the Snyder Banana Company of Panama, which was still Colombian territory at the time. In 1899, Keith entered into a deal with Andrew Preston and Dow Baker, owners of the Boston Fruit Company, which were the biggest exporters of bananas from the Caribbean market (mainly Jamaica) at the time. The three men merged their companies on March 30, 1899 and formed the United Fruit Company. That year, the UFC, taking advantage of the lack of consolidation that had characterized Colombia since 1830 as well as the political instability the country faced during the War of a Thousand Days (1899-1902), entered Colombia and established plantations throughout the Magdalena area (Figure 3).4 Rafael Reyes, the Conservative president who was in power immediately following the War of a Thousand Days, offered incentives to foreign businesses such as the UFC to operate in Colombia and help jump start the country’s economy. The UFC took advantage of Reyes’ offer by purchasing additional land for banana cultivation and expanding the country’s railway systems.

After the War, thousands of soldiers from interior regions, the majority of them Liberal sympathizers, migrated to the Magdalena region in search of work and soon became part of the banana industry’s labor force. UFC dominance and US imperialism seemed to be working hand-in-hand.5 The UFC’s unfair labor practices began first with their hiring of banana plantation workers via subcontractors, thus creating distant relations between the company and the actual labor. In addition to a lack of recognition as official UFC workers, the company paid these sub-contracted laborers with vouchers and tokens that could be used in UFC-run stores in and around the banana-producing zone. By the opening decades of the twentieth century a type of neo-slavery of plantation labor was fully in effect a little more than five decades after the abolition of chattel slavery in Colombia in 1851.

In January of 1928 several union leaders from Colombia joined together to focus on the particular situation of the Magdalena workers. In November of that year 32,000 workers went on strike when Thomas Bradshaw, UFC company manager, refused to negotiate with them. Bradshaw argued that he had no obligation to bargain with the union, since technically they were not official UFC workers. This, of course, was a loophole that refers back to the workers’ original frustrations: since subcontractors were hiring them indirectly, they had distant relations with the directors of the UFC. The UFC approached the government to allow them to hire strikebreakers to cut the bananas, a plan that they not only allowed, but also supported by offering the army to help in the endeavor. The first trainload of this fruit cut by strikebreakers and soldiers arrived in Santa Marta on December 4. When news of this reached the union members, they decided to gather in Ciénaga’s main plaza on December 5 to protest this unfair substitution and demand again that the UFC recognize their petitions. Throughout the course of the day, as hundreds of people gathered in the plaza waiting for the UFC company manager to appear and negotiate, General Carlos Cortés, leader of the Colombian army, dispatched his troops to the area. The crowd became discouraged upon learning that neither Thomas Bradshaw nor any UFC representative would appear. Cortés ordered the demonstrators to disperse by 11 p.m.; they refused and at midnight Cortés ordered the troops to open fire. What ensued is the act for which the UFC is most infamously known in Colombia: the killing of an unidentified number of unarmed striking laborers, who were then discarded in an undetermined area. The event was branded as the masacre de las bananeras. Almost an entire century after the tragedy, one single question remains: How many victims resulted from this fatal encounter?6

Indeed, the importance of García Márquez’s fictional account for bringing the tragedy to light cannot be understated. The 1991 documentary My Macondo directed by Dan Weldon was probably the last attempt in the twentieth century to find out exactly how many people died on the fatal night of December 6, 1928 and what, if any, information could be provided by the aging witnesses of the tragedy. Led by the late Colombian journalist Julio Roca, My Macondo, is a “search for Macondo” so to speak, in that Roca researches any available print versions of the tragedy from and around the date of December 6, 1928. He interviews surviving witnesses of not only the protest, but the actions of the UFC in the region. He follows this with interviews of managers of the UFC banana plantations of the day, which by that time, had evolved into the aforementioned Chiquita Brands, Inc. But the most noteworthy part of the documentary is the interview with García Márquez at his home in Mexico where he talks about the event that he had heard about all of his life. In the interview, García Márquez claims that during his writing of One Hundred Years in the mid 1960s, he inflated the number of victims for narrative purposes. According to García Márquez, in reality there were only seven at most casualties, but that in order to fit the exaggerated dimensions and narrative style of the book that he was writing, a figure such as 3,000 casualties would make more sense.

…The banana events—García Márquez said—are perhaps my earliest memory. They were so legendary that when I wrote One Hundred Years I wanted to know the real facts and the true number of deaths. There was a talk of a massacre, an apocalyptic massacre. Nothing is sure, but there can’t have been many deaths. But even three or five deaths in those circumstances at that time…would have been a great catastrophe. It was a problem for me…when I discovered it wasn’t a spectacular slaughter. In a book where things are magnified, like One Hundred Years of Solitude…I needed to fill a whole railway with corpses. I couldn’t stick to historical reality. I couldn’t say they were three, or seven, or 17 deaths. They wouldn’t even fill a tiny wagon. So, I decided on 3,000 dead because that filled the dimension of the book I was writing. The legend has now been adopted as history (Posada Carbó translation of García Márquez, 395-396).7

Historian Eduardo Posada Carbó’s article “Fiction as History: The Bananeras and Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude” (1998) takes this interview by García Márquez as his point of departure, grappling with the question of written history versus oral traditions: “Two contradictory legends and two contradictory versions of history popularized by the work of a novelist; does it matter?” (396). No one would argue against what García Márquez states: that until the discussion of this catastrophe in One Hundred Years, the history of the event had been kept under wraps on a grand scale and that outside of Colombia the events surrounding the banana workers were relatively unknown. Posada-Carbó’s study highlights that García Márquez’s figures of the victims of the massacre have been taken as fact, since previously, in interviews around the time of the 1967 publication of One Hundred Years, García Márquez would indeed claim numbers in the thousands.8

In spite of the bloody history of the UFC in Colombia (or perhaps because of it), the corporation continued to operate on Colombian soil. At the time of the banana massacre, the UFC was already valued at over $100 million.9 The past few years have exposed how the company made extortion payments to the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) rebel group from the 1980s through the 1990s for use of land in the Urabá region, just south of Panamá, and that from 1997 to 2004 the Chiquita group paid the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC, the main paramilitary group in Colombia) $1.7 million to protect their land from guerrilla groups as well as to ensure their presence there. This is in spite of the fact that in 2001 the US government identified AUC as a ‘terrorist’ organization. Fernando Aguirre, the CEO of Chiquita, admits to this strategy as well as the payments to FARC during the 1980s and 1990s in a May 2008 interview on CBS’s 60 Minutes: “The Price of Bananas” directed by Steve Kroft. In 2007, Chiquita agreed to pay a $25 million fine for these violations.

Within these unethical and imperialist practices, the larger question remains: why were banana plantation workers not recognized officially by the UFC, either when they initially sought recognition or in the aftermath of the tragedy, as victims of neo-colonialist and imperialist violence? There can be no doubt that in such a racially diverse country as Colombia, that the striking workers in 1928 on the Caribbean coast of Colombia were part of black, indigenous, and mixed-race communities. Specifically, these were and continue to be racialized bodies discarded in the oblivion of history, forever remaining unaccounted for. Therefore, if official history rejected these racialized bodies, whose insignificance was compounded by their poverty and low social class, then it goes to say that these victims’ lives were officially deemed as undeserving of recognition. Within this context lies the attempt of the four artists—writers and visual artists—who throughout the past five decades sought to maintain this tragedy in the collective memory of Colombia and pay homage to each of the individual lives taken and disregarded on December 6, 1928.

The Legacy of Gabriel García Márquez and One Hundred Years of Solitude in the Colombian Caribbean

Less than thirty-five years after the success of One Hundred Years of Solitude, García Márquez’s highly awaited 2002 memoir Living to Tell the Tale explicitly discussed how the “banana company” left an indelible mark on his childhood, as the haunting memory of the strike caused deep trauma for the region’s inhabitants and changed the societal landscape of the area. As an adult, García Márquez searched for answers amongst those that witnessed the events:

…I spoke with survivors and witnesses and searched through newspaper archives and official documents, and I realized that the truth did not lie anywhere. Conformists said, in effect, that there had been no deaths. Those at the other extreme affirmed without a quaver in their voices that there had been more than a hundred, that they had been seen bleeding to death on the square, and that they were carried away in a freight train to be tossed into the ocean like rejected bananas. And so my version was lost forever at some improbable point between the two extremes. But it was so persistent that in one of my novels I referred to the massacre with all the precision and horror that I had brought for years to its incubation in my imagination. This was why I kept the number of dead at three thousand in order to preserve the epic proportions of the drama, and in the end real life did me justice: not long ago, on one of the anniversaries of the tragedy, the speaker of the moment in the Senate asked for a minute of silence in memory of the three thousand anonymous martyrs sacrificed by the forces of law and order.

The massacre of the banana workers was the culmination of others that had occurred earlier, but with the added argument that the leaders were marked as Communists, and perhaps they were. I happened to meet the most prominent and persecuted of them, Eduardo Mahecha, in the Modelo Prison in Barranquilla at about the time I went with my mother to sell the house, and I maintained a warm friendship with him after I introduced myself as the grandson of Nicolás Márquez. It was he who revealed to me that my grandfather was not neutral but had been a mediator in the 1928 strike, and he considered him a just man. So that he rounded out the idea I always had of the massacre, and I formed a more objective conception of the social conflict. The only discrepancy among everyone’s memories concerned the number of dead, which in any event will not be the only unknown quantity in our history (emphasis added, 68-69).

Whether the figure is in the single digits, the hundreds or the thousands, what is important about this quote by García Márquez is that it demonstrates an early understanding of the disregarding of bodies if not whole communities of people, in particular by his symbolic comparison: “tossed into the ocean like rejected bananas” and the conviction that the tragedy of the UFC workers was neither the first nor the last unknown quantity of victims within Colombia’s history of violence. The Macondo created by García Márquez in One Hundred Years thus served symbolically as a representation of Ciénaga, the Caribbean’s contentious history tied to banana cultivation, and Colombia’s position in the larger context of the new order of US imperialism in Latin America that began with the close of the nineteenth century. But what was it about Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years, and the publication year 1967 that all worked together to bring this history to light on an international level?

García Márquez had deep ties to bananas. The author was born on March 6, 1927 or 1928, in the banana region of Colombia, in the small town of Aracataca, part of the department of Magdalena within the country’s Caribbean region. Emphasizing again the interweaving of fiction and history, it is possible that the novelist’s disputed birthdate became associated—either by himself or by the readers of his many works of fiction—with 1928 in order to place the date of his birth in the same year as the fatal events, thus creating a metaphoric bond between the writer and the history of the Caribbean. Although trained as a journalist, García Márquez became known worldwide for his many highly acclaimed and best-selling works of fiction, including novels, novellas and short story collections. There is no doubt that the publication of One Hundred Years in 1967 by Buenos Aires-based Sudamericana Press thrust him onto the worldwide literary scene. One Hundred Years garnered many prestigious literary awards, such as France’s Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger (Best Foreign Book Prize) in 1969, Venezuela’s Rómulo Gallegos Award in Literature in 1972, and of course helped “Gabo”—as he is affectionately called by readers around the globe—secure the 1982 Nobel Prize for Literature. Since its publication more than half a century ago, One Hundred Years has sold more than 45 million copies (Santana Acuña, 2017).

The global historic events surrounding the late 1960s, indeed, solidified this novel’s presence for the decades that followed and our continued interest in this work today.10 One Hundred Years was the culmination of the so-called Latin American “boom era,” a decade in which international focus on the continent coalesced following the Cuban Revolution of 1959. Writers from all over Latin America were given overdue attention within global markets, hence the coining of the terms “boom era” and “boom novels” due to editorial houses’ desire for translated editions of what would become canonical novels that narrated a mid-century landscape with a historical and social consciousness at the forefront of their storylines. Although also insuring the hegemony of patriarchal cultural dominance (the most widely recognized novels of the boom were all written by men), the existence of the Latin American nueva novela confirmed the move away from realism as these “boom novels” were considered narratively groundbreaking for the time.

Thus, the close of the decade with a new revolutionary consciousness for Latin America was perfect timing for García Márquez. As Alvaro Santana Acuña (2017) discusses, García Márquez’s novel came in a year when Guatemala’s Miguel Angel Asturias won the 1967 Nobel Prize for literature, cementing indeed the range of successes for Latin American fiction writers. It is important to note that Asturias’s accomplishments were not merely coincidental for García Márquez. Recognized as a precursor to the “boom era” of the 1960s, Asturias’s narrative style in such works as El señor Presidente (1946, English title: The President) and Hombres de maíz (1949, English title: Men of Maize) are also associated with magical realism. Coincidentally, or perhaps not so, three other major works of Asturias are considered “The Banana Trilogy”: Viento fuerte (1949), El papa verde (1953) and Los ojos de los enterrados (1960) chronicle the forced entrance and stronghold of the UFC into Guatemala, and the US backed coup against democratically elected Jacobo Árbenz in 1954.

Within García Márquez’s own banana saga, the twenty-chapter account of the Buendía family that comprises One Hundred Years metaphorically narrates the history of Colombia, from the pre-conquest, to the colonialist, and later post-colonialist eras by way of the foundation of Macondo. The grandiosity of the Buendía story is epic in nature and considered by critics as almost biblical in scale. The origin of the Buendía family at the beginning of the nineteenth century is a take on the creation of the Colombian nation after its independence from Spain in 1823, and also on the Caribbean Colombian community as pivotal to national ethnicity and culture. One of the many appealing aspects of the novel is that memory takes center stage in One Hundred Years, serving to contest official history. In effect, the repeated tragic and violent events that comprise the chapters of the novel are parallel to the repetitions of Colombia’s turbulent history and the social conditions that particularly impact communities of people marginalized by race, gender, and class.

The narration of One Hundred Years initiates with Colonel Aureliano Buendía’s memory of his childhood, from which the reader then travels in time towards the foundation of Macondo. From that moment on, memory is emphasized as a main protagonist within the novel, becoming the center point with which to associate the banana massacre to subsequent Buendía generations.11 Progress is another leitmotiv of the novel and arrives at the village by way of the arrival of the banana company. Ironically, this will spiral Macondo into the destruction that will cause the fulfillment of Melquiades’s manuscript. Melquiades—described as a “wandering gypsy” throughout the novel—is the most important character outside of the Buendía clan, as he introduces Macondo to such magical elements as alchemy and flying carpets. In sync with this magical realist description, a plague of insomnia is introduced in chapter three, which causes the erasure of memory of the entire town. The insomnia serves as a foreshadowing of the tragic and landscape-altering events that would eventually unfold as the decades go by in Macondo. Linking to the previous historical outline of the events that led up to the massacre, and their subsequent “erasure” from history, a reader with an understanding of Colombian history recognizes the substantial symbolism planted from the beginning chapters of García Márquez’s magnum opus. In this respect, García Márquez orchestrates an invitation for rememory as a collective project where the reader witnesses the remembering of events.

The name that García Márquez created for the village at the center of the Buendía tale—“Macondo”—is in itself noteworthy for its connection with bananas. Macondo was modeled after Aracataca, the sleepy town of García Márquez’s youth. He recounts in his aforementioned 2002 memoir that as a child, he saw the word “Macondo” for the first time on a sign noting the name of a banana plantation near Aracataca (21), finding out later on in his career as a journalist that the word meant the name of a wandering people in Tanzania.12 If Aracataca is indeed the “the sleepy town” that inspired the creation of his Macondo, the nucleus of One Hundred Years’ Buendía family, it was also the appropriate setting for the place that was invaded by the “banana fever” brought in by the foreign company described in the narration.

The arrival of Mr. Herbert to Macondo, and his amazement with bananas, changes the course of the novel. Mr. Herbert’s astonishment upon first “discovering” the banana emphasizes the exoticism of the fruit for the foreigners:

Then he [Mr. Herbert] took a small case with optical instruments out of the toolbox that he always carried with him. With the suspicious attention of a diamond merchant he examined the banana meticulously, dissecting it with a special scalpel, weighing the pieces on a pharmacist’s scale, and calculating its breadth with a gunsmith’s calipers (225).

The attraction of this strange product—the banana—to outsiders is the pivotal moment that changes the landscape of Macondo. Next a group of “engineers, agronomists, hydrologists, topographers, and surveyors” (226) swiftly invades Macondo, followed by Mr. Jack Brown, president of the banana company, and a group of other executives, lawyers, and the wives of all these “Yankees.” Macondo soon became transformed by the “gringos” from the sleepy town to a place lined with “wooden houses with zinc roofs inhabited by foreigners who arrived on the train from halfway around the world” (226). Commenting clearly on the history of the UFC and US imperialism, García Márquez lays bare the powers that will eventually cause violence in a once peaceful region:

When the banana company arrived, however, the local functionaries were replaced by dictatorial foreigners whom Mr. Brown brought to live in the electrified chicken yard so that they could enjoy, as he explained it, the dignity that their status warranted and so that they would not suffer from the heat and the mosquitoes and the countless discomforts and privations of the town. The old policemen were replaced by hired assassins with machetes (237).

In the larger scope of the novel, these forces eventually bring forth the downfall of the Buendía family, in particular of Colonel Aureliano Buendía.

While García Márquez sets forth the exoticism with which the foreign banana company arrives in and perceives Macondo in the humorously exaggerative tone for which he is most widely known, the section of One Hundred Years primarily inspired by historical events addresses the ten-year-long UFC workers’ strike. The banana workers, after being led around in circles by the company, organize a strike. García Márquez interlaces his narration inspired by the events described in the historical section above within the family saga of the Buendías: the narration refers to the actual General Carlos Cortés Vargas who, during the union members’ meeting in the plaza tells the gathered crowd that they have five minutes to disperse. The young José Arcadio Buendía shouts to Cortés Vargas: “You bastards!…Take the extra minute and stick it up your ass!” The General, in turn, gives the order to fire (305). The narration follows Arcadio Segundo’s awakening amidst a pile of bodies on a train headed for the sea and concludes with him insisting on his death bed, “[T]here were more than three thousand of them….I’m sure now that they were everybody who had been at the station” (313).

Arcadio Segundo’s conviction that the victims not be forgotten serves as the literary recording of what García Márquez and many others in the Caribbean region of Colombia kept alive via their oral history for decades: the tragedy that occurred in Ciénaga on the fatal night of December 6, 1928. At the same time, this narration emphasizes the lack of recorded and official history. The inhabitants of Macondo were aware of their need to make sure that this tragedy would not be lost into oblivion for subsequent generations, as most certainly it would not be accounted for officially. Ironically, though, this oral narrative style has been (mis)interpreted endlessly as “magical realism.” Regarding this, Raymond Williams (1991) says: “What has often been identified by the now overused and frequently vague term magical realism in this novel is more precisely described as a written expression of the shift from orality to various stages of literacy. The effects of the interplay between oral and writing culture are multiple” (120). In effect, “magical realism” continues to be an overused term created by institutions outside of Latin America, not only for marketing purposes, but also as a way to simplify the deployment of oral culture and tradition in literature. García Márquez’s deadpan style was inspired by his own grandmother’s knack for storytelling, and falls squarely within an oral tradition closely associated with the Caribbean and many diasporic African communities, which had been historically barred from recording their histories, traditions, and folkloric practices via written documents. García Márquez’s oral narrative technique can also be said to have been influenced by his activity in the Colombian Caribbean literary circle, the Grupo de Barranquilla, which, during the 1950s challenged the standard and realist narrative methods of the country’s literary establishment, and from which they were trying to liberate themselves.13 One of the primary ways that García Márquez became associated with so-called magical realism was that in his take on the oral story tradition, recountings of events became so exaggerated that the preposterous nature and ridiculous circumstances surrounding story details narrated in a type of humdrum, nothing-out-of-the-ordinary matter turned the pages of One Hundred Years into the subtle humor for which his stories were known. What would be seen as monumental, fantastic, or uncanny against a different narrative format is detailed as though an everyday occurrence.14 Because One Hundred Years is completely full of exaggerated narrative instances, this novel became associated with the example of “magical realism” par excellence.

So, what does deeming this novel as “magical realist” mean for the victims of the only non-fictional story-line, namely the workers killed in the Ciénaga banana massacre of 1928? One Hundred Years has been praised as having brought to light this massacre, but on the other hand being associated with so-called “magical realism,” one can argue, diminishes the actual history that inspired the epic story of the Buendía clan and the rise and fall of Macondo that sits at the center of the novel. Macondo is literally not on the map; the ability to turn a blind eye to a people and a region did not just occur after the banana plantation workers were killed. It can be argued that this indeed was how the UFC chose the sleepy towns in the late nineteenth century for banana cultivation: they were primarily underdeveloped areas whose land and people could be exploited. The notion of solitude alluded to in the novel thus reiterates this crime’s never having been recognized officially by the state and how we will never know the actual number of victims, emphasizing the marginalization of this area of Colombia and its people.

Carlos Arturo Truque and the Representation of Everyday Violence and Exploitation

Given the worldwide sensation surrounding One Hundred Years upon its release as well as its continued canonical status in contemporary times, it is unfortunate that so many other authors who also interpreted the Ciénaga tragedy in diverse ways fell under the shadow of García Márquez’s fame. Contemporaneous to other writers in Colombia who chronicled the country’s tragic history of violence was a generation of prose writers of Afro-Colombian descent such as Arnoldo Palacios (1924-2015), Manuel Zapata Olivella (1920-2005), and Carlos Arturo Truque (1927-1970). They also took on the topic of violence throughout Colombia, yet they emphasized geographically and culturally marginalized areas of the country, such as the Afro-Colombian communities of the Caribbean and Pacific regions.

Truque’s posthumously published short story “El encuentro” (“The Encounter,” 1973) similarly drew attention to the often violent exploitation of Colombia’s labor force. The most revealing aspect of this short story, however, is Truque’s reference to the masacre de las bananeras. Although appearing only a few years after the publication of the most celebrated depiction of this same tragic event in Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years, it is possible that Truque’s story was indeed written simultaneously to, or even before García Márquez penned the Macondonian account. The depiction of events surrounding the workers’ plight as seen in “El encuentro” represents the previously discussed transitional literature that surfaced in the second half of the twentieth century, just as a new wave of innovative Colombian writers (including García Márquez and Truque, as well as the aforementioned Palacios and Zapata Olivella) challenged not only the orthodox confinement of the nation’s literary output, but also the cultural, thematic, and racial dominance of the country’s center-Andean region. Unfortunately, the categorization of Truque as a short story writer with an inclination towards an Afro-Colombian consciousness in his works has rendered his contribution to Colombia’s representations of this tragedy widely unexplored within literary criticism. Truque’s “El encuentro” explores a point of view that had not been examined previously: the Afro-Colombian narrative on violence tied to banana cultivation and transnational exploitation in the Caribbean. Truque’s “El encuentro” thus represents one of the few examples of the literary relationship between race, class, and violence of the masacre de las bananeras.

Truque was born in 1927 in Condotó, in the department of Chocó, Colombia. His father, Sergio Isaac Truque Müeller, was of German heritage and his mother, Luisa Asprilla, was Afro-Colombian. Shortly after his birth, the family moved south to the city of Buenaventura, in the department of the Valle del Cauca and closer to Cali, one of Colombia’s major cities. This move provided the Truque-Asprilla family with more educational and professional opportunities than those available to them previously. Although his father was a staunch conservative who preferred more stable careers for his children, the younger Truque eventually chose, against the older Truque’s demands, to pursue a career in writing. He began his career contributing various articles, book reviews, and poetry to the newspaper El Liberal. Some of Truque’s first literary recognitions began in the early 1950s, including a 1953 award for his short story “Vivan los compañeros” (published in Tres cuentos colombianos alongside stories by García Márquez and Guillermo Ruiz Rivas). In 1964 he suffered a stroke that left him unable to work. Supported by friends and family, however, he continued to produce short stories during the last few years of his life. He died in Buenaventura in 1970 at the age of 42. Three years later, due to the efforts of his wife Nelly, the Colombian Ministry of Education published the collection El día que terminó el verano y otros cuentos. This assemblage of Truque’s short stories includes some previously published works as well as unpublished stories, including “El encuentro.”

“El encuentro” is a glimpse into the life of an individual family afflicted by the exploitation of the factory, a symbol of modern progress which has served, for decades, as the only labor opportunity available for the anonymous town’s inhabitants. A modest house in the town provides the backdrop for a short scene involving two protagonists: Alonso and his wife María. Alonso works at the local factory, but recently his hours of labor have been reduced and he finds himself bringing less and less money into the household. Ambrosio, the union leader, although not appearing physically in the one-scene story, is described as having a strong influence on the socialist leanings of Alonso, much to the dismay of María. For María, Alonso’s involvement with the union makes no sense, given that Ambrosio’s children were suffering just as much as theirs: “they went about…with their butts out, without a thread to put on” / “andaban…con las nalgas afuera, sin una mecha que ponerse” (112). Even more, according to María, Ambrosio’s leadership in union endeavors was based on “pure laziness, to not work and [instead] look for the workers to talk to them about the damned union” / “pura pereza, por no trabajar y andar en busca de los de la fábrica para hablarles de su maldito sindicato” (112).

The factory itself plays a major and dual role in the story. First, this space of industrial innovation functions as a root cause of Alonso and María’s anguish as a couple. Apart from Alonso’s scarce pay, which results in his family’s hunger and constant financial uncertainty, María complains that the nearby factory produces continuous dirt and dust in the house, thereby emphasizing its presence and stronghold over the town, as well as its unceasing metaphorical existence within the domestic sphere. Secondly, the factory effectively controls their fate, just as it has that of other families in the town for generations. The nature of its existence and violence is cyclical. The narrator stresses the parallel between the current conditions and those that both Alonso’s and María’s fathers experienced as workers in the factory decades prior: “That was what the strike of 28 was about for María. A dead worker, a red flag, a bunch of drunks, and young Alonso, serious and solemn, forced to be a man by an order of life” / “Eso fue para María la huelga del 28. Un obrero muerto, una bandera roja, muchos borrachos, y Alonso niño, grave y solemne, empezando a ser hombre por un mandato de la vida” (114). María, like Alonso, experienced the original strike as the child of one of its workers; the Ciénaga tragedy is referenced by way of the “strike of 28” / “huelga del 28” when both were merely youngsters unable to understand the struggle between the UFC and those they exploited.

What “the factory” produces is left ambiguous by Truque. However, it is important to note that whether it be a factory of advanced industrialization or a plantation of bananas, this symbol of innovation still serves to reemphasize the imperialist and neo-colonialist economic reality of the region. Although alluding to the great strike of 1928, Truque discusses a factory that brings in dust and dirt to the inhabitants, as a foreign invasion whose product is not native to the soil where it is produced, like bananas.15 Nevertheless, the emphasis is that, similar to the UFC on the Caribbean coast, their monopoly on agriculture in specific or industry in general rendered citizens vulnerable and economically dependent on their presence. Their presence indeed reinforces exploitation and violence, and in the case of the depiction of everyday life offered by Truque, an understanding that hunger is an unavoidable aspect of the domestic space.

In his critical analysis of this scarce economic security that the capitalist edifice provides, Marvin A. Lewis (1987) says:

María, his wife, constantly reminds him [Alonso] that a little bit of something is more than a whole lot of nothing….The dichotomy in “The Encounter” is between the economic security the factory could provide and the abject poverty in which the workers live and from which they wish to break (56).

In effect, the story confirms the cyclical nature of historical violence: the final scene has María remembering the outcome of the strike of 1928, as she feels “strangely united to a past that she did not want repeated”/ “unida extrañamente a un pasado que no quería que se repitiera” (119). Alonso’s choice in following Ambrosio and the crowd joining the strike instead of the whistle of the factory (in spite of María’s pleas to go work instead of giving money to the union) confirms the repetition of history that will ensue. Alonso’s death is imminent upon his leaving, as the narrator describes how the scene corresponds to a final goodbye: “She no longer saw or felt him, he was forgotten as he was and submerged, outside of himself, clean and won over by that strong and welcoming wave” / “Ya no la veía, ya no la sentía, olvidado como estaba y sumergido, fuera de sí, limpio, ganado por esa corriente tierna y poderosa” (120). The reference to the undeniable pull of the strike, and the ensuing encounter with the masses could very well be an encounter with his own death, and a parallel to his father’s demise decades prior.

The notion of the “encounter” that the title suggests can lead us to various interpretations of the encuentro itself. The first and only literal encounter during the story is between Alonso and María. But the ultimate encounter is that of Alonso with his future, as he leaves the house against María’s wishes to confirm his solidarity with Ambrosio and the union cause. His departure will ultimately result in the repetition of historical violence, tied directly to the 1928 events surrounding the banana plantation laborers. In general, Truque’s work stays faithful to detailed descriptions of those suffering under transnational exploitation. He highlights these basic elements of survival in congruence with marginalized communities, in particular with Afro-Colombians who have historically represented a large portion of this class struggle between the worker and the factory. Truque’s literary technique in these detailed yet short descriptions forfeits both the exaggerative and experimental styles, each of which was in vogue throughout the middle decades of the twentieth century. Thus, various instances detailed meticulously by Truque lead to the final, crucial moment of “El encuentro.” But it is one particular moment—the very act of Alonso’s leaving the house—which causes a rift in the cyclical nature of his life with María and their unbinding connection to the factory. Yet, whatever the outcome of Alonso’s action, he and María will remain tied intrinsically to the factory’s control. Alonso’s attempt to break from the confinement perpetuated by the factory’s control of the town for generations is comparable to Truque’s political viewpoints as an Afro-Colombian writer.

Lewis explains the intertwining of race and class as core elements of which authors such as Truque, Palacios, and Zapata Olivella have been historically conscious:

The word Afro-Colombian is used in this study to suggest that these writers recognize the importance of their ethnic backgrounds in the development of their literary creations and in the manner in which they relate to Colombian society. They are faced with the task of writing both as Colombians and as blacks. This creates a unique problem of duality of perspective since they cannot separate the situation of poor blacks from that of the majority of destitute Colombians. Therefore, the issue in the literature becomes one of balancing class/caste against ethnicity, with the realization by the authors that, for Afro-Colombians, the class problem is compounded by one of color (2).

Precisely, therefore, we see how the class struggle present in Truque’s work is also inherently tied to ethnic and racial marginalization in Colombia. The boundaries that slavery imposed have historically victimized Afro-Colombians within racist systemic practices, such as lack of access to both education and alternative opportunities for employment. Transnational corporations such as the UFC had been exploiting these conditions for almost a century by the time “El encuentro” was published, and Truque’s work, both in narratives and essays, showcase this injustice. His narrations indicate to us the strategic and careful way in which Truque discussed violence in “El encuentro” and related the overall feeling of instability in the household and the town. Brought on by both class and racial hierarchies, this subordinate position proves to be a manifestation of the continuation of a subtler, institutionalized and, thus, more dangerous violence. In spite of the fact that “El encuentro” provides a very subtle reference to the events of December 6, 1928, Truque’s identification with the tragedy in Ciénaga allows for a larger discussion on how class and racial divisions in Colombia, particularly in the Caribbean region, enabled the UFC to take advantage of economic and social disparities which resulted in hunger and lack of alternative job opportunities.

“El encuentro” represents the complex relationship between three factors and outlines how both national and social conditions are, in fact, interrelated: Truque adopts the premises of race, class, and violence as themes in his prose to demonstrate how such factors have historically contributed to the subordinate position of the Afro-Colombian community. We believe that it is for these aspects that his focus on the 1928 violence against the bananeros in the Caribbean has been largely ignored and uncategorized within the breadth of literary interpretations of this event. Furthermore, Truque’s fiction is also significant as he was part of a generation of writers who contributed to the shift in Colombia’s literary focus to subject matters that encompassed marginalized communities and geographic regions. His exploration vis-à-vis short stories includes a discussion of class and ethnic marginalization throughout Colombia specifically, and the Caribbean more broadly. As such, his story points to the way in which racialized identity markers have been consistently marginalized from inclusion in Colombia’s national consciousness. García Márquez and Truque are just two of Colombia’s many writers who have recounted the tragedy of the Banana Massacre via literature in diverse ways and to varying degrees. Rememory, then, serves as an analytical tool, placed at the crossroads between fiction and non-fiction, memory and erasure within the national historical conscience.

The Contemporary Scene: Colombian Visual Artists Represent the Cultural and Political Importance of the Banana

Though the presence of the UFC provided much fodder for Latin American authors, it is the performativity of bananas that have produced enduring icons within popular culture. Through artistic performance we are able to witness how visual culture employs rememory as a way to address a difficult shared history. These visual and performative registers which re-enact the banana body/black body supposition have been sustained over the past 150 years.

Liliana Angulo Cortés and the Performance of the Banana

One of the most common tropes of the banana is its comedic aspect, which can be traced as far back as the 1870s.16 The humorous power of the banana can be located in filmic representations as widespread a Charlie Chaplin’s pratfalls in The Pilgrim (1923) to the zany sexual innuendos such as the “banana in the tailpipe” reference from Eddie Murphy’s Beverly Hills Cop (1984). Liliana Angulo Cortés’s (b. Colombia, 1974) photographic series of 2001, Negro Utópico (Utopic Negro), features nine digital print photographs, 15.7 inches by 23.6 inches, in what, at first glance, appears to be a series of comedic gestures that continue the tradition of “banana as comedic reference.” Negro Utópico focuses on the relationships between the banana, the black body, consumption, and the renegotiation of Afro-Colombian subjectivity both historically and in the current globalized atmosphere.

Angulo Cortés is a mixed media artist working in photography, installation, video, performance, sculpture, and sound. Her Afro-Colombian identity informs her critical conscious and socio-cultural engagement in her performances. After graduating from the National University in Bogotá where she specialized in sculpture, she began developing more performance-related works that explored issues of Afro-Colombian identity, mapping colonial legacies, and problematizing perceptions of gender and beauty. Angulo Cortés’s Negro Utópico is a case study into the projection of colonial desire and the renegotiation of racial fetish by using food as a sign system.

To this extent, Roland Barthes’s article, “Toward a Psychosociology of Contemporary Food Consumption” (2008), in which he argues that food is not just a nutritional substance but also a complex sign system of communication, is applicable to this interpretation of Angulo Cortés’s unique artistic consciousness. Noting that food and its consumption encompasses a body of discrete images, attitudes, protocols of usages, situations, and behaviors, he semantically decodes the “spirit” of food in order to reconstruct its systems and syntaxes. Through a brief examination of the methods and techniques of advertising, Barthes describes the ways in which food has served in commemorating, and communicating, historical events or processes. His theories on masculinized and feminized foods, in particular, are given greater contextual currency when considering the phallic associations with bananas, which is explored in the work of both Angulo Cortés and Gonzalo Fuenmayor.

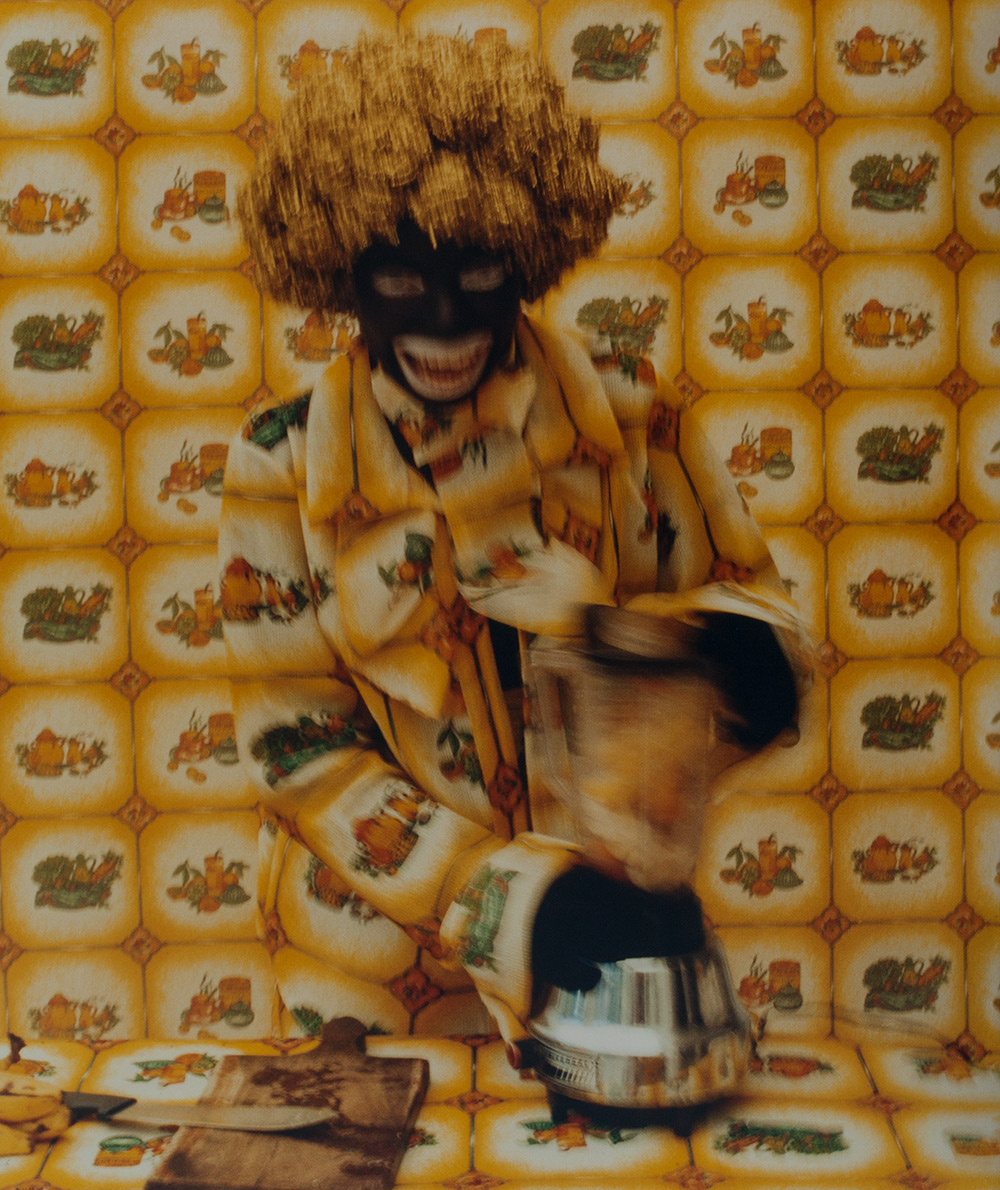

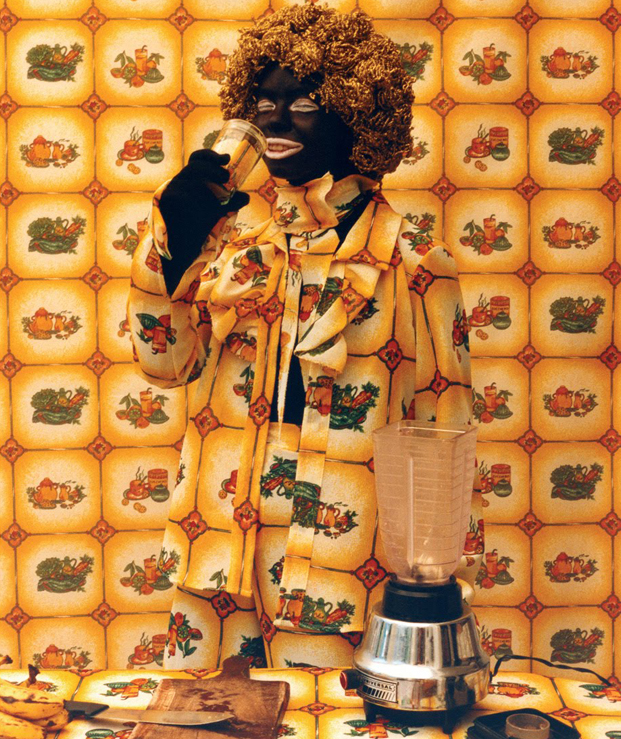

The Negro Utópico series features Angulo Cortés heavily painted in vaudevillian blackface—or in the aesthetic of the Cuban teatro bufo—with coal black skin, black gloves, and white-rimmed eyes and mouth to overemphasize exaggerated lips and buckeyes.17 The ambiguously gendered figure alternates wearing two different afro wigs: one of massive dimensions emphasizing the absurd not only through the scale of proportion, but also because of the ludicrous nature of negative stereotypes. Both wigs are made of stainless-steel wool scrubbing pads. The many coils of the stainless steel are a riff on the coils of natural hair, carefully coiffured. The spun-metal cleaning scrubs also remind us that the subject is in a domestic interior space where she is engaged in household labor. One of the photos depicts Angulo Cortés holding a push broom in one hand while tenderly patting her afro with the other hand in a way that stylizes domestic labor as playful and performative, while at the same time commenting on gender roles and traditional standards of beauty historically demanded of the “ama de casa,” or housewife.

In another photograph she appears to strike a disco pose while holding the broom in her left hand and pointing at the sky with her extended right hand. The pose recalls John Travolta’s iconic stance from Saturday Night Fever (1977). However, while Travolta is pointing at the sky with his index finger, Angulo Cortés’s adaptation shows her right hand in the gesture of a pistol aimed at the sky. Her right hand miming a gun invokes a sense of violence contributing to the subversive layers of the mise-en-scène. In these scenes, Angulo Cortés is attired in an oversized leisure suit similar to the style once fashionable in the 1970s with matching pants, jacket, and clownish tie. The subject’s traditionally male attire functions paradoxically with the feminized domestic labor of the scene. The suit is designed in the same 1970s aesthetic, with a banana-yellow kitchen tile print as the wallpaper and ironing board cushion sleeve. Thus, the body and background covered in the same kitchen tile pattern disorients the viewer’s gaze by flattening the picture plane. The viewer’s access to the scene is denied through optical illusion erasing the physical body except for the exaggerated gestures that reference the caricatured vaudevillian acts of black minstrelsy.

In this manner, Angulo Cortés is emphasizing the disappearance of black subjectivity through the mundane acts of domestic labor by rendering the body invisible via repeated patterns. These visually repeated patterns can be understood as repeated behaviors: that is the reiterative negative stereotypes of blackness as buffoonish, servile, and inconsequential comedic wretchedness. Corey Shouse Tourino describes the Negro Utópico series along with Angulo Cortés’s photo series, Mama Negrita (2007), as cannibalizing, in tune with “the social iconography of blacks in Colombia as mammies, servitude, clowns, folklore, sex objects, and noble savages” (233). Tourino’s suggestion recalls the modernist Brazilian anthropophagy movement where the reversal of agency is located in the colonized entity as consumptive entity devouring the body of the colonizer (inclusive of bodies of knowledge.) The Brazilian anthropophagy movement of the early twentieth century was led by artists and authors whose manifesto conceptualized cannibalism as a form of resistance to imperialist forces. Likewise, Angulo Cortés’s performance can be understood as a cannibalization of negative stereotypes.

A discussion of alimentary discourse can also be located in the three photographs of the Negro Utópico series that feature bananas; these images are essentially a step-by-step instruction on how to make a banana smoothie (Figure 5). On the countertop are a few neatly arranged ripened bananas and an open blender with a gleaming chrome base. Angulo Cortés holds a large knife in her right hand, known as una champeta, commonly used by Afro-Colombian fishermen on the Atlantic seaboard.18 She has positioned the knife almost daringly over the banana slices on the wooden cutting board as she is about to add them into the blender. Angulo Cortés directly engages the viewer with a wide smile that seeks to tempt the viewer’s appetite. The second photograph shows an empty cutting board and knife on the countertop while Angulo Cortés secures the lid and base of the activated blender (Figure 6). The image is somewhat blurry, most likely due to Angulo Cortés’s fanatical movements as indicated by her hyper-enthusiastic facial expression. Her energy has been whipped into frenzy by the wild buzzing of the blender. In the third photograph she calmly stands to drink in the fruits of her labor (Figure 7). She raises the glass with her eyes closed and with a toothy grin halts the actual consumption in savory expression. In other words, the photograph only pictures the raising of the glass and not the actual drinking of the smoothie. Her satiated visage quietly anticipates the sweetness of her labor, and the viewer is left almost unsatisfied in a voyeuristic way: the person finishing the series is not able to gain the pleasure of seeing the subject actually drink the product for which they have invested their gaze. In this manner, Angulo Cortés subverts the labor/consumer narrative, reminding us that often those employed in the production of food labor are not able to enjoy the literal fruits of their labor.

If we take up the conflation of the banana body/black body, as well as the banana body/laboring body then what we discover in Angulo Cortés’s banana smoothie photo series is a recipe for the destruction of banana laborers. Furthermore, by liquefying the banana in a smoothie the object is erased. This is similar to the erasure highlighted throughout García Márquez’s novel where the banana becomes an analog of its laborer. The narrator of One Hundred Years states, “he saw the man corpses, woman corpses, child corpses who would be thrown into the sea like reject bananas” (307). Similarly, the disappearance of Angulo Cortés’s body in the photographs takes on more significance as a representation of the deliberate obscuring of not only black subjectivity, but also the banana laborers. Angulo Cortés’s body can also be read as that of a banana laborer as she is cutting and preparing the bananas for consumption, evoking the cutting of the banana plants and packing them for shipping and distribution. The disappearance of Angulo Cortés’s corporeal body into the fabric of the environment is also a reflection of the disappearance of the Banana Massacre from the historical record. Tourino acknowledges these erasures saying, “Afro-Colombian history is largely absent from national public-school curriculum, and until the ratification of the Constitution of 1991 and Law 70 of 1993 Afro-Colombians had no legal status or protection as a separate ethnic or racial group” (231). Angulo Cortés’s bananas can be understood as representative of the vulnerable bodies of those subjected to the machine gun’s violence in Ciénaga in 1928. Her photographs substitute gun violence with the mechanical and visual destruction enacted by the all-metal drive of a powerful blender, as well as her hand gestures simulating firearms. As the title of this series indicates, Negro Utópico, the utopic or ideal presentation of the black body is one that renders invisible domestic and banana plantation laborers in general, and racialized bodies in particular. Her work intersects with rememory as a kind of re-enactment of the systematic destruction of banana laborers resulting in the gratified hunger for eating the Other and the safeguarding of capitalist agro-industrialization.

Gonzalo Fuenmayor: Reversing the Exoticized Trope of Bananas and Bodies

Both Angulo Cortés and Fuenmayor address the visibility and invisibility of bananas, labor, gender, and sexuality by suggesting innuendo and metaphor with the phallic fruit and its comedic past. However, whereas Angulo Cortés utilizes the historical trope of the “zaniness” of banana humor tied to racial stereotypes, Fuenmayor highlights the actual fruit itself and its presence as an exoticized and hyper-sexualized symbol. Some of these performative aspects of bananas were represented in the first half of the last century by the cultural phenomena of Josephine Baker, Carmen Miranda, and Miss Chiquita Banana. In 1944 the UFC decided to put a “face” on the banana with the creation of the “Miss Chiquita” banana character, designed by comic artist Richard Arthur “Dik” Browne (1917-1989) (Figure 8).19 Browne’s inspiration for Miss Chiquita originated after seeing Carmen Miranda’s performance in the 1943 Busby Berkeley musical, The Gang’s All Here (Figure 9). Carmen Miranda’s image of hyperbolic sexuality is represented in the fecundity of fruits in her headdresses and outfits. In the film, Miranda’s bananas and strawberries musical number is the manifestation of Barthes’s associations between food and gendered syntaxes—strawberries as feminine and bananas as masculine. The phallocentric bananas sharing the stage with the ripe strawberries illuminates the fecundity of male sexual desire imposed on the female body by deploying food as a sign system. The photographs and drawings of Fuenmayor play on this relationship of bananas and sexual innuendos, but with far more explicit overtones.

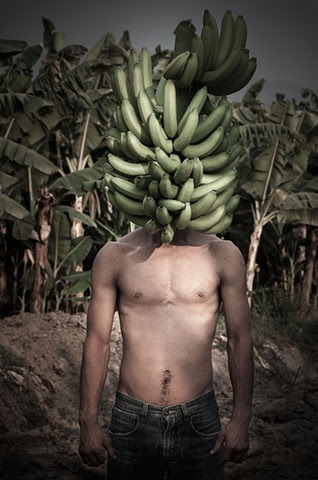

Fuenmayor’s banana performances and works on paper both address the history and rememory of banana labor politics, violence, and the vulnerability of edible masculinities, embodied by the trope of the hypersexualized “Latin lover” as a consumable entity. Born in Barranquilla, Colombia in 1977, the Miami-based artist received his Master of Fine Arts at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. While pursuing his MFA, he began creating large scale works of decaying fruit, palm trees, and Caribbean tropes of tropicalia that were “an act of ‘self-exotization’” (Fuenmayor). What began as a reference to Andy Warhol’s pop art shifted to an exploration of Freudian psychoanalysis and an engagement with the sexual fluency of images. He later included narratives that referenced the history of the UFC in Colombia saying, “It was an anchor that I used to explore several issues that were relevant to me or that I was interested in” (Fuenmayor, 2016). Almost from the beginning, Fuenmayor’s work constituted as a visual examination of a Colombian national past and collective memory.

In particular his Papare series (2013), named after a Colombian banana plantation, comprises 15 photographs averaging 66 inches x 44 inches and featuring a young man in a verdant landscape whose head has been replaced with several hands of bananas reaching over 3 feet in height. Fuenmayor’s vision of the banana plantation as protagonist bears a striking similarity to García Márquez’s personification of Colombia’s history through Macondo.20 For García Márquez, Macondo, as center of the banana company’s plantation, is not just a backdrop to the landscape that is One Hundred Years, but rather, is the landscape of exploitation. The plantation functions as its own character, and becomes a brilliant protagonist whose fate is tied to the destiny of the Buendía family. Likewise, Fuenmayor intertwines the landscape, human labor, and complex subjectivities. In fact, while on an airplane traveling to Colombia, Fuenmayor saw a promotional video that described Colombia as “Magical Realism,” inspired by the marketing strategy and exoticism surrounding García Márquez’s novel. Afterwards, Fuenmayor began thinking about touristic marketing schemes that capitalize on tropical tropes in conversation with the commercialization of large conglomerates such as the fast food restaurant McDonald’s. This strategy is an attempt to realign the minds of potential international tourists away from the decades-long violence that came to a bloody climax with the drug wars of the 1980s and 1990s, in which Pablo Escobar became the metonymic stand-in for the Colombian nation.

Inspired by the ironic marketing of Colombia’s “exoticness,” after returning to the US, Fuenmayor took a picture of the famous golden arches of McDonald’s to study the typeface. In a realistic, black and white charcoal drawing, Fuenmayor captures the renowned logo while changing one key feature: “McDonald’s” becomes “Macondo” (Figure 10). This delicate, almost alliterative difference is enough to conjure the banana republic fictional town of Macondo along with heavily charged political dramas, oral and literary traditions, and the painful memories of past and present. These inflections are also found in Fuenmayor’s Papare series that he describes as,

A body of work that examines ideas of exoticism and the complicit and amnesic relationship between ornamentation and tragedy. Opulent Victorian chandeliers and other elements, reminiscent of a decadent colonial past, proliferate from banana bunches, alluding to a tragic and violent history associated with Banana trade worldwide. I am interested in how ornamentation with its grace and excess has the capacity to camouflage and overshadow questionable circumstance of all kind (Fuenmayor, 2016).

Fuenmayor’s Mister Bananaman from the series is a portrait of a shirtless, slightly muscular young man standing in front of a banana plantation (Figure 11). His low-rise denim pants are tightly fitted descending to just beneath his hip bones. A trail of curly hair leads the eye from his navel directly down to the top of his blue jeans buttons. The verticality of the image also draws the eye upward to the phallic heavy-duty arrangement of bananas on top of his head. In a sense, what is hidden below is mirrored above through a presentation of the phallic bananas indicating a subtle hint as a double-portrait. Fuenmayor is playing with stereotypical tropes of the sexualized Latin lover whose erotic prowess is reflected in the taut poignancy of phallic fruits. However, in a similar strategy presented in Angulo Cortés’s work, Fuenmayor obscures the identity of the subject by replacing the most identifiable part of the body, the face, with hands of bananas. At the same time, the face in itself is decorated with more bananas on top, playing with the “banana headdress” popularized by both the Chiquita Banana and Carmen Miranda imageries. Essentially, the subject becomes the phallic symbol presented as a sexualized object for consumption.

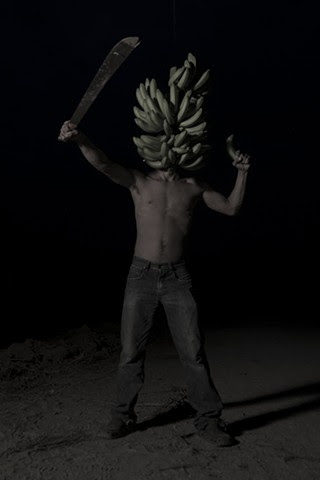

In Los Encantos de la Violencia #1, (The Charms of Violence), the same Bananaman figure is standing on a dirt pathway wrapped in the darkness of night (Figure 12). He is armed with a large machete in his right hand and a singular banana, (what is referred to as a ‘finger’), in his left hand. Although his facial expression is concealed by the large hands of bananas, his wide-legged stance and body language are in vehement protest as he raises the machete to the night sky and flexes his left arm. The scene is dramatically lit from the left and casts shadows on the ground while outlining the figure in dangerous uncertainty. Reminiscent of film noir and surrealism, there is a dreamy texture to these works. A direct comparison between Fuenmayor’s Papare portraits and Belgian surrealist artist René Magritte’s Son of Man (1964) supports the dreamy, fanciful qualities of the Papare series. Perhaps one of Magritte’s most famous paintings, Son of Man, features a man dressed in a dark grey overcoat, red tie, and bowler hat standing before a sea and foreboding sky. His face is mostly obscured by a large floating green apple (Figure 13). Magritte referred to this work as a self-portrait expressing qualities of visibility and invisibility within the psychological and material realms and the struggles between the (un)seen. Fuenmayor replaces the Magrittian green apple with the green stalk of bananas, a tropical signifier that simultaneously connotes sexuality and Otherness. Nevertheless, Fuenmayor entertains a surrealist aesthetic that obscures the entire head region drawing comparisons between that which is seen and unseen.

Like the oversized champeta knife in Angulo Cortés’s portraits, Fuenmayor’s machete resonates with acts of labor being one of the chief tools used to cut banana plants in the field. However, in the four Los Encantos de la Violencia portraits from this series, the machete and banana are indicators of violence, weapons of choice, and markers of identity. The banana held in his left hand is connected to the banana-head arrangement. What therefore, are the consequences of consumption when eating the head of Mister Bananaman? Again, how are these gestures symbolic of the systematic erasure of banana laborers in the archive and yet, endemic to tropes of the hyper-sexualized Latino body as a consumable body? One of the ironies of these juxtapositions is that while Fuenmayor has placed bunches of bananas as the face of a man, the UFC placed a face (via the Chiquita Banana sticker) on their bananas. Nevertheless, as a consumable unit, the banana once devoured disappears into the body, losing its identity.21

Fuenmayor offers this parallel as a reminder of another disappearance: those slain in the masacre de las bananeras of 1928 is reflected in the dematerialized bodies in the work of Angulo Cortés and Fuenmayor. These developments are a call to the urgency of thinking about our past and present relationships between bananas and the body, memory and dislocations of memory, and banana futures.

The banana in this fashion becomes a political actor in the drama of food and rememory as a form of resistance. Rememory refers to the struggle of reconciliation and remembering of traumatic experiences that are often connected to a specific place or event. The disappearance of the consumable (banana) body and the erasure of the collective memory of the massacre become a singular disappeared entity. Rememory does not refer to a single individual’s remembrance, but rather it is the recollection of the collective. The body of the community as a whole constitutes the memory driven by the connective tissue of deep trauma, suffering, and fated forces. Both real and imagined reconstitutions of memory are bona fide answers to an amnesiac landscape. Rememory requires not only communal participation, but invention to fill in the gaps and interstices obliterated by institutions through brutality. Shedding light on these contingencies are the chandelier bananas in Fuenmayor’s Papare series (2013).

Fuenmayor traveled to the Papare banana plantation in Ciénaga where he installed chandeliers in the tops of banana plants. Chandeliers rose to prominence in Europe during the colonial period decorating lavish interiors. The larger and more ostentatious the chandelier was, the greater its value and status symbol of wealth, further emphasizing the affluence afforded by slave labor on colonial plantations. To emphasize this juxtaposition, Fuenmayor obtained various chandeliers on loan from luxury retailers. They were strung up in the canopies of the dense foliage and lit up at night powered by generators hauled into the rugged landscape. Suspended from the chandeliers were hands of bananas. The cascading form of the bananas dangled like the luxurious equivalency of the crystal chandeliers creating a double portrait of surrealist excess. Fuenmayor describes his approach thusly,

In the latest series, several Victorian chandeliers were attached to banana bunches in the midst of a banana plantation, lit at night and then photographed. The theatricality and dramatic nature of the imagery, subordinate the contradictory into a delicate and imaginative order, evoking a certain kind of reconciliation or tense harmony between two disjointed realities. As the past, the present, the exotic and the familiar collide, absurd and fantastic panoramas arise (Fuenmayor).

The disjointed realities discussed by Fuenmayor are aesthetically driven by the collision of two alien forms—a crystal chandelier normally lighting a prestigious interior and the exoticized/eroticized hands of bananas (figures 14 and 15). Fuenmayor’s experience in the Papare banana fields was accompanied by an almost 5 ½ minute video documenting the installation of the event. After obtaining permission from Papare, he was assisted by actual banana laborers who were compensated monetarily by Fuenmayor. In what becomes a performative pendant to the Papare series, the video is vital to the reconstructive fabric of rememory as an artistic practice.

A return to a banana plantation in Ciénaga is a return to collective trauma and yearning for wholeness through the theatricality of absurdity and hunger. This hunger for wholeness is closely tied to the landscape. Jason Young argues that, “even when we forget the meaning of those times and that place; even when we have never known, the very landscape retains the memory of it” (Stuckey, 395). He further illuminates that rememory “operates on the level of practice…as a ritual constituted by a ‘social landscape where resistant bodies, through time as dense as fog, imperfectly re-member, limb by limb that which has been imperfectly forgotten’” (395). Therefore, Fuenmayor’s chandelier banana installation can be understood as a ritualistic artistic practice of re-membering by resistant bodies healing that which has been forgotten. It becomes a convention of ghosts witnessing in the dark recollecting the members: both bodies and bananas.

Édouard Glissant encourages a return to the plantation matrix after that of the slave ship in order to “track our difficult and opaque sources” (73). This opaque past is both figuratively and literally illuminated by the chandelier’s luminescence in Fuenmayor’s work. The plantation matrices that produced incredible wealth also produced resistant bodies. So, although banana laborers of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries may not be referred to as enslaved labor, the policies of the banana republic replicate enslaved/forced/coerced labor practices. Rememory is an aesthetics of rupture and connection located in ecologies of consumption.22 The aesthetics of the chandeliers are not only illuminating vessels of opulence, but bodies of grief. The crystal chandeliers are complemented with clear crystal droplets referred to as “teardrops.” The teardrops shower the hands of bananas as they weep together re-membering the meaning of that place in Ciénaga where, on December 5, 1928, an unknown number of plantation workers lost their lives.

Conclusion