The purpose of this paper is to draw attention to an alternative cinematographic pathway, one that is often ignored but that was nourished through the struggles that broke out in Italy in 1968 and which became a form of underground opposition to the official structures of power. It thus demonstrates how film and cinema can sit in antithesis to the traditional circuits of power within a dominant culture.

Newsreels were able to reveal and represent the complexity of the revolutionary movements in the late 1960s in Italy. I will focus particularly on Cinegiornali Liberi (“Free Newsreels”) and Cinegiornali del Movimento Studentesco (“Newsreels of the Student Movement”), both of which sought to subvert the dominant cinematic model by fighting for access to the same communication devices used by that system. As a result, a new way of using media devices in a counter-informative fashion developed at that time. The terrain was actually one of counter-power, intended as antagonism and resistance carried out with the camera, which became a weapon against official power structures. Counter-power was the product of a struggle through which pictures came to defy the “surplus value”1 instrumentally given to them by the dominant power, at times making them an object of overestimation (associated with a precise ideological message that was functional to the same power) and at others one of undervaluation (when their disruptiveness became too dangerous).

Newsreels are a form of film in the vein of a reportage or journalism, structured in periodical news reviews, with a chronicler who conveys information on current affairs. The history of newsreels is often interwoven with political activity and governmental propaganda: it is often either the product of a state body, or under the strict surveillance of state authorities. However, in Italy in the late 1960s, Cesare Zavattini first and then the Italian student movement took the word “newsreel” and gave it new meaning, which opposed the term “counter-information” to that of “information” provided by the state apparatus. Use of the camera expressed a pressing need to disprove the “official” version of history, and for the people to become the makers and deliverers of news “lived, seen, suffered, enjoyed, analyzed in opposition to the state monopoly over information.”2

I will first discuss Zavattini’s involvement in directing the so-called “other cinema,” where the word “other” refers to the criticism aimed at the traditional cinematic apparatus. It is a practice that, beginning from the 1940s, ended up diverging from the canonical newsreel through the realization of the Cinegiornali Liberi, which became a pathway for active and direct participation in social processes. This experience really took shape in the early 1960s, and it involved a collective and self-produced cinematographic activity realized with light cameras. In essence, this was a form of action cinema that spoke to non-professionals, one disconnected from the logic of profit, an alternative opposed to the traditional systems of production and distribution. The goal was to surpass the industrial idea of film-making in order to remove cinema from the myth that conditioned its history, marking its destiny as a solely spectacular and commercial medium. This is why Zavattini used the definition of a “free newsreel,” intended as a film product that easily fit into the unfolding of social and political events and, as a non-standard free-form expression that remained far removed from the architecture and devices used in industrial production.

It also foretold what the routine style of the students’ newsreels would become. Based on the growing waves of turmoil in the late 1960s, the students heavily supported the idea of cinema as a political act subject to the revolution, which aimed to destroy the power dynamics within the system. Cinema was an outlet for the expression of militant groups that had the duty to take an active role in the revolutionary process. If the dominant class controlled the means of communication to spread their messages and ideology, the opposing forces needed to create an alternative circuit through which they could also reflect upon the experiences of the struggle, thereby conditioning or radically modifying the political scenario. This meant that the camera needed to be available to everyone, footage needed to be prepared as quickly as possible, and its legitimacy was a direct consequence of the key words of the extra-parliamentary Left. Cinema became a means of information distribution and political growth, an instrument through which to analyze class struggle, and a term of reference and identification for all the leftist militant groups.

Such a journey on the trail of “passionate cinema”3 should also reflect upon its stylistic form, which has oftentimes been negated, however, in the name of analysis from a historiographical perspective alone.

Zavattini’s Newsreels

The Continuous Search for the “Other Cinema”

In a 1969 text, in which he reflected upon his cinematographic career, Zavattini claimed the existence of a “process that has consequences only on thoughts and not on works.”4 With this statement, Zavattini did not just assume that retracing his artistic life exclusively through his subjects and films was impossible, but added the fact that he let himself be corrupted by professional collaboration with those involved in more traditional filmmaking, while he engaged in a different kind of cinema, an “other cinema,” where “other” expressed the will to escape submission to the laws of the “film system,” which was directed especially at commercial targets. As such, Zavattini was making a conscious distinction between “official” cinema and an “alternative” one. This dichotomy was probably the primary engine of Zavattini’s considerations towards “other cinema”5: the work made inside canonical filmmaking entails the basis to question and challenge it.

The problem in studying Zavattini is largely due to the incompleteness of his works, the unresolved knots and theoretical drafts that results in a gap, a disparity between ideal tension and practical results. Though faced with his massive corpus of works, bulk of notes, speeches, ideas, thoughts, and controversies spread across diary fragments and project drafts, it is still possible to reveal the persistent core of his research and experimentation. Even considering the irregularity of his artistic and political elaboration, what remains stable across the corpus is his search for a new cinema.

Il Cinegiornale della Pace (The “Peace Newsreel”)

In an October 1962 issue of Rinascita magazine, Zavattini publicly announced his idea of a Cinegiornale della Pace (1963; “Peace Newsreel”). Forefather of the Cinegiornali Liberi, this newsreel was a monographic installation that, while still investigative in form, presented the underlying topic of peace. To pursue this theme, a commission was put in charge of choosing “video clips…suggestions…advice…submissions”6 among those sent in by the public. This model of report-journalism reflected a constant inquiry, complaint, and urgent interest in the processes that governed daily social life. Zavattini, well aware of the “deadly shadow of world-scale nuclear conflict,”7 intended to “create a conscience and a culture of peace.”8 Therefore, the aim of Cinegiornale della Pace was not only the audio-visual product itself but also ethical and political growth, both for those who partook in its production and for the audience. The idea was that peace could only be achieved through a new culture, a new awareness, made possible by collective mobilization, which would annihilate the old, elitist culture.

Such a renewal can be analyzed through Antonio Gramsci’s concept of cultural development, which is the precondition for the democratic growth of a country. This new culture allows for the crossing of the boundaries of conventional cinema. It thrives from collective contribution, pluralist approaches rooted in tangible reality, and from mass involvement in film production, which leads to a questioning and redefinition of traditional cinematographic work. Calls for collaboration were now addressed to anyone who “owns a camera,”9 thereby equating filmmakers with artists and anyone with a passion for cinema.

What stands out here as the main difference from the later experience of the Cinegiornali Liberi is the presence of an editorial board in charge of selecting and putting the material together. The board was therefore in a superior position, making it no longer possible to truly express freedom of speech on a given topic, as Zavattini had suggested. This centralized control of the information and undermined the intention for horizontal and collective construction that was intended to act as a cornerstone for the whole project. The result was the first and only issue of Cinegiornale della Pace, screened in 35mm and 16mm film in May 1963 during a morning projection at the Supercinema in Rome. Produced by Zavattini alongside other young filmmakers, its various episodes still fit perfectly into traditional dynamics. The “Peace Newsreels” were a final attempt by the famous screenwriter to conjugate his utopian concept of a “new cinema,” with its revolutionary undertones, into an industrial-grade production. The reason for the failure of this experience can be found in the absence of new historical conditions necessary for its reception along with the lack of radicalization of the larger political struggle. Nevertheless, the Cinegiornale della Pace, even in this early phase, bore the idea of the “Free Newsreels.”

I Cinegiornali Liberi (The “Free Newsreels”)

By analyzing the course of his cinematographic production beginning from the early 1960s, it is easy to see how Zavattini prudently began his career on the sidelines of the world of cinema and then left that world when he saw that the time was right. In this instance, we see how his position became increasingly radical when it came to the main topics of film production, such as the importance of collectivization, which re-emerged as a contested topic during the explosive revolts of 1968. In Contro il passato nel cinema (“Against the Past in Cinema”), written in 1965 for the occasion of the panel discussion on Posizione e funzione della cultura italiana negli anni della Resistenza (“Position and Function of Italian Culture in the Years of the Resistance”), we see an enumeration of the opportunities missed by Italian cinema and, at the same time, a presentation of future projects, which ended up representing the baseline of the Cinegiornali Liberi proposal. Zavattini himself, while reviewing many great names of Italian cinema, believed that cinema was, up until that moment, essentially a “bourgeois phenomenon”10 incapable of having “a decisive influence on the vital processes of society, whereby it is capable of changing both individual and collective structures.”11 It was a cinema, therefore, “betrayed by those who produce it but [that] still has the possibility of redemption in this radically new domain.”12 Thus, by decanting the characteristics of the “new cinema,” Zavattini spoke of “cooperatives [that] become centers that go beyond the film itself and place themselves in the starting position of cinema.”13 It was precisely these collectives, made up of “men before films,”14 that would become the nucleus behind the idea of the Cinegiornali Liberi. Once again, he was appealing to the contribution of non-professionals, amateurs, and “new talents recruited across fields.”15 In this way, again, the actual product was subordinated to the process through which it was created, a process of ripening that materialized in a constant “analysis, documentation and guerrilla warfare”16 locally. In this context, “constant” meant a continuous becoming of daily life, which no longer responded to traditional timelines and the interests of the industry, but which sought to become irregular and boundless. This related to a broader reflection Zavattini made on the cinematographic medium itself. He hoped for a return to the original potential of the medium, to its endless possibilities, since cinema was nothing but a means of “minimizing mediations and obligating us to make contact”17 with the real, with methods of analysis and current choices. The first launch of the newsreels appeared on the pages of Rinascita in August 1967. Zavattini believed that “groups of non-cinema” would be able to “enter people’s homes” and kindle “guerrilla wars” for many through a type of cinema that would portray “the needs…of the world.”18 Once again, the hope was for cinema to act as a medium of counter-information, for cinema to become an outlet for active and direct public participation. From this point of view, Cinegiornali Liberi justified its distinct opposition to traditional formats for information distribution, which were used by Cinegiornali Luce and Incom. What Zavattini focused on was not the word “Cinegiornali” (newsreel) but primarily the adjective “liberi” (free):

Freedom is not a generic, abstract, and rhetorical invention: it coincides with the intuition of the medium of cinema. We all agree that the press should be free, that theater should be free, but especially that cinema is either free or destined to fail.19

The focus of newsreels was therefore to use the camera as a tool for emancipation from the traditional language that Hollywood (among other film industries) created and institutionalized. No rules were set, not even regarding aesthetics: cinema was to remain free and shun prejudice. The length was not important and the topic could vary, so long as it felt an “urgency to go public.”20 Anyone who wished to participate could contribute with ideas or money, even if they had no technical knowledge. By allowing everyone to participate, the industry was freed from the technical qualms that had been mythologized to keep it within narrow bounds. The results were collective forms of cinema where teamwork was the cornerstone that went against the individualistic, dominant form of filmmaking. In this respect, there was also a search for new distribution circuits that were “outside of and in opposition to the traditional channels.”21 Suggestions for new distributive pathways were met with Zavattini’s encouragement that “All you need to project a free newsreel is a wall,”22 meaning that it was through public displays (not through traditional cinemas) that mass involvement was possible. Newsreels were to overthrow the traditional role of the audience, who now felt as part of the enterprise and no longer a passive consumer subject to “an inferiority complex when faced with a film camera,” but who instead became an accomplice and “co-author.”23 Meanwhile, the increased availability of lightweight cinematographic equipment was the precondition for new forms of newsreels. Film-cameras were becoming weapons, “tools with which to analyze and intervene.”24 Specifically, the “8mm camera is becoming the symbol of Free Newsreels’ fight against the country’s current regressive and repressive situation.”25 In this phase, Zavattini was searching for accomplices among intellectuals and people in the cinematic industry. Fabio Carpi, Ugo Pirro, Mino Argentieri, Giambattista Cavallaro, Giacomo Gambetti, and Gianni Toti are the names that would appear in the first edition of Bollettino in June 1968.

Meanwhile, as protests broke out at universities across Rome, Zavattini continued with his work while mainstream media voluntarily ignored the uprisings. Even “Free Newsreels,” whose objective was to not “arrive late to the crime scene”26 and whose members considered it to be “immediate cinema,” managed to miss key stages of the 1968 protests. It is for this reason that the next step was to move the whole cinematographic production from Reggio Emilia (where it had been born) to Rome, which became the headquarters of the Newsreel’s Centro Nazionale (National Center).

The spring of 1968 marked the birth of the first editorial board that created the first number of the “Free Newsreels,” which was realized as a debate held inside Zavattini’s home, during which the meaning and political function of newsreels was the central focus. A certain degree of ambiguity can be noticed between, on the one hand, the declared urgency for a new type of cinema that took to the streets to interpret social movements and contradictions and, on the other, groups of intellectuals perched inside their own houses, discussing among themselves. For this reason, Cinegiornale n.1 (1968; “Newsreel n. 1”) felt claustrophobic, made worse by the use of an insistent sequence plan that sought to support the flow of the discussion.

Another advancement for newsreels at this time was the contribution by the discussants of the mentioned debate in an edition titled Cinegiornale di Roma n. 01 (1968; “Newsreel of Rome n. 1”). This newsreel was the result of a joint effort of the first editorial board, with different formats and styles that ignored the limitations of film production. The material used was taken from pages of newspapers, photos, signs, and a number of other places. The characteristic features were the focus on symbols of power, the irony and sarcasm spread throughout the film, and the emphasis on the need for free information. In this sense, the function was clearly aimed at a more allegorical and narrative montage with an expressive use of sound, as demonstrated by the sound of shelling layered over images of St. Peter’s dome, or the laughter during the dismantling of an electoral stage, or the phrase repeated by Pope Paul VI (pace fratelli, “peace brothers”) while images of massacres and disasters followed. This seemed to anticipate the production of the Cinegiornale libero di Roma n. xyz (1968; “Free Newsreel of Rome n. xyz”) where Elio Petri, accompanied by Pirro, interviewed Daniel Cohn-Bendit, the leader of the ongoing French protests, with a backdrop of St. Peter’s Basilica.

In the meantime, a collective in Turin produced the first and only issue entitled Cinegiornale Libero di Torino n. 1 – Scioperi unitari alla Fiat (1968; “Free Newsreel of Turin n. 1 – United Strikes at Fiat”). The film showed the strike called against Fiat’s policy on working hours and rates, which began on the 3rd of March 1968. The camera moves swiftly among the protesters while a voice-over lists data on the intensification of worker exploitation. The production was shot with an invertible film that allowed for copies to be developed quickly, while assembly cuts were made directly on the original version and sound created by drafting a magnetic track. This embodied the need for “immediate cinema” to become part of the struggle and a tool for strikers.

The political and cultural tensions that had been growing also found their natural outlet in the protest against the 29th International Film Festival in Venice. Newsreels appeared on the scene with their first hands-on production, and it was precisely on this occasion that the first encounter and clash between the various Italian cinematographic forces of those years took place.

Beginning on August 24th, the protest against the statutes of the Venice Film Festival, which dated back to the Fascist era, began, together with the Coordinating Committee for the boycott. This episode marked the highest moment of film activism in Italy in 1968. In the weeks following the Venice protest, the movement passed through a period of reflection followed by a phase of profound transformation. At this time, some authors of Italian cinema decided to give up strictly cinema-related activities and dedicate themselves to militancy and full-time political activism. Others chose to further investigate the relationship between political commitment and moving images, putting themselves completely at the service of student and worker mobilizations. It is from this point onwards that we may begin referring to groups of the extra-parliamentary Left, developed partly from the ideological development of previous realities, and born partly after the 1968 revolts. These extra-parliamentary groups fought with the traditional Left for hegemony in those areas considered in need of political intervention. They considered factories as the most prominent of these arenas of intervention, and they considered the working classes as a new collective actor. Similarly, Cinegiornali Liberi moved closer to the realities of factory workers. Beginning from this moment, Zavattini established a close link between cinema and politics and between cinema and history. Cinema was to be “a tool for mobilization that has the aim of awakening people’s conscience against the current situation of regression and repression.”27

In the first days of November, another collective formed with the objective of creating the Cinegiornale Libero n. 2 – Apollon. Una fabbrica occupata (1969; “Free Newsreel n. 2 – Apollon: An Occupied Factory”). The work tried its best to reconstruct the struggle of the workers of Apollon typography to defend workers’ rights, which had begun in 1967. The film was the first ever representation of the occupation of a factory, and it was shown for the first time in the factory itself in February 1969. It attracted quite a large following and experienced considerable “success.” It immediately gained the approval of all the traditional Leftist forces: the PCI subsidized part of the production through Unitelefilm, which was linked to the party and which helped with the circulation of the material.

The Cinegiornali Liberi movement thus saw the birth of an alternative form of distribution and the confirmation of the working class as the protagonist of a new era of cinema. However, newsreels now stood in a position of ambiguity: on the one hand, the Communist Party supported them; on the other hand, they declared themselves independent from traditional power structures and separate from the old tradition of filmmaking. It is precisely for this reason that the film provoked very different reactions: whereas the parliamentary Left supported it, the extra-parliamentary Left, including student movements and various groups of militant cinema personalities, opposed it. This last group accused newsreels of not managing to break from the past and from traditional power structures. In essence, the Apollon, accused of serving as propaganda in favor of the PCI, was criticized for not being militant enough. Furthermore, the film, which was co-produced by Ugo Gregoretti, did not tell the true events as required by “traditional” militant cinema, but offered a fictional reconstruction with the workers themselves as protagonists, structured and then dramatized. One might say that the narrative character of the work constituted the film’s greatest element of success. In any case, Apollon’s merit was ultimately the component always postulated in any militant theory of cinema: the coincidence between the production and reality and its ability to appear internal to social processes. After the film was shown in Italian factories for several months, crowdfunding increased so much that the Apollon factory was able to reopen.

From 1969 onwards the second series of Cinegiornali Liberi began, which was more stylistically mature than the previous editions and “characterized by a more ‘authorial’ feel.”28 This was the case for Cinegiornale Libero n. 5 – Battipaglia (1969; “Free Newsreel n. 5 – Battipaglia”), in which an off-screen commentary explained the causes of the national crisis, which led to the strikes against the closure of factories in April 1969. What followed was a series of shots of police cars in flames and a testimony from the sister of Carmine Citro, killed during a demonstration. The showing of this production was itself filmed and featured in the newsreel Battipaglia: autoanalisi di una rivolta (1970; “Battipaglia: A Revolt’s Self-Examination”). In this edition, we find inserts of the investigation and close-ups of the spectators gathered at the Chamber of Labor. The debate that followed constituted a summary of the events and issues that afflicted the country, but in the aftermath nothing changed. The opening scene of the newsreel Sicilia: terremoto anno uno (1970; “Sicily: Earthquake Year One”) is a helicopter flying over the remains of the Belice Valley. This is followed by photos of men reaching to the sky, waiting for aid that will never come. A camera car shows the destroyed streets of Sicily, while a song in dialect accompanies the images of the dire condition of the survivors. Notable is the use of sound in the last part, which shows muted images of writing on walls and protest signs that alternate with the sound of police sirens on a black screen, as if to show that the only answer to the struggle that authorities were able to give was the use of force.

The title of the Cinegiornale Vajont: 2000 condanne (1970; “Vajont Cinejournal: 2,000 Condemnations”) refers to the number of deaths resulting from the Vajont disaster of 1963, which led to the disappearance of the village of Longarone. The work used archival footage to identify the causes and responsibilities of those behind the massacre.

Il Cinegiornale Libero del Proletariato (The “Free Proletarian Newsreel”)

The premises of this new endeavor were collected in the Apollon story: through it, contacts and relationships with the traditional forces representing the labor movement were anticipated. The Cinegiornale Libero del Proletariato (“Free Proletarian Newsreel”) was put forward as “a cinematographic tool of information at the service of labor movements”29 and “the cinematographic expression of the mass organizations, from unions to cooperatives, to the ARCI, a means for them to promptly and objectively report all of their problems to the public.”30

Although the occupation of the Apollon had brought to light the need for (counter-)information, it later became clear that strict dependence on political parties and unions proved to be inevitable for the mediation between institutions and protest movements. Even then, it was not clear who was to bear the realization of such productions and what the nature of the relationship between the Newsreel’s Center and the “mass organizations” was to be. These are among the questions that remained unanswered because none of Newsreel’s members were willing to produce new material in this direction.

As noted, Zavattini relied on structures close to the PCI to carry out his Cinegiornale Libero project since the very beginning. If before 1968 this was due to the need for practical aid for his productions, however, after the turmoil of 1968-1969 this was no longer the case. Zavattini was not adequately prepared for the profound changes taking place within Italian society, the world of labor, and its image, so he continued collaborating with the Party and with union structures of the parliamentary Left, just when such traditional bodies lost the ability to exercise power over the working class. This experience, therefore, which ended in 1970, did not produce the desired results. A strong disparity remained between the initial project and the results achieved. In fact, thinking back to the newsreel operation in its entirety, we notice that the productive initiative was taken on almost exclusively by professional filmmakers.

Zavattini’s work can thus be seen as the first attempt, “at least on a theoretical level, to subvert the ‘capitalist division’ of labour: his is a proposal for the mass appropriation of tools for culture and communication.”31 This approach, however, was but the pinnacle of a newfound form of humanism, sometimes portrayed as generic reformism (always formulated to appeal to an ordinary audience), distinctly separated from the growing politicization of social struggles. This is precisely what caused the end of Zavattini-like newsreels, whose legacy was partly collected in the newsreels of the Roman student movement. At a later date, this group would seek to create a direct link with the struggles of 1968.

I Cinegiornali del Movimento Studentesco (The “Student Movement Newsreels”)

Newsreels 1 and 2

The first necessity imposed upon those who wished to follow in the tracks of a new cinema that was so often negated was to find a principle of order, which allowed them to move across a subject that was so dispersive yet rich in implications and self-reminders. In this sense, the starting point for this discourse was an interview of Zavattini by Mino Argenteri, which soon became the central point of balance for the “Free Newsreels” experience. Zavattini would confess that:

There was a moment where all of this was working. Well, at a certain point of the discussion there were some youngsters, and someone who had a really bad influence among them. I can still see him: he hugs me, like, but he had a negative influence. He was a person full of wit, but oftentimes he crossed over to an empty negativity. Suddenly he said, among all of us: “What are we doing here? You know that we can’t change the State. It must be destroyed. We can’t work with the State.” “Sorry, I have to object, if you came for this, let’s go out and throw rocks, whatever you want, but what do your ramblings have to do with the free newsreels?” It was the end; there was no more possibility to debate and that episode was crucial because, after all, no one was 100% ready. Everybody was 99% ready and all it took to undermine everything was such a person.32

We can consider this statement as a temporal divide, in a phase where we can see how two complementary dynamics intersected on the theoretical plane but were far apart at the same time. On the one hand, we have the “Free Newsreels” that were approaching a painful and final end, and on the other the achievement of full maturity for the experience of the “Student Movement Newsreel,” which was the result of a new political consciousness born in the season of revolts in 1968. The matrix of its birth and the political category through which we can evaluate it are to be sought in this historical frame alone.

The 1968 protests were responsible for the reversal of an entire conception of life, and they brought new subjects onto the scene. At center-stage, there was radical disobedience, a cultural revolt against the national fathers, against authority, against all the mental structures, habits, and sexual customs of previous generations. In such a climate, cinema supported and amplified revolutionary passions, revealing conflicts as fluid where history and the present combined and were located in the midst of events. This form of cinema imposed critical reflection and action, and it despised the cinema of happy endings and catharsis.

This was a rebirth that flooded all of Europe and more, with the objective of reporting, documenting, problematizing, and taking action to address what was happening, trying to untangle the traditional cinema distribution knot and create a different audience. It was the notion of “communication,” meant as the circulation of information that came from above and which was destined for those below, that was to be removed.

Therefore, the common theme, the ordering principle, was found in the questioning of political and economic foundations and cultural tendencies, alongside the need to change the structures of production and to deconstruct the language and social relationships inherent in cinematographic dynamics. By doing so, cinema renounced its historical role as a bringer of a dominant ideology and instead came to favor the political struggle. The term “militant” was not another adjective that needed to be applied to the word “cinema,” but it exhibited its substance: cinema as an expression of the organization and fight against the system, an artistic practice that reached out to the revolutionary movement. This was a new form of cinema whose characteristics were those “of having been shot on a very small budget, in the margins of the commercial production system and of having the goal of short-term political intervention or long-term ideological intervention,”33 all in the middle of the events, without aspirations of length or completeness, “as a cinematographic leaflet” that “makes the subject of the political action owners of the information.”34

In this context, (counter-)information replaced the concept of (self-)expression, which was linked to a bourgeois and individualistic point of view. Cinema was instead to be of service to counter-inform the “masses of spectators…and notify them of [the] tricks of communication.”35 Moreover, through close-up knowledge on how to use cinematographic equipment and through its autonomous usage in various situations, those who struggled could finally portray their own experience, thus giving new life and vivid expression to political action.

Newsreels of the student movement took this path to bring counter-information to students. This cinema was therefore an “expression of collectives of militants that place themselves outside the system and actively intervene in the revolutionary process.”36 They attempted to put into practice an alternative to communication and mass information, derived precisely from a misrepresentation of what was happening during the student protests on behalf of traditional media outlets and information channels. The objective was to maintain the immediacy of such information and its use both inside and outside of the movement: inside to check on the movement’s own progress; outside to prove that the protests were not only carried out by a few hundred, as the media had been saying until then. If the capitalists control media to share their own ideology, there is a clear need for an alternative circuit through which to speak about and reflect upon the struggle and offer a revolutionary perspective. At the same time, a repertoire of images and filmic behaviors must be created, which constitute a reference point and identification term for all subversive forces.

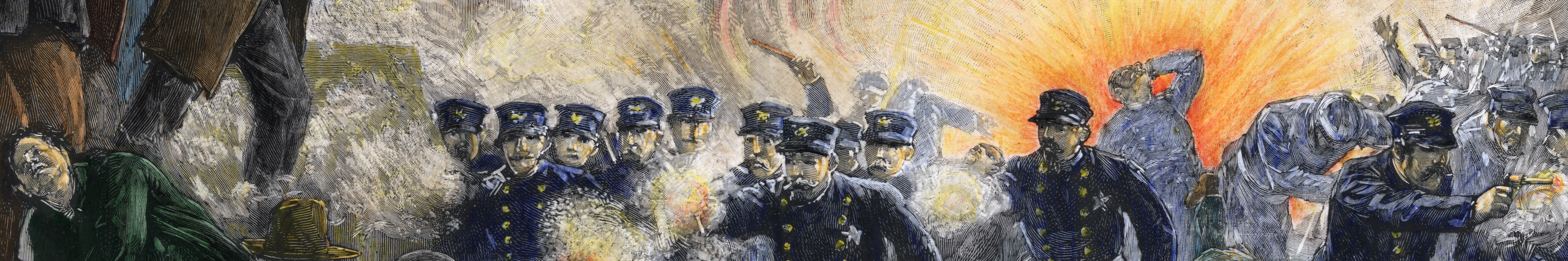

The actual birth of the newsreels can be narrowed down to Autumn 1967, when a filmmaker suggested that the actions of the Movimento Studentesco (Student Movement) be filmed, during an assembly held in the occupied Faculty of Literature and Philosophy of the University of Rome. A few days later, during an assembly, the decisional board for the student movement made the official proposition, and it was swiftly approved. From this moment on, the militants in the Movimento Studentesco were directly in charge of the film camera in the streets and at the protests, and they used it as a tool of resistance. Thus, at the beginning of 1968, Cinegiornale del Movimento Studentesco n. 1 (1968; “Newsreel of the Student Movement n. 1”) was born. A sacred choral sound was juxtaposed with the images of the clashes of Valle Giulia. The construction of the sound, mixed perfectly with the sound of police sirens and protestors screaming, seems to introduce a certain degree of irony, which reduced the pompousness present in some of the images. This was inherent to the function of the newsreel: to follow and document the struggle in order to inspire reflection and awareness. The film began with a declaration of intent:

Newsreels are an open initiative to anybody belonging to the Movimento Studentesco. Anyone who wishes to collaborate can sign up for whichever part of the board for the production of the newsreel they wish at any moment.37

All students with cinema-related aspirations responded to this invitation and were given different technical and organizational tasks. The project had a horizontal production line: at the beginning, an expert shared their expertise with the militant students and taught them technical knowledge; later, the students used the knowledge and available equipment to make the expertise widespread among the militants. Cinema became a tool, a “mouthpiece for the profound requests of the masses (respect for power; respect from politicians).”38

The topics of the first newsreel were: the sit-in of students from the Sapienza University; the assemblies held with the participation of political militants; the procession at Piazza Cavour; the protest in front of the rectorate; and the arrival of fascist forces in front of the occupied Faculty of Literature. It was first shown in the university’s Great Hall and provoked great enthusiasm and support among the students. The financial support was possible thanks to a series of collections during the showings and through donations from the Board of Directors and from intellectuals such as Alberto Moravia and Vanessa Redgrave.

The topics of the Cinegiornale del Movimento Studentesco n. 2 (1968; “Newsreel of the Student Movement n. 2”) included: the occupation of the university; the assemblies in the university classrooms and the writings on the walls of the corridors; the night-time demonstrations in Piazza Esedra; the demonstration at Piazza Navona; and that in front of the Rinascente department store in Piazza Fiume. The shots are juxtaposed with archival material, particularly with photos of the events and cuttings from newspapers of the time.

Interesting is the quotation from a movie that shows the fighting style and clashes of Japanese students in 1968, in an attempt to extend the topic beyond national borders. The (rhetorical) voice-over of traditional newsreels was replaced with captions, which were set at moments of struggle and during the speeches of militants, whose voices are the background sound for images of demonstrations and assemblies. Some shots from above are followed by close-ups of the masses of protestors, where a 10mm wide-angle lens was used to facilitate clear shots from afar, while close-up shots “require being on the front line, literally close to the events.”39 The rhythm of the montage is fast, with sequences no longer than 45 seconds, which undermine all chances for continuity, which was typical of traditional cinema. It seems that we can speak, at least for the first two newsreels, of a type of montage that tended to fragment shots rather than tie them together, evaluating individual images as meaningful blocks in and of themselves, rather than as links to each other. It is with this style of montage that one understands the criticisms often made of newsreels as being exclusively an “enthusiastic recording of what is new” without any “awareness of the political dimensions of the movement in progress.”40 Such awareness is replaced by “wonder at what is happening, contemplation of events in an enthusiastic and celebratory sense.”41 This realism, which was representative of many images yet to come, was striking, it changed what had been considered traditional TV and became the classical imagery of the time. Among these is the sequence shot on the stairs of the Faculty of Law when militants associated with the neo-fascist group Movimento Sociale Italiano (Italian Social Movement) launched a bench from the second floor, an action shown several times through a “conceptual” editing style to reinforce the signifier. Another element that needs to be highlighted is the so-called “self-analyzing component,” a reflection on the language of mass media found specifically in a scene in “Newsreel n. 2,” where an image of the student movement protest is shown through a television screen. The desire was to reflect and denounce the ideological falsification of the traditional language of media.

Newsreels 3 and 4

“The state is not to be reformed, it is to be destroyed”: this was not only the slogan that ran through the assemblies and demonstrations, but also the general spirit of the cultural movements in Italy in the late 1960s. It was the emerging voice of a restless generation that wanted “everything and now,” that rejected authority and dogma. It was a river waiting to overflow, a spontaneous fire, which was breaking the rules of interpretation.

In June 1968, protests erupted at the International Exhibition of New Cinema in Pesaro. The student movement accused the festival of “being a pseudo-alternative to capitalistic impositions, a reformist initiative.”42 Pesaro was at the center of attention because the exhibition was an integral part of its redesign as a sign of a new democratic system, accepted by the traditional Left. For the protest, representatives of the Movimento Studentesco and of the magazine Ombre Rosse composed a text together, which was configured as a response to the festival and its cultural and political motives. Effectively, the document went beyond the contingent situation of the contestation of the festival and ended up constituting a pragmatic political and cultural platform for all movements and groups on the extra-parliamentary Left.

The starting point of this document was the coupling of cinema and politics, which was followed by a dialectical interpretation of two fields that were so distant and yet which belonged to the same superstructure of “politics” and “ideology,” the role of “significant practices” among which there was of course cinema, intended as an “ideological apparatus of the state.”43 Bourgeois ideology was fed by ideological apparatuses and thought of as a cornerstone of class struggle. Therefore, class struggle in the superstructure had as its main ideological manifestation a resistance against all forms of bourgeois intellectualism. However, the highlight was the conviction of a dominant ideology that acted in disguise: it could take different forms, such as (and particularly), in the field of political-cinema binomial, that of “Progressivism” through the so-called “fringes of ideological coverage.”44 These fringes attempted to offer false alternatives “that can contribute to the modernization of the system”45 and to guarantee intellectuals the necessary platforms that gave them the illusion of “pseudo-autonomy.”46 In this way, the system divided labor, which is a natural and fundamental need for capitalistic societies. Capital directs and controls possible outlets of contestation: the wish to change the world is subsumed and transformed into “an updating-modifying action of expressive structures”47 that already exist. For this reason, the student movement manifested its full force against the festival in Pesaro that perfectly represented the system described thus far.

The direct consequence of this topic regarded the impossibility of culture to be revolutionary within a bourgeois context. In a bourgeois society, even the culture that aims to oppose and desecrate the system remains bourgeois. Even the request of certain intellectuals seeking a freedom of culture in “a slave-like society like the bourgeois one”48 is clearly a chimera. The struggle aims not so much at freedom from intellectuals, a “separate and privileged category,”49 but at the liberation of all of society. Only in a socialist society, whose objective is the abolition of the division of labor, is it meaningful to speak of freedom of culture. For this exact reason, the exhibition in Pesaro conveyed the process of “art as specialization,”50 where ideological stances could be neutralized and all uncomfortable meanings could be removed from forms of artistic expression. Specifically, the cinematographic criticism of which Pesaro was an expression endorsed reactionary and potentially subversive films and rendered them harmless with “a purely linguistic analysis.”51 To oppose this, the Movimento Studentesco suggested “three hypotheses of theoretical work”52: 1) “a non-objective function” of art, which included the unveiling of the mystification of the neutrality of culture; 2) “the rejection of the ideology of the specialization-competence of intellectuals”; and 3) “the needs for political judgment…to verify, clarify, and motivate the hypotheses of cultural work.”53

What becomes clear in the second part of the document is the focus on a new cinema intended as a “political act” at the service of revolutionary forces, meaning a practice of the “demystification of power relations in a system” and an orientation towards “the clear will to destroy such a system and a close analysis of class struggle.”54 Cinema was to remain outside the system and be a mouthpiece for those who rejected traditional intellectualism and its role as a moral and political guide. Intellectuals wishing to participate in revolutionary causes were expected to annul their positions as intellectuals and become one with the working movement, with farmers, and with students, if they were to become true militants.

The result was a didactic film that aimed to explain political events, “showing the truth behind class struggle,” taking on the function of “comparing, discussing, and elaborating the process that is awareness”55 and using it as a tool for stimulus, information, and political growth. It was a kind of film to be projected in all the places where struggle occurred and where revolutionary forces united, using every channel available, including occupied faculties and schools, workers’ clubs, and culture centers. This is how a collective and horizontal work process was finally actualized, by focusing on the context of production, distribution, and its uses by the masses. What distinguished the newsreels was precisely a collective management internal to the student movement that set it apart and placed it in opposition to the dominant culture all while using its own traditional circuits. It was an anti-narrative and anti-commercial cinema, a cinema directly involved in reality and “opposed…to every authorial (therefore authoritarian) form, and linked to individual subjectivity.”56

One horizon and reference point for cinematographic practices that refused the director-author ideology favoring cinema as a “means of knowledge, of communication”57 came from Latin America, specifically from the Cine Liberaciòn (Liberation Film) collective. Central figures of this so-called “third cinema”58 were Ferdinando Solanas and Octavio Getino, from whom the work-manifesto La hora de los hornos (“The Hour of the Ovens,” 1966-1968) was presented as a global preview at the fourth year of the Pesaro festival. The film-essay drew the attention of militants from the Movimento Studentesco due to its strong ideological and political layout, which they found “useful” for the “process of liberation.”59 The analysis of oppression and its various forms became the premise for direct action in the struggles of the masses, an occasion to experiment with new language and rediscover cinematic means and their ability to capture reality and its contradictions, through which truly creative work became possible. Clearly, in this context the only appropriate slogan, which was printed in capital letters on many posters, was “CINEMA’S TASK SERVING THE REVOLUTION IS TO HELP CHANGE THE WORLD.”60

With the arrival of spring, the Cinegiornale del Movimento Studentesco n. 3 (1968; “Newsreel of the Student Movement n. 3”) and n. 4 (1968; “Newsreel of the Student Movement n. 4”) were finished. Both reflected the ripening process of the Movimento Studentesco, which went from being disorganized, confused, and self-obsessed to “attempting to synthesize and research new perspectives.”61 The last two newsreels are witnesses to the tension that revealed the attempt to conquer new political fields, such as the working class and the outskirts of big cities. This shows the internal management that lay parallel to the student movement in Rome. It is by no chance that in newsreels 3 and 4 we see scenes shot in construction sites and courtyards of social housing groups, places identified as a terrain for political action and intervention. It was “Newsreel n. 3” that introduced the Working Class Council to the scene, at the construction site of Casal Palocco, but also at the demonstration in Parioli (Rome) against the Regime of the Colonels, the national demonstration against police brutality in Pisa with the Movimento Studentesco, and finally the demonstration and violence in Piazza Cavour. In the fourth edition the Piazza San Giovanni demonstration for the liberation of Antonio Russo was documented, together with the night-time violence in Campo De’ Fiori between students, workers, and policemen. “Newsreel n. 4” ends with images of a “potential past” that look a lot like the first violent outbreaks in Valle Giulia. The film camera is, sometimes, fixed with faces going past it or towards it, and sometimes it follows events closely by capturing images full of people fighting together. It may be exactly this complexity, these real aggressions, that truly show the essence of a historical period full of utopias, shock forces, dissent, rebellion, creativity, and spontaneity.

During the collective scenes, the directors oftentimes zoom in closely to capture gestures, a sign of struggle, or a note of coercive behavior against militants. Close-ups on faces are limited and are mostly entrusted to the “defenders of the established order,” as shown by the close-up of a Vietnamese soldier wearing a gas mask. Both newsreels make extensive use of archival materials from all over the world. This hints at the idea that all anti-imperialist movements found their political value within a common revolutionary strategy against capitalist power and bourgeois state structures. The captions of the first two newsreels are substituted with large snippets of speeches by political leaders. The constant presence of spoken text throughout actually makes the final product flow less smoothly and creates greater difficulty in understanding the moving images. The famous scene from April 27th in Piazza Cavour, which shows violent charges of the police against students protesting the arrests of Franco Piperno and Antonio Russo, is filmed on more than one film camera to have more than one perspective and create a more complex representation of reality. What is less convincing are the interviews, filmed in similar fashion as mainstream news shows.

The element that led to the end of the newsreels experience is what Massimo Negarville referred to as the “problem of distribution and organization of cinematographic material,” which, if not solved in a timely way, “renders the work of filming and the montage useless.”62 It is vital for a political production to reach its audience, to make them the subjects and no longer the objects of a process of transformation. Only through direct contact with the masses can cinema call itself revolutionary, be judged as a source of change, and influence historical processes.

The Final Act

Newsreel practice did not stop, however. Some members of the Movimento Studentesco filmed two more productions: the first documented Richard Nixon’s arrival in Italy in 1969, after which there were clashes with the police in Rome, and the second was an attempt to reconstruct and analyze the political events of the Bussola. The objective of the student movement was really ambitious: to establish the truth over all the lies and atrocities that stemmed from the great American economic and military machine and its perfect workings. In February 1969, the President of the United States of America visited Rome. Extra-parliamentary forces called for a demonstration to be held in the capitol, which was full of extra police security, and the city thus became the backdrop for violent clashes. A group of students filmed the events. In Nixon (1969), the expressive editing style is enhanced by alternating between images of the presidential procession shown on TV and images of police brutality on the streets.

On December 31st, during the New Year’s Eve celebrations, another event upset the “tranquil bourgeois universe”: the place chosen to manifest the radical rejection of capitalist society was a famous nightclub, the Bussola in Viareggio. The damage was significant. A shot from a gun was fired into a student’s chest. Furious charges and dozens of arrests followed. Over the subsequent days the events were branded by the press as simple “hooliganism.”63 Therefore, the Movimento Studentesco felt the need to “clarify what the framework was that led to the actions at the Bussola.”64 Thus, at the beginning of 1969, the Anti-Imperial Committee of Rome65 set off for Pisa hoping to clarify the events of the Bussola and managed to use a Paillard to conduct a feature interview with Adriano Sofri, who led the Lotta Continua organization. In La Bussola (1969; “The Bussola”) there are some unique parts where there is a black screen with only the audio. This is how the lack of equipment produced stylistic solutions, which were adopted based on the limitations of production. The perfectly refined images of the official cinema were contrasted with the incompleteness, coarseness, and dirty style of the militant cinema. Even the audio in the interview is interrupted by Mason Williams’ “Classical Gas,” while images of glistening supermarkets full of people alternate with images of overworked manual laborers, to prove that “what unifies all these events is the shameless ostentation of wasted social riches.”66 Students, with the aid of their wide lenses and camera cars, visited the backdrops of important events to document the details of what had just occurred there, whether it was barricades or gunshots. Sofri concludes the interview by observing that the student movement did not manage to find a political response to the events but “the fact of searching for an answer in and of itself has been a chance for political growth.”67

Therefore, the experience of newsreels was brought to an end. The flow of students from the Movimento Studentesco into diverse political groups and the decision to bring together university and working-class groups meant the conclusion of what is considered the first experience of militant cinema in Italy, which began in 1968. Despite the proposal made by the Movimento Studentesco of Milan to create a national newsreel of the students’ movements, following the example of the students in Rome, the above-mentioned cases remained mostly isolated. Nevertheless, they represent an important witness of the militant cinema produced and made by the students in the 1968 movement.

Conclusions: What is Left?

The cinematographic practices we have analyzed, which led during the 1970s to other counter-informative activities produced from below thanks to the videotape, were the result of a multitude of individuals who, over two decades, continued to practice militant political action until they reached the foundations of what had previously been seen as unchangeable pillars of Italian society. They demonstrated that it was possible to unhinge its mechanisms from the inside, to imagine a counter-model for society, culture, and politics. However, the response of the political authorities, which would win in the end, imposed an “official” version of the events, demonizing the “internal enemy,” which was singled out as the one responsible for the chaos, and urging the public to request a return to order. This was why it was fundamental for the ruling class to plan the stream of information and realize the transformation of “real fact” to “news” through the selection and manipulation of the information given to newspapers and the television. The media singled out “the enemy” to the public, denounced it, and constructed a mono-dimensional vision of it.

What remained, then, of this experience? With the shift to lighter cinema, which was low cost and not as traditionally professional, one might well wonder if a work of counter-information using alternative sources could be made. In this occasion, we have to mention the “video activism,” the “digital transcription of a movement becoming a medium,”68 which, beginning from the 1990s, substituted what was regarded in 1968-1969 as the form of a militancy practiced in the field of cinema. In the Italian panorama, Alimonda Square in Genoa, where the killing of Carlo Giuliani took place in 2001, became the beating heart of a stream of antagonistic audio-visual practices. Other than being a big social event, the anti-G8 counter summit and protest was a once-in-a-lifetime media event: countless electronic eyes were fixed upon the experiences from July 2001, and the images created by the video activists contributed to the creation of a counter-current memory. Again, the intent was to produce an unofficial representation aimed at “telling what the media do not show, for they are imprisoned in the rules of the communication-entertainment and of the scoop.”69 The images, in this way, aimed to uncover the truth, aided by the lightness of the new recording devices, from the inside of the events, favoring a different development of audio-visual documentation. The anti-G8 of Genova ended a season of tension and conflicts in a long chain of events, which, from the end of the 1970s, brought us to the first year of the 2000s.

Notes

- W. J. T. Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images, University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2005, p. 76.

- C. Zavattini, Appunti per un brindisi a Mosca, in M. Argentieri (edited by), Cesare Zavattini. Neorealismo ecc., Bompiani, Milan 1979, p. 319. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations from the original Italian are my own.

- P. D. Grant, Cinéma militant. Political Filmmaking & May 1968, Wallflower Press, London 2016, p. 11.

- G. Gambetti, Migliaia di notti e di giorni, in T. Masoni and P. Vecchi (edited by), Cinenotizie in poesia e prosa. Zavattini e la non-fiction, Lindau, Turin 2000, p. 46.

- Ibidem, p. 25.

- An address made in favor of Cinegiornale della Pace that appeared in Rinascita, 1962, now in M. Argentieri (edited by), Cesare Zavattini. Neorealismo ecc., cit., p. 237.

- E. J. Hobsbawm, Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century 1914-1991, Pantheon Books, New York 1994; Eng. tr., of It. tr., Il secolo breve. 1914-1991, Biblioteca Universale Rizzoli (BUR), Milan 1997, p. 268.

- An address made in favor of Cinegiornale della Pace, cit., p. 237.

- Ivi, p. 236.

- C. Zavattini, Contro il passato nel cinema, in M. Argentieri (edited by), Cesare Zavattini. Neorealismo ecc., cit., p. 263.

- Ibidem.

- Ivi, p. 261.

- Ibidem, pp. 259-260.

- Ibidem.

- Ibidem, p. 261.

- Id., Bollettino dei Cinegiornali Liberi, March 1969, now in M. Argentieri (edited by), Cesare Zavattini. Neorealismo ecc., cit., p. 297.

- Ibidem, p. 296.

- Survey “Quattro domande agli uomini di cinema,” in Rinascita, 25 August 1967, now in T. Masoni and P. Vecchi (edited by), Cinenotizie in poesia e prosa. Zavattini e la non-fiction, cit., p. 16.

- C. Zavattini, Contro il passato nel cinema, cit., p. 272.

- Id., Bollettino dei cinegiornali liberi, June 1968, now in M. Argentieri (edited by), Cesare Zavattini. Neorealismo ecc., cit., p. 298.

- Ivi, p. 299.

- Ibidem.

- Ibidem, p. 298.

- S. Parigi, Filosofia dell’immagine. Il pensiero di Cesare Zavattini, Lindau, Turin 2006, p. 293.

- C. Zavattini, Bollettino dei cinegiornali liberi, June 1968, now in M. Argentieri (edited by), Cesare Zavattini. Neorealismo ecc., cit., p. 296.

- Id., Bollettino dei cinegiornali liberi, March 1969, now in M. Argentieri (edited by), Cesare Zavattini. Neorealismo ecc., cit., p. 301.

- A document for a press conference in a Civis’s cinema in Rome in 1969, now in T. Masoni and P. Vecchi (edited by), Cinenotizie in poesia e prosa. Zavattini e la non-fiction, cit., p. 295.

- C. Uva, L’immagine politica. Forme del contropotere tra cinema, video e fotografia nell’Italia degli anni settanta, Mimesis, Milan 2015, p. 43.

- C. Zavattini, excerpt from the document of presentation of Cinegiornale libero del proletariato, in T. Masoni and P. Vecchi (edited by), Cinenotizie in poesia e prosa. Zavattini e la non-fiction, cit., p. 211.

- Id., Bollettino dei cinegiornali liberi, July 1970, now in M. Argentieri (edited by), Cesare Zavattini. Neorealismo ecc., cit., p. 305.

- A. Medici, L’operaio con la macchina da presa, in AA.VV., Ciak, si lotta! Il cinema dell’Autunno caldo in Italia e nel mondo, Libertà, Rome 2011, p. 24.

- C. Zavattini, Tre domande conclusive, in M. Argentieri (edited by), Cesare Zavattini. Neorealismo ecc., cit., p. 361.

- G. Hennebelle, La vie est à nous, Écran, 78 (74), 1978, p. 75, now in P. D. Grant, Cinéma Militant. Political Filmmaking & May 1968, cit., p. 7.

- P. Baldelli, A. Filippi, Cinema e lotta di liberazione, Samonà and Savelli, Rome 1970, now in V. Camerino, Il cinema e il ’68. Le sfide dell’immaginario, Barbieri, Manduria 1998, p. 99.

- Id., L’ideologia nelle strutture del linguaggio, in AA. VV., Per una nuova critica. I convegni pesaresi 1965/1967, Marsilio, Venice 1989, p. 375.

- A document presented in June 1968 at the Pesaro Exhibition, titled Cultura al servizio della rivoluzione in F. Rosati (edited by), 1968–1972: Esperienze di cinema militante, Monographical Studies on Black and White, Società Gestioni Editoriali, Rome 1973, p. 29.

- Cinegiornale del Movimento Studentesco n. 1, (film).

- G. Fofi, “Alla ricerca del positivo,” Ombre rosse, 8 December 1969, now in V. Camerino, Il cinema e il ’68. Le sfide dell’immaginario, Barbieri, Manduria 1998, p. 116.

- C. Uva, L’immagine politica. Forme del contropotere tra cinema, video e fotografia nell’Italia degli anni settanta, cit., p. 49.

- M. Negarville, “Atti politici. Il cinema e il Movimento Studentesco,” in Ombre rosse, 6 January 1969, p. 66.

- Ibidem.

- M. Bertozzi, Storia del documentario italiano. Immagini e culture dell’altro cinema, Marsilio, Venice 2008, p. 210.

- L. Althusser, Ideologia e apparati ideologici di stato, 1970, in L. Althusser, Freud e Lacan, Editori Riuniti, Rome 1976, p. 17.

- Cultura al servizio della rivoluzione, in F. Rosati (edited by), 1968–1972: Esperienze di cinema militante, cit., p. 26.

- Ibidem.

- Ibidem.

- Ibidem.

- Ivi, p. 27.

- Ibidem, p. 28.

- Ibidem.

- Ibidem.

- Ibidem.

- Ibidem.

- Ibidem, p. 29.

- Ibidem.

- Ibidem, p. 33.

- “Il cinema come fucile.” Interview to Ferdinando Solanas, edited by G. Volpi, P. Arlorio, G. Fofi, in Ombre Rosse, 7 April 1969, now in G. Volpi, A. Rossi, J. Chessa (edited by), Barricate di carta. “Cinema&Film,” “Ombre Rosse,” due riviste intorno al ’68, Mimesi, Milan–Udine 2013, p. 293.

- Cinematographic alternative to Hollywood cinema and mostly European art-film. Theory showed by Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino in the “Hacia un tercer cine” Manifesto of 1969 in n. 13 of Tricontinental.

- “Il cinema come fucile.” Interview of Ferdinando Solanas, edited by G. Volpi, P. Arlorio, G. Fofi, cit., p. 294.

- Cultura al servizio della rivoluzione, in F. Rosati (edited by), 1968–1972: Esperienze di cinema militante, cit., p. 30.

- M. Negarville, Atti politici. Il cinema e il Movimento Studentesco, cit., p. 61.

- Ivi, p. 63.

- Movimento Studentesco, Contributo alla discussione sui fatti della Bussola della Commissione stampa del Movimento Studentesco, document included in the Digital Collection section of the Franco Serantini library.

- La bussola, 1969, (film), archived at the AAMOD (Archivio Audiovisivo del Movimento Operaio e Democratico, Audiovisual Archive of the Labor and Democratic Movement) as Perché Viareggio.

- The committee, of which Maurizio Rotundi was part, was situated in Rome at Vicolo della Penitenza n. 30. Interview with M. Rotundi, 1 February 2017.

- M. Studentesco, Contributo alla discussione sui fatti della Bussola della Commissione stampa del Movimento Studentesco, cit.

- Ibidem.

- En. Tr., E. Menduni, Il movimento si fa medium, in T. Harding, It. tr., Videoattivismo. Istruzioni per l’uso (edited by E. Menduni), Editori Riuniti, Rome 2003, p. 12.

- G. Verde, in http://www.verdegiac.org/sololimoni/index.html.