Only a few days have passed since the Suez Canal has been unblocked. Hundreds of ships waited for a week – from 23th to 29th March – because, due to an error in manoeuvring, the Ever Given container ship ran aground on the shore and blocked the passage. European countries were left on the edge of their seats. Their dependence on that narrow strip of sea – which is less than two hundred kilometres long – is substantial, not only in terms of goods but especially in terms of energy resources. Global maritime traffic has literally gone haywire, but Egyptian President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi doesn’t want to give up on the lucrative revenues that derive – or might do so – from a fully operational canal. Once again, Europe keeps questioning its dependence on energy and the logistic fragility that links its supplies to delicate international geopolitical balances – that goes far beyond the latest new story. The logistics of supplies is in fact ‘threatened’ by a myriad of factors.

The events relating to the Suez Canal have always affected Europe and the whole world. Or rather, they have always affected the dynamics of the capitalist economy.

Let’s briefly recreate the facts. The block was caused by the Ever Given, the container ship of 20,000 TEU (Twenty-Foot Equivalent Unit, the unit of measurement equivalent to a container), 400 metres long and weighing over 200,000 tonnes. At 4:30 am of 29th March Osama Rabie, chairman of the Suez Canal Authority (SCA), announced that the ship had been ‘set afloat again and made safe and 80% redirected in the right direction’. Since the afternoon of that same day, the container ship has been freed up, allowing the slow thinning of the queue of ships on hold: 429 in a few days, and we should consider that some ships of Maersk, MSC, CMA-CGM or Evergreen itself had already redirected the routes of their ships headed to Cape of Good Hope. After all, it seemed like the block had to continue. In the evening of 28th March the Egyptian President Al-Sisi himself had spoken, advancing the lightening of the Ever Given’s cargo – an operation that would have been extremely complicated – as the only way to get out of the deadlock and unblock the canal. Besides, in the morning of the 29th, Syria imposed a policy of fuel rationing, fearing that the block would have continued.

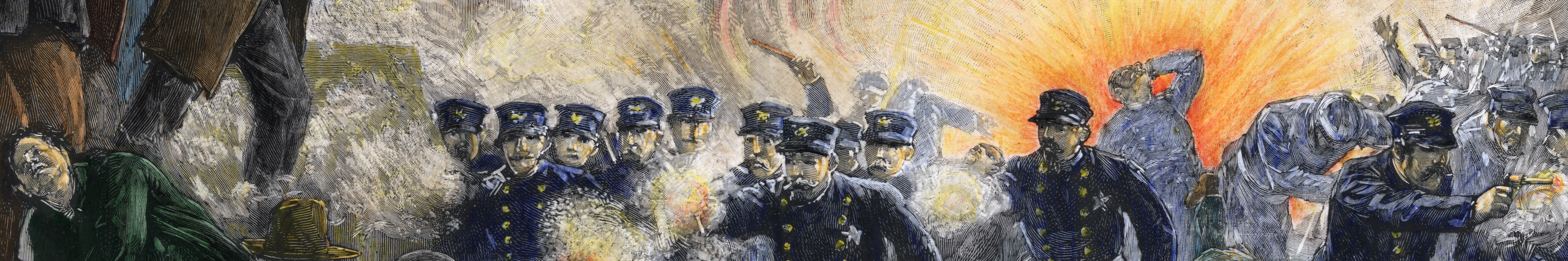

Since its inauguration in 1869, the Suez Canal has experienced a block situation several times. As a crucial passage for global value chains, the canal also inevitably represents a decisive ‘checkpoint’: when on 8th February 2011 approximately 6,000 workers staged a ‘wildcat’ strike in the cities of Suez, Port Said and Ismailia, losses were heavy.

In the Egyptian uprising process of 2011, the occupation and battles of Tahrir Square played a major role, but the fights in Port Said in the previous months and years – as well as those held during the revolution – were important premises for the fall of the regime of Ḥosnī Mubārak, who resigned two days after the strike. Going even further back, we can mention the action of counter logistics and nationalization of the canal in July 1956 by Gamal Abdel Nasser. This was a decisive push for the vote by the ‘Czech Six’ of the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom).

However, it is also useful to go back to the moment of the canal’s establishment, which is of decisive importance to affirm, in the second half of the Nineteenth Century, the British-led world market that would give rise to the so-called ‘first globalization’ – the surge of exchanges in global trade that occurred between 1875 and the First World War, whose levels would have been reached again only a century later with the beginning of the ‘Second Globalization’ in the 1970’s.

The construction of the Suez Canal finds its ideological matrix in the thought of Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon (1760 – 1825), a French philosopher who exalted industrial society, technology and science against the idleness of nobles, clergymen, soldiers and people of the court. He was an opponent of the Restoration and of the reflections of the Ancien Régime in it, he was a forerunner of a sort of socialist approach that directed the conflict not against the bourgeoisie but against the classes he considered to be parasitic, without whom the ability to produce wealth would have led to the end of exploitation. Therefore his politics became a sort of science of production and the industrial development was linked to the development of the communication routes. The paradigm of circulation – infrastructures and direct incentive between production and exchange – emerges as a new political concept.

In this vein, in 1833 the entrepreneur Prosper Enfantin, a follower of Saint-Simon, presented the first project for what was to become the Suez Canal to the Viceroy of Egypt, Mehmet Ali. In 1846, people associated with the Saint-Simonian movement set up the Société d’Études du Canal de Suez despite the Egyptian disinterest. Built between 1859 and 1869 by the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Maritime de Suez (Universal Company of the Maritime Canal of Suez), with a decisive contribution from France – 20,000 French shareholders own the work while 44% shares are held by the Egyptian Government – the canal immediately changed global trade, developed steam navigation (in 1860, only 5% of the ships was equipped with it) and increased European penetration into Africa, in addition to prompting the French to build the Panama Canal – unsuccessfully.

The intertwining of logistics and finance around the Canal has therefore been in place since the very beginning and, although there is no space here to discuss it, it should be noted that what happened in Suez can only be understood in the context of the simultaneous transformation undergone by the centre of French imperialism, Paris, – which made it the ‘Capital of the Nineteenth Century’ described by Walter Benjamin.

The works with which Prefect Haussmann built the modern metropolis (boulevards, stations, roadways, etc.) were in fact planned to make Paris a hub that could control the traffic flows moving from the Suez Canal to the European railways to the ports toward the Americas. After all, Marx at that time had already understood the emerging of these cruses, noting for example that ‘after the last general crisis of 1867, profound changes took place. With the colossal development of the means of communication – steam ocean liners, railways, electric telegraphs, the Suez Canal – the global market has become an operating reality. Alongside England, which previously held the industry’s monopoly, we can find a series of industrial countries competing with it; in all parts of the world, infinitely wider and more varied investment fields were offered to the capital that is in surplus in Europe, so that it could have been redistributed to a much greater extent, while local super-speculation could have been more easily overcome.’ Therefore the construction costs of the work were borne mainly by the French capital, though it must be kept in mind that the human cost fell entirely on the Egyptian workforce: 130,000 people died in the excavation of the work, which was essentially carried out by hand.

Claude Monet, La Gare Saint-Lazare

These historical elements seem important to us in order to highlight the longue durée useful to frame the present. The accident caused by the ship Ever Given – which occurred, moreover, at the same time as some major logistics strikes in Italy – reminds us of two things in particular. The first is the increasingly intimate intertwining of logistics and finance. Sergio Bologna spoke of this long ago: ‘container ships have changed from being industrial products to financial products’. The Ever Given is no exception. Owned by Taiwan-based Evergreen Corporation, it is part of a logistics fleet that goes far beyond just owning freighters. Actually, it goes far beyond just logistics. In fact, if we consider – more strictly related to transport – the 250 ships (with a total capacity of 1,300,000 TEU), over 100 passenger airplanes including Boeing and Airbus, various cargo airplanes, containers and warehouses (also totally automated like the one at the Taiwan airport), the Evergreen Group certainly doesn’t restrict itself to this. Well-known in the hosting business with luxury hotels and in the steel production with the Evergreen Steel Corporation, it also owns a pilot training centre and an aviation technology research centre (Evergreen Aviation Technology Corporation). Therefore, the Evergreen Group has what it takes to take on that ‘route to naval gigantism’ based – as Bologna writes – ‘on presenting a financial situation that allows large groups to obtain bank loans in order to buy new and technologically advanced ships’. This continuous race makes these companies appear stronger in the eyes of banks, but leads to overcapacity: a surplus of cargo space that in the long term inevitably leads to a fall of the interest rate (S. Bologna, ‘Tempesta perfetta sui mari’, Deriveapprodi, 2017). The failure of the South Korean company Hanjin in 2016 – which partially inspired Bologna’s book – is emblematic in this sense.

The container ship Ever Given itself is likewise symbolic in this race. The stranded ship is in fact one of the largest ships in circulation.

With a capacity of 20,124 TEU, it is a giant on the move with only a few ports to dock at – at least in Europe. But above all, it is a giant that often travels partially empty. As well as Bologna, many people are now questioning the ‘alleged economies of scale of naval gigantism’. Richard Meade, editor of the shipping and logistics specialized magazine ‘Lloyd’s List’, a few days ago published an editorial with a significant title: ‘Bigger ships create bigger problems’. Olaf Merk, administrator of ports and shipping at the OECD’s International Transport Forum (ITF), published a detailed report on ‘The Impact of Mega-Ships’ back in 2015. Merk asserted that, substantially, the trend to produce even larger ships – 21,000 or even 24,000 compared to a maximum of 16/17,000 only a few years ago – hasn’t gone hand in hand with the actual savings in transport costs. Quite the opposite is true: the need to expand ports and canals, as well as to increase the capacity of the docks and the infrastructure of the port hinterland, have almost cancelled out the economic benefits that the race for gigantism could have brought. Moreover, in the event of an accident, rescue operations would have become proportionally more complicated – as the Ever Given case proves. In the end, the block of the canal through which – according to Bloomberg – 12% of global goods pass and 30% of maritime containers, has raised the price of some materials, especially oil.

The second aspect that the Ever Given case reminds us of is how logistics is (geo)political. The route from the East through the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean Sea today is the shortest possible.

Departing from the port of Shanghai on 1st March, after stopovers in Ningbao, Taipei, Yantian and Tanjung Pelepas, the Ever Given reached Suez on 23th March and intended to call first at Rotterdam and then at Hamburg on 4th and 10th April, respectively. Shanghai-Rotterdam in 34 days (including numerous stopovers). About 9.5 billion goods per day pass through the narrow passage of the canal – a real ‘bottleneck’ in logistics jargon, around two hundred metres wide. A small river linking the economies of a few billion people, too fragile to represent the only East-West circulation axis. This is the background to two infrastructural, logistics and – after all – political colossal projects, which will be certainly revitalised by this accident. The first is the so-called Northern Sea Route, on which Russia is betting. Favoured by the melting of polar ice, the passage along the Siberian coast would reduce the journey between Tokyo and Rotterdam by about 40%, with a consequent reduction of the costs. Thanks to global warming and to the latest generation Russian icebreakers that will pave the way (if not for 20,000 TEU ships, at least for slightly smaller ones), the passage to the North-East will, on one hand, provide an alternative route for Europe-Far East traffic; on the other, it will give a considerable geopolitical power to Russia, which will remain in any case the fundamentally undisputed guardian of this route, since it borders with its coasts for the entire route or so. It is precisely around this issue that a political clash between Russia and United States is unfolding via Germany – which would be the main beneficiary of this new route.

The second project to be relaunched is obviously the one of China’s New Silk Road (the so-called Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI), a colossal infrastructure which – on its main route – connects Xian to London in more or less two weeks by train.

The BRI was very much wanted by Chinese President XíJìnpíng – as Simone Pieranni often reminds us – and basically has two main objectives. The first is to research for new markets that could absorb the manufacturing produced. The second is obviously geopolitical, linked on one hand to the image China wants to give to the world, and on the other to the creation of areas of influence through ‘the policy of logistical corridors’ – as Giorgio Grappi calls them. Directly embedded in the Chinese Communist Party’s constitution, the BRI gained importance already in the first phase of the Covid-19 pandemic, thanks to the aid that came from there, also in Italy. With this new, though brief, ‘Suez crisis’ it can only increase it.

In conclusion, we believe it is important to develop a political reflection that can interpret events such as the one reported by the mainstream media on the Ever Given in a light that is not contingent or merely ‘technical’. Therefore, we have tried to show both a genealogy of the Suez Canal in its logistic-financial entanglements and in its historical fractures, conflicts and struggles, and to place this event in the broader context of the global current events in which the logistic passageways are acquiring even greater political importance. It seems that these elements lead to the need to reformulate a political lexicon and its analysis, starting from the already full centrality – increased by the pandemic – of logistics and circulation as conflictual subjects of contemporary politics.

English translation for DINAMOpress by Gloria Bucari.