Before accepting the invitation to participate in the discussion entitled “Transformations without Revolutions?”, I hesitated quite a bit.1 On one hand, the re-introduction of the question of whether it still makes sense to think about revolutions, by questioning the transformations that may arise from them, attracted me. On the other, however, the suggestion that I speak at the encounter was inspired by my hypothetical contribution based on the fact that from the early 1980s my research interests, as well as a large part of my political activity, focused on the feminist critique of science. This is a field in which it might appear difficult to trace decisive transformations produced by the feminist revolution. In reality, this revolution created great and extensive developments, however, in the sciences the paths have increasingly strayed from the initial push for radical change, adhering to perspectives that seem like normalization to me. Regarding their internal criteria, the results of these processes appear to be quite satisfactory; therefore in their case, the expression “transformations without revolutions” could be appropriate. But in other cases? What about the currents that saw, at the beginning, the critique of science from a gender perspective as one of the many strands of a large current of movements that set out to “change the world”?

It seemed to me that this other question ‘revolutions without transformations?’, could be added to the one suggested by the original title. And since this was precisely the question that intrigued me more, I chose to accept the invitation to rethink if, and how much, that initial enthusiasm still make sense to me, and if, and how much, this perspective might still be an effective perspective for today’s world.

My remarks will focus on the 1980s, both because of the intensity with which I lived that period and the new horizons that seemed to burst open at the time, as well as because I think those years were decisive for the development of different orientations within a initially shared matrix regarding the desire to question the interplay between women, gender and science. In the section on the manner in which reformist and revolutionary paths were formed, we shall see how the triad I just mentioned was dismantled to address the issue as “women and science” on one hand, and “gender and science” on the other.

In my opinion this separation took power away from both the women’s movement – which was starting to move more and more clearly towards a claiming of space in science as we see today, moving away from the original critique of science as androcentric – and the feminist movement that found itself gradually more and more distanced from the sensibilities, experiences, and aspirations of women who were being recognized in increasing numbers in scientific research thanks to their identification with the concept that being female or male doesn’t matter in performing excellent research. If anything, both were, and are, aware that deep disparities continue to exist in the conditions in which they work, from the ability to obtain funding, to corporate relationships, and career possibilities. These are the main constraints they experience and fight against.

I think, instead, that the key issue concerns confidence in the neutral character of scientific knowledge merely based on the faith that it is objective. This is the issue that I plan to discuss in more detail. I believe that the gendered critique of science, as it was elaborated in numerous feminist scholar’s studies from the end of the 1970s and particularly in the 1980s, is still current today. It remains an extraordinarily fruitful prospective with which to dig into history. Above all, it allows us to reread the present as an unnecessary result of power dynamics that preserved male dominance under the guise of the universal, and to look for alternatives for which it makes sense to work in the future.

I realize that all this is marked by my subjectivity and my experiences: existential, cultural and political. I do not think, however, that placing oneself in a context in the most critical manner possible means reducing one’s personal bias to the autobiographical. Relationships with the world continue to act around my subjectivity, and attempting to maintain awareness of the two extremes of these relationships – each one complex – continues to attract me on the experiential level even before the epistemological one. Moreover, from Sandra Harding’s studies of “standpoint epistemologies” to Donna Haraway’s studies of “situated knowledges”, we find a fascinating tension in the feminist approach from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s that desired to expand the confines of the traditional canons of knowledge, replacing the pretence of objectivity with the research for self-conscious subjectivity.2

Among the possible limitations I could identify in my paper, I wish to declare at least two. The first is temporal and related to the decreased attention that I have devoted in the last few years to recent versions of the “women, gender, science” issue in the presence of what felt like the elimination of the revolutionary potential inherent in referring to the category of gender and gender sensitivity. I will return to this issue further on. The relationship between women and science interests me less and less, because its radical turmoil appears less and less alive. A second limitation regards a geographic positioning experienced in a somewhat contradictory manner. In the beginning of the 1980s, in fact, it was clear to me that the most pressing and innovative stimuli I could find were from scholars from the United States for the most part; but I desired to interact with Italian feminism with which I could significantly relate in political terms. I will mention later the importance that the radical upheaval, in the form of science and technology critique, had in Italy, which appeared particularly after the Chernobyl disaster. Like many other movements, this was also reabsorbed by the 1990s, and the general feeling of widespread awareness with which I had once nurtured myself seemed to disappear around me. On one hand, therefore, from the mid-1980s onward there was a kind of “Italian feminist critique of science” that still seems very interesting to me; which I do not regret having joined. But on the other it seemed to be a contingent occurrence, peculiar among many, so that the bias of the approach is marked by it, as it is marked by the substantial outdatedness that I indicated above as a temporal limit.

Auto-Representation and Revolutionary Intentions

In the text that Sabrina Marchetti, Vincenza Perilli, and Elena Petricola sent us before the symposium, I felt particularly attuned to the opening lines: “many of the movements and mobilizations of the last part of the last century were put forward and auto-represented as revolutionary”.

It seems important, now, to think about the intentions and prospects according to which individuals and groups acted in a more or less recent past. Asking these questions seem all the more important in the field on which I focus here, “women’s movements, feminism, gender, science”, in their various articulations.

Evelyn Fox Keller was a key figure not only for her research on gender and science, but also for the courage with which she made the feminist argument that “the personal is political” her own. In a book that quickly became a fundamental text and is now widely translated, in the mid-1980s she wrote:

The political ferment of the 1960s that helped to fuel recent developments in the social studies of science also gave impetus to the women’s movement, and, in turn, to the development of feminist theory. A principal task of feminist theory has been to redress the absence of women in the history of social and political thought.3

The reference to the political turmoil of the 1960s and the desire to place the development of feminist theories within the context of the women’s movement expresses, in my opinion, a way of being attentive to historical dynamics as well as the possibility of using these dynamics as transformative agents, even intent on “changing the world”. Nowadays, many feel that these are empty words. Many people say that they did not have sense even then, that they were simply manifestations of youthful excesses. But honestly, when one goes to investigate these traces, studying the times and methods, as well as the subjectivity that was developing, one can not deny that they had rather solid roots. Actually, they shared the same energy and self-awareness that many movements were using to rising up against centuries-old powers and privileges, such as patriarchal, ethnic and racist, colonial and imperialist ones.

Gender and Science: What Are the Dynamics between the Reformist and Revolutionary Approaches?

The pathways along which people have attempted to pursue change are numerous. I would like now to introduce the separation of two perspectives in particular, acknowledging at the same time that the operation of briefly describing the many faces of cultural and social phenomena, as well as individual and collective experiences, is too rigid and totally inadequate, particularly in regards to how they change over time. However, this simplification is not only useful, but also corresponds to the recognition of a junction that many feminists were discussing in the mid-1980s.

Although I do not think it makes sense to look for a single moment from which everything arises, there are occasionally texts that have marked or signalled a new position with particular effectiveness. So, in order to characterize the beginning of a phase in which many wanted to represent their relationship with science as revolutionary, and tried to orient themselves as such, I choose to refer to the epistemologist Sandra Harding, who in 1986 published the volume The Science Question in Feminism.

Even in the first few lines of the preface we read:

Since the mid-1970s, feminist criticism of science have evolved from a reformist to a revolutionary position, from analyses that offered the possibility of improving the science we have, to calls for a transformation in the very foundations both of science and of the cultures that accord it value. We began by asking, “What is to be done about the situation of women in science?” – the “woman question” in science. Now feminists often pose a different question: “Is it possible to use for emancipatory ends sciences that are apparently so intimately involved in Western, bourgeois and masculine projects?” – the “science question in feminism”.

The radical feminist position holds that the epistemologies, metaphysics, ethics, and politics of the dominant forms of science are androcentric and mutually supportive […] In their analyses of how gender symbolism, the social division of labour by gender, and the construction of individual gender identity have affected the history and philosophy of science, feminist thinkers have challenged the intellectual and social orders at their very foundations.4

Before focusing on the “revolutionary position”, I would like to propose two issues, which I will return to later. On one level, can we say that there was an “evolution” from the reformist position to the revolutionary one? I’ll tell you in advance that I instead believe that the events of the last thirty years have gone in the opposite direction if anything, because the reformist perspective very clearly prevails today. On another level, I think that the process by which, in a very short span of time (between the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s), “gender” became a category in the feminist critique of science that was used with firm self-assurance, merits investigating. This term recurs several times in Sandra Harding’s 1986 piece that I cited earlier, it was present even in the title of Evelyn Fox Keller’s 1985 volume, Reflections on Gender and Science from which I drew the earlier quotation… and I could retrieve many other instances. Thirty years later much has changed, both with respect to the type of reflections on gender as a plural notion, not reducible to the relationships between women and men, as well as in relation to how the radical value of ‘women and science’ has been weakened; this is another aspect that I will take up later because it seems important to develop it further.

A Historical Approach to the Revolutionary Perspective

According to Sandra Harding’s perspective, a revolutionary intent led feminists to challenge the very foundations of science as well as its socio-cultural status and power.

Thirty years have passed since feminist critique of science was a lively field of study and debate, particularly in the US, but also with important expressions in Europe and Italy (especially after the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, as we shall see shortly). I remember it as an exciting period, where the passion for different theoretical perspective was linked to the desire for a different way to regulate the impact of science and technology on human life and the environment.

It therefore seems appropriate to recall here some of the theoretical steps that I remember as the most important of that period. I do not believe, in fact, that they can be considered merely part of (or superseded by) history, particularly because the questions raised then, in my opinion, are still open. In addition, it does not seem to have left a significant trace, either in Italy or more generally in other countries of the world.

Principally two paths were followed, with many connections between them: one focused on the reinterpretation of historical processes; the other focused on questioning the epistemological and cognitive characteristics ascribed to modern and contemporary science. I will try to define them by referring in particular to two scholars, then perceived as disruptive – at least in feminist debate – and now assigned the more innocuous role of pioneers, almost too eager to be able to yet consider how well-founded their research was.

For the historical path I choose to quote Carolyn Merchant, author of The Death of Nature. Women, Ecology and the Scientific Revolution. This volume investigated the simultaneity and entwined reinforcement of the incipient capitalist revolution and the scientific revolution from the late 1500s to the 1600s, and later in the industrial revolution of the 1700s. The analysis focuses on the death of nature and the death of the female in the transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance that brought Europe from the widespread metaphor of the world-as-organism to the world-as-machine. In this manner, modern science in its very infancy freed itself from a respect for nature – the living body – and started to disassemble and reassemble it as a collection of inanimate parts, subject to the control and transformation of human intervention, following human purposes and projects.

“Human”, however, should be understood in the strong sense as “of men”, of males. The attention to the differences between the feminine and the masculine is very clear in Merchant’s book, as well as to the socio-historical construction of the roles and images attributed to them: the male entrepreneur in the public sphere; the female care-taker in the private sphere.

Merchant writes:

Feminist history in the broadest sense require that we look at history with egalitarian eyes, seeing it anew from the viewpoint not only of women but also of social and racial groups and the natural environment, previously ignored as the underlying resources on which Western culture and is progress have been built. To write history from a feminist perspective is to turn it upside down – to see social structures from the bottom up and to flip-flop mainstream values […]

Both the women’s movement and the ecology movement are sharply critical of the costs of competition, aggression, and domination arising from the market economy’s modus operandi in nature and society. Ecology has been a subversive science in its criticism of the consequences of uncontrolled growth associated with capitalism, technology, and progress.5

The first English edition of Merchant’s book was published in 1979, while the Italian translation, which came out in 1988, made it better known in the women’s movement here. It had already, however, been cited and discussed in Italy for several years, and many found valuable suggestions for developing a perspective that was feminist and environmentalist at the same time, a critique of science and technology’s claims of dominion. In my opinion, indeed, this was the significant peculiarity of the Italian situation, in which the push to question traditional knowledge structures and the condemnation of the serious problems inherent to the nature of modern and contemporary development projects were interwoven.

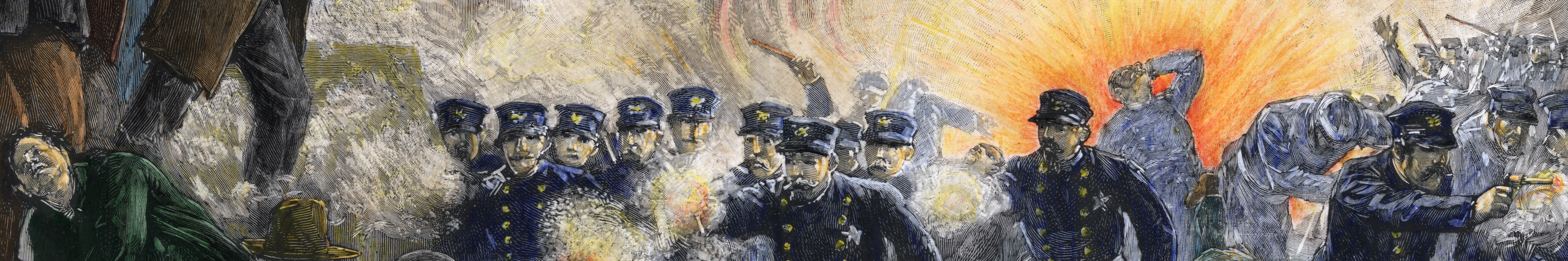

One could say that these were “subversive” positions precisely because they wanted to introduce the rejection of the concept of Promethean heroism and risk taking in social cultures and relationships, in the name of the awareness of limits. I will cite two texts as evidence of how a variety of women were involved in this phenomenon, as well as the commitment towards constructing both conceptual reinventions and practical changes. The first is entitled Scienza, potere, coscienza del limite (Science, power, awareness of limits) and contains contributions to a conference held in Rome in the beginning of July 1986, just two months after the Chernobyl disaster. In the second I myself write about “the itinerant knowledge of women after Chernobyl”, describing at least some of the initiatives that expanded rapidly in the first weeks, starting with the “Antinuclear laundry in Piazza Maggiore” in Bologna at the end of May, to the debate on the “wisdom of fear” in late June in Turin, and the debate on the “boundaries of progress” in Siena in August, and many others.6

The impact of The Death of Nature on the intersection of the women’s movement and the environmental movement took place – in my opinion – in the heart of Merchant’s work. Questioning the meaning and intent of the metaphorical shift from the world-body to the world-machine resulted in assuming the responsibility to subvert the social relationships and attitudes that had been imposed by centuries-old relationships of power. If this original and committed impetus left actual signs of radical transformation, is the issue I hope to address by moving closer to the current period.

It seems obvious that for Merchant, “to turn history upside down from a feminist perspective” meant recovering not only a different conception of history, in this manner, but also a different projectuality of the construction of the relationship between humans and the environment.

As she wrote with particular clarity in a passage that pulled together the pieces of the first decades of the triumphs of the development of science as a methodology for manipulating nature – from Francis Bacon’s project of domination found in his New Atlantis to the debate in which Newton’s mechanical approach prevailed over Leibniz’s dynamic vitalism – this process touched upon all levels, from scientific concepts, to social relationships, to world visions:

Between 1500 and 1700 an incredible transformation took place. […] The “natural” perception of a geocentric earth in a finite cosmos was superseded by a “non-natural” common sense “fact” of a heliocentric infinite universe. A subsistence economy in which resources, goods, money, or labor were exchanged for commodities was replaced in many areas by the open-ended accumulation of profits in an international market. Living animate nature died while dead inanimate money was endowed with life. Increasingly capital and the market would assume the organic attributes of growth, strength, activity, pregnancy, weakness, decay and collapse obscuring and mystifying the new underlying social relations of production and reproduction that make economic growth and progress possible. Nature, women, blacks, and wage laborers were set on a path toward a new status as “natural” and human resources for the modern world system. Perhaps the ultimate irony in these transformations was the new name given them: rationality.7

The Epistemological Approach

Rationality” could be used as the key word with which to move towards the epistemological approach. Here I choose to refer to a single author, despite my regret in condensing a theme that should be much more extensively developed. I have already mentioned Evelyn Fox Keller as the scholar who has perhaps had the greatest impact on research related to gender and science. Fox Keller’s vast quantity of publications, as well as the variety of issues that she raised, render her an indispensable point of reference in understanding how much has evolved since the 1980s. I’ll introduce her with another passage taken from Reflections on Gender and Science, a few lines after what I cited in the first paragraph:

The most immediate issue for a feminist perspective on the natural sciences is the deeply rooted popular mythology that casts objectivity, reason, and mind as male, and nature as female. In the division of emotional and intellectual labor, women have been the guarantors and protectors of the personal, the emotional, the particular whereas science – the province par excellence of the impersonal, the rational, and the general – has been the preserve of men.8

Here we find the issue in the feminist critique – the idea that science still adhered to this gendered canon – that men and women from within the world of science fiercely opposed from the very beginning. In addition, many feminists rejected the stereotype that the female brain is incapable of performing good science, yet, precisely because they were convinced that science is neutral, would not accept being excluded from it. In this regard, we must return later to the reformist perspective’s successes and the struggle for equal representation.

Keller investigated what she effectively called the “science-gender system” for years, using a psychoanalytic analysis of the formation of gender identity in childhood in which she deeply reflected on her own experiences as a mother of a boy and a girl. She found males tended to see the world as an object outside of oneself, and that females lived instead in relation to the world around them. In 1978 she wrote her first essay on this issues, using the word “gender” even in the title. She studied the development of objectivity in masculine identity through the dis-identification with the mother, as a prelude to the skill of detachment that is considered constitutive in practicing science.9

Describing the richness of the Keller’s ideas would require a lot of space, but would also be very useful for addressing the far-reaching issues which the feminist debate began to abundantly treat, yet today seem to put aside. One of the themes on which Keller tenaciously worked was the excavation of the historical genesis of the distinctive attribution of objective knowledge to science, according to a criterion that would become absolute, unambiguous and universally valid. At the same time, her writings are always marked by a very lucid awareness of how profoundly the most abstract and pure provisions of scientific rationality are not at all neutral. Instead they reflect the gendered characteristics in which the masculine developed in Europe and the United States in the modern age, and that reorganized the ancient rule of the patriarchy.

Two titles provide us with a small sketch. In the essay “The Mind’s Eye” that Fox Keller wrote with Christine R. Grontkovski – founded on the analysis of the bond that Plato established between the mind and the intellect, as well as the desire to obtain the purest form of knowledge by breaking away from the materiality of the senses – the authors highlight the fact that in modern science the scientific concept of objectification separates the subject and the object, “the individual who perceives and the object that is perceived”. In addition, we find “the separation of knowledge from the unreliability of the senses or, so to speak, the dematerialization of knowledge”. In Descartes we find a firm affirmation of the first aspect: “by severing the connection between the ‘seeing’ of the intellect and physical seeing – by severing, finally, the mind from the body”. Some decades later Newton instead expressed a “profound preoccupation with ‘looking’” that “seems to have had more to do with the inner eye than with the outer eye”, so much so that it was said that for Newton “The ideal of science was to ‘see’ what God ‘saw’”.10

Three centuries later, this dual rupture seems to have been restructured, replacing objectifiability with knowability, Keller and Grontkowski write. In my opinion, at this point we need to ask several questions. How far has the scientific imagination’s process of abstraction and dematerialization progressed, accompanied by a continuous creation of images that replace reality more than they propose to represent it? How much does the virtual feed on the far more tangible and concrete processes of appropriation and transformation of natural and human resources, in addition making every effort that they remain in their distressing situation of exploitation and invisibility?

Even this discussion, like many others with a gender perspective, is not neutral. Quite the contrary, at the end the authors outline a complex analysis of the “question of a possible male bias to an epistemology based on vision”. The passage that seems most interesting to me is the following: “in relegating the now submerged communicative aspects of visual metaphor to the realm of thought, the latent eroticism in such experience is protected against total disembodiment”. Drawing on Keller’s reasoning in the 1978 essay “Gender and Science”, the two authors continue:

The net result of this disembodiment is the same […] as that implied in the radical division between subject and object assumed to be necessary for scientific knowledge: Once again, knowledge is safeguarded from desire. That the desire from which knowledge is so safeguarded is so intimately associated with the female (for social as well psychological reasons) suggests an important impetus which our patriarchal culture provides for such disembodiment.11

The Gender Perspective and the Gendered Patriarchal Relationship in the Domination of Nature

Evelyn Fox Keller’s second text that I would like to, at least briefly, present here immediately appealed to me as soon as I heard about it, even from the title: “The Paradox of Scientific Subjectivity”.

It opens with a re-reading of the debut of painting’s now classical ‘perspective’ in the 1400s as well as that of modern science in the second half of the 1500s. In both cases, the paradox of subjectivity is addressed. As for painting, the invention of the perspective technique instigated the recognition of the differences we find if we change our viewpoint. At the same time, however, the obeying of procedures that follow the geometric laws of viewing nature built a new type of veracity, found in “the vantage point of a particular somewhere at least the tacit promise of a view from nowhere”. It seems interesting that even here, as in the essay “The Mind’s Eye”, the question of the foundations of the criterion of objectivity is discussed on one hand by dematerialization, and on the other by emphasizing the depersonalization of the process of vision.12

Moving from its beginnings to modern science, focusing on the historical shifts that took place from the 1600s to the 1900s, Keller examines the progressive disembodiment and dislocation of the scientific observer. Figures such as Descartes and Robert Boyle are reinterpreted within the process of the construction of an increasingly abstract and dispersed scientific subject. The closing pages provide, in my opinion, some important insights. The idea that dematerialization was necessary for the independent births of computer science and molecular biology does not hold if one takes into account that instead

they emerge from the arts and artifacts of human industry, expressing human needs and desires.

They are affected by material and social practices that are themselves both enabled by and enabling of a tradition of representation that has sought for more than 300 years the erasure of all evidence of the human agency behind both the practices and the representations.

Ultimately, what is at work today is “an ultra-modern rather than post-modern sensibility”.13

Why did I want to present this particular work of Keller in which gender isn’t mentioned, rather than others where the question is explicitly at the center of the analysis, as in “Making Gender Visible in the Pursuit of Nature’s Secrets”14 or “How Gender Matters. Or Why is it so Hard for us to Count past Two?”,15 or numerous others that I could cite? And why does the radical version of the science question in feminism seem so relevant to me?

The answers are obviously intertwined. It is not necessary to constantly proclaim what you intend to do when addressing issues from a position that is a strongly informed by gender. This was even less necessary in the 1980s, when for many the feminist perspective was so merged with their sense of self that they did not need to declare it, they just used it. In addition Keller – at least as her research appeared to me, but also in interactions with her16 – eschewed labels and ideological identifications, and always choosing to dig deeper into the issue, plunging boldly even into thorny ones.17

Moreover, the undeclared subtext of the article “The Paradox of Scientific Subjectivity” seems to provide answers regarding the characteristics and history of that paradoxical subjectivity that is elsewhere an explicit theme, while here it is implicit. Keller worked extensively on the link between male identity and presumption of being able to draw on objective knowledge, the pure rationality of the disembodied mind. Therefore, the crux of the paradox is that the absolute and universal canon of objectivity reflects the particular and partial subjectivity that shaped the identity of the male gender.

The final consideration regarding the fact that “an ultra-modern rather than post-modern sensibility” is in act today, in my opinion, reinforces the interpretation that I’m providing, and permits me to switch to another aspect: the relevance of this analysis for understanding the feminist viewpoint of modern and contemporary processes in the relationship between science and society. In fact, characterizing current sensibilities as ultra-modern means they have pressed even further, yet remain in the wake of the project of modernity. In techno-scientific terms this means that it has not moved away from project outlined by Bacon for man’s manipulation and domination of nature.

Of Bacon’s many works, as I mentioned above, Merchant devoted a chapter of The Death of Nature to a re-reading of his New Atlantis. Also in Keller’s Reflections on Gender and Science we find a similar attention to Bacon in the chapter “Baconian Science: The Arts of Mastery and Obedience” which focuses on another of Bacon’s works, Temporis Partus Masculus or The Masculine Birth of Time, written in 1602 or 1603 and not published in Bacon’s lifetime.

What was emerging was therefore a masculine, virile science. In the first section there is a man who turns to God in prayer, in the second we find “the voice of a mature scientist addressing a son, his virile offspring”, while Nature “becomes indubitably female: the object of action”. The following is taken directly from Bacon’s text: “I am come in very truth leading to you Nature with all her children to bind her to your service and make her your slave”.

Here nature must become a slave, whereas elsewhere she is more graciously betrothed. Keller, however, stresses that

Not simple violation, or rape, but forceful and aggressive seduction leads to conquest […] The distinction between rape and conquest sometimes seems too subtle. There remains something of a puzzle […] The metaphor of seduction, even forceful and aggressive seduction, does not seem adequate to all the ambiguities that are intended. Indeed, in the context of so limited a metaphor, the ambiguities become contradictions. Science has to be aggressive, yet responsive, powerful yet benign, masterful yet subservient, shrewd yet innocent.18

It clearly emerges that modern science was invented by its founding fathers under the sign of a strongly male sexual and virile imagery. This was not merely a linguistic aspect, but deeply entwined in the patriarchal exercise of power over women by men. Merchant offers us other impressive examples by highlighting passages in which Bacon compares methods used to investigate the secrets of nature to instruments of torture used in the witch trials. Or in even stronger sexual terms he writes: “Neither ought a man to make scruple of entering and penetrating into these holes and corners, when the inquisition of truth is his whole object”.19

If Keller’s evaluation of the ultra-modern character of the contemporary age is well-founded (as I believe), then even the expansion of the dematerialized economy, through financialization on one hand and virtual technologies on the other, should be questioned regarding its maintenance, or not, of global social relations. Among these social relations, gender relations continue to be a crucial aspect of the scientific system, and continue to act through conceptual and operational structures that are steeped in male-dominated and patriarchal perspectives.

The Woman Question in Science: Successes of the Reformist Approach

In the same decades, the women’s movement gained force for its claim to full rights of access to scientific training, and to work, equal to men, in all research fields. In the context of a more general process of emancipation and the promotion of affirmative action to ensure the effective possibility of equal opportunities, the presence of female researchers has quickly grown in the so-called ‘hard’ sciences, not only in the humanities. Between the late 1800s and the initial decades of the 1900s, certain women came to the fore who would leave their trace among the outstanding names of science; who in most cases had to courageously face thousands of obstacles and demonstrate a remarkable dedication to their studies: Sofya Kovalevskaya, Maria Sklodowska Curie, Emmy Noether, Lise Meitner, and later in the century, Barbara McClintock, Rita Levi Montalcini …

The real success of the reformist perspective, however, is not how the number of women scientists who become famous or who have been awarded the Nobel Prize has grown, but rather that the choice of a woman to engage in a scientific or technological profession is now recognized as “normal”. In good measure this is happening despite deep male resistance, both in defence of the polarized widespread imagery of the two genders, as well as more concretely in defence of the economic and social privileges that they still enjoy. But what does this imply for the reformist path that pursues “normalization”, understood as the recognition of the ability of a woman to conduct science on par with men not as a exceptional condition, but rather precisely normal?

In my opinion this is a crucial question, because it reveals how fully the revolutionary and reformist paths have strayed from each other. In fact, wanting to conduct science like men, and claiming to be capable, empties the revolutionary approach to the feminist critique of science of meaning. In fact, the demands and perspective of equal opportunity presuppose that science can be performed by women as well as men because science is objective and as such is neutral. Who practices it does not matter, what matters is only the unequivocal correctness of the implemented logical and experimental procedures.

In this manner, the two paths – that had had a common origin in women’s discomfort “in men’s laboratories” in the 1970s and 1980s – divided. Women were treated as an unwelcome presence, forced to stay in their place through condescending paternalism or the harsh rule imposed by a domineering boss. Female students experienced problems even in the first steps of research, and perceived an atmosphere tinged with derision (“in any case she will not make it, devoting oneself to science is not womanly”), so that one always felt out of place.20

This foundation shared both by feminists engaged in the demand for equal opportunity and affirmative action, and by feminists engaged in radical critique of the meaningfulness of the pretence of the univocality, uniqueness and objectivity of science, was therefore a powerful common element, which at the same time called for comparison. This, in fact, stimulated the recognition of similar subjective experiences, as well as the differences of the choices that were seen as priorities, and for several years both sides felt the need to maintain an open dialogue. In Italy, for example, from the mid-1980s to mid-1990s the “Coordinamento nazionale donne di scienza” (National coordination of women of science) was created, that promoted lively debates, organized public events, and produced material on topics such as bioethics.21 The criticism of the difficulties they faced, and the growing awareness of their own abilities and rights, led the majority of feminists engaged in science to become more resolute in standing up to the machismo in laboratories, research, as well as the organization and production of research. Successes grew as the number of women scientists, whose name appeared in the media, who were interviewed, and whose photos were published, grew. Meanwhile, the image of scientific research softened, many scientists proposed and practiced less competitive and aggressive, and more cooperative, models.

Of course we must ask ourselves how much these characterizations are appropriate, or whether they continue to adhere to stereotypes, that even within an improved social and cultural status still confer to the feminine the privileged role of knowing how to create good collective performance and how to build relationships. I am certainly not unhappy that these attitudes prevail among women, for complex historical reasons, not for biological reasons. But I would prefer that they not remain only women’s prerogative, a load that they alone must bear, while men continue to be reserved much broader spaces that are free from responsibility.

Power Relations and the Claim that “There Is No Alternative”

The 1960s saw the emergence of innovative research in the history and sociology of science. In particular, the text that perhaps received the most attention, engaging not only academics but also popular culture in fierce debates, was The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas S. Kuhn. In this study, Kuhn demonstrated that scientific revolutions (like the Copernican revolution that replaced the heliocentric with the geocentric vision) cannot be explained only from within science itself, according to the traditional conception of scientific historiography. They are not autonomous processes in which “a better theory”, or even “the best theory”, is established based on scientific criteria. Instead broader changes taking place in the ways of organizing knowledge, in different interpretations of the world are at play, a “paradigm change”. “Paradigm” and “paradigm change” have since become widely used expressions. They refer to all the cultural, social, political factors that shape worldviews, and that must be investigated in order to understand how these factors mutate over time.22

In her presentation at the conference to which my reflections in this paper are tied, Valeria Ribeiro Corossacz discussed women’s reproductive rights in Latin America and the Caribbean. I think that even in the feminist critique of science, the unequal power relations between the North and South should not be ignored, as well as the pretence of exporting the Western developmental model as the only model possible. “There is no alternative”, this is how it is and this is how it should be, war is inevitable…as well as the many other destructive facets of the TINA acronym. How much this has been, and is, devastating for societies in the southern hemisphere, and particularly for women, has been documented in the numerous studies on the effects of the imposed transition to a market economy in Africa or India, which has engulfed subsistence economies and the very possibility of women being protagonists of food production. We can refer simply to Vandana Shiva, activist and scholar, engaged for years in criticising how the so-called Green Revolution and the introduction of genetically modified organisms (GMO) is producing disasters in India, for humans and the environment. Her theoretical production now counts dozens of titles; here I would like to mention one that will allow us to explicitly return to the relationship between science and power: Staying Alive. Women, Ecology and Surviving in India.23

A critical approach from the South of the world can demonstrate more clearly how the mechanistic revolution was not “necessary”, nor was Galileo and Newton’s science right in itself, but grew out of the particular pressure of the industrial revolution in England to have new machines and energy sources; or how today’s biological, genetic, chemical research are fed by the thrust of fertilizer and drug multinational need to hoard new patents. In this sense, the sciences and technologies are maintained by the economic power and interests of the market. However the inverse relationship is also in act: science and technology, in turn, support current social and economic conditions, as well as the dynamic of impressing the idea that they are necessary.

A prime example is what is inherent in adhering to the idea that there is no alternative. As I discussed above based on Merchant and Keller’s feminist critique, modern science (but also contemporary science, following Keller evaluation’s for which it is ultra-modern) distinguishes itself from any other form of knowledge because it is objective, unambiguous, and universally valid. These are the articulations that can lead to tragic consequences such as the perspective on wars. Once one absorbs them psychologically as necessary, they are considered just and any hesitation falls away, alternatives are no longer sought that should instead always be pursued.

Two Paradoxes and Many Open Questions

Let’s return to division of the reformist and revolutionary approach. In reality, it was the first – not the second – to produce a revolution in the relationship between women and science. This so much so that in a sort of evaluation written at the beginning of the new millennium, Evelyn Fox Keller, after recalling how the number of female researchers in various fields has increased, stated that “Without question, the influx of women into the profession has changed the profile of American science at least”. Soon after, however, she asks:

has it in any observable way changed the actual doing of science? One might argue that changing the face of science does in itself change the doing of science, but not, I believe, in the ways people tend to think of first. What is usually understood by this question is: Have the women themselves changed the doing of science? Have they by their own example brought a new legitimization of traditionally feminist values into the practice of science? Thus posed, my guess would be: probably not. […] As the most recent group to be integrated, women scientists are under particular pressure to shed whatever traditional values they may have absorbed qua women – if for no other reason than merely to prove their legitimacy as scientists.24

The last observation seems particularly important to me. I would like to add that the pressure on women to integrate, to assimilate to male models is even stronger in scientific disciplines because they have been shaped as neutral for centuries, and are conceptually and culturally perceived as such.

Here the first of two paradoxes that I would like to point out emerges: a revolution took shape through the reformist path, which sounds like a contradiction in terms. However, it was a revolution in the Kuhnian sense, a paradigm change. Social changes (in any case slow and with a maddening succession of backlash, of constant stop and go) have acknowledged that women have equal rights, in different manners and to different degrees depending on the different societies and cultures; including the right to participate in scientific professions. However, the fundamental aspect of the idea that science is objective has not changed. To the contrary, precisely because women scientists made it their own, they were able to revise the 17th century canon by taking advantage of the corollary concept that science is neutral. Reconsidered today, it seems that in fact a fallacy was generated, if not more explicitly a contradiction: were the characters of objectivity and impersonality applied only because only men were granted the privilege of being able to practice science? Merchant and Keller provide convincing social and cultural answers. It is precisely the shift in these contexts that is creating a different scientific practice today, which has opened to the presence of women. The paradigm has changed, because the neutrality attributed to science was fully deployed. The core identity of science did not change; to the contrary it has strengthened its distinctive identity as the unique form of objective and universal knowledge.

There is a second paradox, which I find even more intriguing. In everyday language, but also in political terminology, “gender” often stands for “women”. To cite one case, the European Union often proposes programmatic guidelines called “Gender and science”, where the prevalent content consists in promoting affirmative actions to increase the presence of women in science and technology, or support them in career opportunities. Thus the “gender question in science”, in which Harding had perceived a transition to a revolutionary perspective, has been reabsorbed by the reformist perspective that has appropriated the term “gender”, thereby integrating and weakening it. As Keller writes, after almost two decades, starting from the perceived total irrelevance of those who tried to make the terms “gender” and “science” interact, in the beginning of the new millennium ““gender and science” has become the name of a respected academic sub-discipline: a well-established category of science studies”. Apart from wondering how much this could also be said for other countries – certainly little for Italy – it seems important to me that a little further in the text Keller remembers how at the beginning there were “three different lines of inquiry” along which the studies developed: “on women in science, on scientific constructions of gender, and on the influence of gender in historical constructions of science”. Keller then developed some observations, precisely on this last issue, that are marked by an optimism that quite surprised me. Returning to the question “has [the influx of women in the professions] in any observable way changed the actual doing of science?”, she writes:

But if we were to rephrase the question and ask, Has their presence helped to restore equity in the symbolic realm in which gender has operated for so many eons? I would answer with an unequivocal yes. Especially, I would argue that the commonplace presence of women in positions of leadership and authority in science has helped erode the meaning of traditional gender labels in the very domain in which they worked, and for everyone working in that domain. Furthermore, I would argue that this erosion has helped to open up new cognitive spaces and has thereby contributed to concrete changes in the very content of at least some scientific disciplines.

The text continues with examples of changes in biology, or in the study of reproductive processes, once one got over the gender bias that the egg was purely passive.25

In any case, the life sciences are often indicated as those in which women have exercised the most influence and have produced the most changes. In her, Has Feminism Changed Science?, also published at the start of the new millennium, Londa Schiebinger reviewed various disciplines noting how substantial changes produced by the different manner in which women scientists identify problems and seek solutions should be recognized in biology, ecology, primatology, and medicine. Often, the difference lies in the empathetic approach that leads to a connection with the research object, going well beyond the constraints of the experimental method that pretends a clear separation between subject and object. Far less positive are the assessments of the hard sciences, physics and mathematics. In this case it does not seem that the claim that they are pure and abstract can be undermined, therefore the issue of women’s presence at most arises in sociological terms rather than in scientific. How many are they, what paths have they taken (often teaching), what is their ability (equal to that of men?). Schiebinger evidences a sub-theme regarding physics which I think is very important: how are women involved in the intersection between physics research and military systems? From the 1940s on, the development of science – basic science as much as applied – has been fuelled by, and adapted to, military interests. In the US, the “military-industrial complex” continues to act as the most powerful force in directing and controlling scientific development. Women are included in these dynamics, whether they are aware of it or not.26

It is precisely because I feel that this issue of awareness is essential, that I would not fully adhere to Keller’s, Schiebinger’s, or many others’ optimistic assessments of ongoing processes, trusting in the great reach of the changes that could result from the increased number of women active in science and technology. I do not believe that mere numbers, or the desire to infuse greater sensitivity and different orientations into the way science is practiced, are enough to change the deep structure of the bonds that the sciences have with social, economic, and political interests and hierarchies. The very category of “gender” needs to be rethought in order to ask whether it is still capable of representing the complexity of auto-identifications and possible relations. In fact, in recent years it has been criticised by some of the same scholars who helped develop it. Joan Scott in her essay “Uses and abuses of ‘gender’”, observes in the first place that “gender”, nowadays accepted as a term, has lost its initial destabilizing force. However:

If we consider it a tool for understanding, not only the manner in which men and women are defined in their mutual relations, but also those interpretations of the social order that are contested, accepted, fought and defended in relation to definitions of male/female, we come to a new understanding of the different societies, cultures, histories and policies that we would like to analyze. […] Far from being a frustrating exercise, this approach opens the way for new ideas, new interpretations and perhaps even new policies. And far from being a term that is defined once and for all, as I once thought, gender remains an open question; when we think it has been defined, we know we are on the wrong track.27

From here I take the inspiration to add a note of optimism, despite the reservations that I expressed earlier on certain positive assessments. The fact that the revolutionary perspective of the “science question in feminism” did not obtain the same success as the reformist position – even running the risk of losing the term “gender”, emptied of its original meaning – does not mean that it was unrealistic or senseless. The complex process within “reformist” vs “revolutionary” dualism that I have summarized here, is itself one of the major limitations of the reflections that I have proposed. Therefore, I think that it is really important that research is conducted so that we don’t forget the multiple events, important figures, and movements that constituted the environment of growth and development. A prime example is importance of the feminist movement for women of science, which tried to draw a new shared source of strength and awareness of disadvantages through their interactions.

As for Italy, I think is important to stress that there are currently two research projects that are respectively investigating the National Coordination which met in Bologna from the mid-1980s to mid-1990s, and the Turin group “Women in Science”, formed – the first in Italy – in 1978, active until the early 2000s, which was particularly involved in the Coordination. Regarding the first case, Alessandra Allegrini has recently published a reconstruction of the interaction between the newly formed Turin group and the Bolognese group, up to the organization of a conference in Bologna in December 1986. As for the second case, Elena Petricola has analysed the Turin group; in 2013 a research report was released as a prelude for a larger publication.28

Towards a “Successor” Science?

From the very first discussions on the feminist critique of science alongside the commitment to investigate the historical and epistemological level, the relationship between modern and contemporary science and male dominance begged the question: so what? Can a feminine or feminist science be pursued? And is this what we want to do?

In the mid-80s Evelyn Fox Keller readdressed the book she published in 1983 on Barbara McClintock, and in Reflections on Gender and Science argued that McClintock’s particular way of conducting research – creating space for “a feeling for the organism” – should be read as a “commitment to a gender-free science”.

I suggest that the radical core of McClintock’s stance can be located right here: Because she is not a man, in a world of men, her commitment to a gender-free science has been binding; because concepts of gender have so deeply influenced the basic categories of science, that commitment has been transformative.29

However this was not only an interpretative hypothesis regarding McClintock; in this case Keller glimpsed the possibility of a different science, so that in the epilogue she wrote:

My view of science – and of the possibilities of at least a partial sorting of cognitive from ideological – is more optimistic. And accordingly, the aim of these essays is more exciting: is the reclamation, from within science, of science as a human, instead of a masculine project, and the renunciation of emotional and intellectual labor that maintains science as a male preserve.

[…] My vision of a gender-free science is not a juxtaposition or complementarity of male and female perspectives, nor is it the substitution of one form of parochiality for another. Rather, it is premised on the transformation of the very categories of male and female, and correspondingly, of mind and nature.30

Keller continued to adhere to this vision. In agreeing in 2014 to republish an essay from the early 2000s, she again reiterated that the project to be pursued remains that which she had intended in writing about Barbara McClintock:

To the extent that I aspired to a different kind of science, that science would be different by virtue of being gender-free; it would be a science practiced by both men and women in a different (gender-free) ideological context.31

A different path had already been outlined by Sandra Harding in The Science Question in Feminism, and was later discussed more fully in Whose Science? Whose Knowledge? Thinking from Women’s Lives. This scholar’s proposal can be summed up in the concept of “strong objectivity”, which replaces the impersonal objectivity prescribed by traditional male canons with a perspective that is presented as stronger because it includes the ability to think from within life experiences.

in a certain sense there are no “women” or “men” in the world – there is no gender – but only women, men, and gender constructed through particular historical struggles over just which races, classes, sexualities, cultures, religious groups, and so forth, will have access to resources and power. Moreover, standpoint theories of knowledge, whether or not they are articulated as such, have been advanced by thinkers concerned not only with gender and class hierarchy (recollect that standpoint theory originated in class analyses) but also with other “Others”.

[…] The notion of strong objectivity welds together the strengths of weak objectivity and those of the “weak subjectivity” that is its correlate, but excludes the features that make them only weak. To enact or operationalize the directive of strong objectivity is to value the Other’s perspective and to pass over in thought into the social condition that creates it – not in order to stay here, to “go native” or merge the self with the Other, but in order to look back at the self in all its cultural particularity from a more distant, critical, objectifying location.32

In Keller’s vision of a gender-free science, I find the risk of not holding actual historical conditions and their contingent character enough into account. The here and now in the sciences, as well as in various cultural, social, political fields and so forth, is still marked by deep power inequalities and asymmetries between women and men, and large areas of ignorance regarding the relevance of gender. Harding’s vision seems more attentive to precisely one of the most serious causes of fragmentation and conflict in the world today: the problem of the recognition of the Other, and the awareness of how ones identity is constructed in relation to ones relationship with the Other.

However, I do not find the last lines of the piece I mentioned above convincing. The proposal to think in terms of “strong objectivity” received a lot of criticism as soon as Harding developed it. The choice of a terminology that again returned to issues of objectivity, though modified, did not seem appropriate. It does not seem to me that the purpose to be achieved, by being aware of how much impact interdependence with the Other has, is to take on more distant, critical, objectifying location. I think that, indeed, an effective form of critical awareness of the partiality of ones own views and life experience does not require distancing oneself from either oneself or the Other, trying instead to keep in mind the intensity of these bonds.

I would like to outline a possible variation here that is inspired by the recent collection Writing about Lives in Science. (Auto)Biography, Gender, and Genre, edited by Paola Govoni and Zelda Alice Franceschi. In her introductory essay, Paola Govoni discusses how historiographical choices in general, and more recently those relating to the history of science in particular, have changed thanks to a new awareness of how the subjectivity of the biographer and his or her biographee affect them on one side, and how the relationship between the two subjects affect them on the other. I quote a short passage:

it is beyond dispute that over the past two decades scientific biography has significantly changed its role in the history of science, technology, and medicine. The need to re-examine the potential and the limits of the biographical genre in the sector of science studies arose in particular from the publication of biographies which showed themselves capable of successfully penetrating the complexity of creative processes and discoveries. […] This should lead us to consider that the relations between men and women biographers and men and women biographees may deserve more attention than they have received so far.33

Among the essays from this collection, I have already mentioned the piece in which Keller reaffirms her desire for a gender-free science through a reconsideration of her research on Barbara McClintock. Her discussion makes extensive use of autobiographical analysis presented as a drama in three acts, marked by different stages both regarding her relationship with McClintock and the reception – positive and negative – that her work would have in feminist and scientific circles.

It seems very interesting to me that another contributor to this volume, Pnina Abir-Am, investigates the different ways of writing history of science that can be set in motion if the dual relationship between the two subjectivities of the biographer and his or her biographees is activated. The author readdresses Pierre Nora’s notion of ego-histoire in particular and writes:

In addition to interrogating my change of historical strategy in writing the recent history of women in science, this essay also sizes an opportunity to experiment with ego-histoire, a new approach that has altered our historical consciousness by providing a theoretical justification for historians to include their own personal experiences with the historical events that they witnessed and write about. […] Situated between history and autobiography, ego-histoire liberates historians from the objectivist paradigm that forced them to ‘keep themselves out of the way of their work.34

Can we imagine a similar path to free scientists – not only historians of science – from the objectivist paradigm? To go beyond the separation of the active observer, woman and man, that with the eyes of a disembodied mind investigates a totally passive object? We could reconfigure the relationship as an open dynamic between two subjects that reciprocally change each other and whose respective peculiarities and degrees of autonomy are put into play; in the broadest sense, imagine their respective subjectivity.

This is merely a rough sketch of a possibility that I could imagine for the feminist critique of science, if one still wants to pursue some revolutionary transformation. In part it is similar to Sandra Harding’s proposal of the concept of “strong objectivity”, because the ideal of the observer-observed unidirectional objectivity is replaced by the interaction of two subjects. In part, however, it is also similar to some considerations present in Keller’s Reflections on Gender and Science:

In a science constructed around the naming of object (nature) as female and the parallel naming of subject (mind) as male, any scientist who happens to be a woman is confronted with an a priori contradiction in terms. This poses a critical problem of identity: any scientist who is not a man walks a path bounded on one side on inauthenticity and on the other by subversion. […] Only if she [a woman scientist] undergoes a radical disidentification from self can she share masculine pleasure in mastering a nature cast in the image of woman as passive, inert, and blind. Her alternative is to attempt a radical redefinition of terms. Nature must be renamed as not female, or, at least, as not an alienated object. By the same token, the mind, if the female scientist is to have one, must be renamed as not necessarily male, and accordingly recast with a more inclusive subjectivity.35

Keller’s book was published in 1985, where as Harding’s in 1986 and 1991. I believe, in any case, that the message is still current. The characteristics attributed to science on one hand, and to nature on the other, must be changed; reconceptualizing both of them as equipped with that form of subjectivity which I mention earlier, freeing them from the cage of gender stereotypes. From here, however, I do not believe that the shift to the vision of a gender-free science will be immediate. In today’s world – and I can not say for how much longer – it is likely that women will predominantly be the agents of change, and it is also likely that those of them that believe radical changes are possible will continue to draw strength from feminist perspectives and sensitivity to gender relationships.

Notes

- I would like to thank Daniela Crocetti for her thorough and careful translation.

- Sandra Harding, The Science Question in Feminism, Open University Press, Milton Keynes 1986; Donna J. Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism as a Site of Discourse on the Privilege of Partial Perspective”, Feminist Studies 14, p. 575-599, 1988.

- Evelyn Fox Keller, Reflections on Gender and Science, Yale University Press, New Haven 1985, p. 6.

- Sandra Harding see note 1 p. 9.

- Carolyn Merchant, The Death of Nature. Women, Ecology and the Scientific Revolution, Wildwood House, London 1979, p. xvi.

- Grazia Leonardi ed. , Scienza, potere, coscienza del limite. Dopo Cernobyl: oltre l’estraneità, Editori Riuniti Riviste, Roma 1986; Elisabetta Donini “Andar per scienza. Il sapere itinerante delle donne dopo Cernobyl”, Reti. Pratiche e saperi di donne, Editori Riuniti Riviste, n. 1, settembre-ottobre, pp. 19-22, 1987.

- See note 4, p. 288.

- See note 2, p. 6-7.

- Evelyn Fox Keller, “Gender and Science”, Psyschoanalysis and Contemporary Thought, vol. 1 september, pp. 409-433, 1978.

- Evelyn Fox Keller et al., “The Mind’s Eye”, in: Discovering Reality. Feminist Perpsectives on Epistemology, Metaphysics, Methodology and Philosophy of Science, Reidel, Dordrecht 1983, pp. 212-218.

- See note 9, p. 220.

- “The Paradox of Scientific Subjectivity”, Annals of Scholarship, vol. 9, p. 124, 1992.

- Evelyn Fox Keller, “Making Gender Visible in the Pursuit of Nature’s Secrets”, in: Feminist Studies/Critical Studies, University of Indiana Press 1986, pp. 67-77.

- Evelyn Fox Keller, “How Gender Matters: Or, Why It’s So Hard For Us To Count Past Two”, in: Perspectives on Gender and Science, The Falmer Press, Taylor and Francis Group, Philadelphia 1986, pp. 168-183.

- Elisabetta Donini, Conversazioni con Evelyn Fox Keller. Una scienziata anomala, Elèuthera, Milano 1991.

- Marianne Hirsch et al. eds., Conflicts in Feminism, Routledge, New York and London 1990.

- See note 2, pp. 37-39.

- See note 4, p. 168.

- Rita Alicchio et al. eds., Donne di scienza: esperienze e riflessioni, Rosenberg & Sellier, Torino 1988.

- Ibid.

- Alessandra Allegrini, 1978-1986: All’origine del Coordinamento Nazionale “Donne di Scienza”, FGB Fondazione Giacomo Brodolini, Roma 2013.

- Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1962.

- Vandana Shiva, Staying Alive. Women, Ecology and Surviving in India, Kali for Women, New Delhi 1988.

- Evelyn Fox Keller, “Making a Difference: Feminist Movement and Feminist Critiques of Science”, in: Feminism in Twentieth Century Science, Technology and Medicine, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2001, pp. 104-105.

- See note 22, pp. 105-108.

- Londa Schiebinger, Has Feminism Changed Science?, Harvard University Press, Cambridge 2001, pp. 164-170.

- Joan W. Scott, “Usi ed abusi del “genere””, in: Genere, politica, storia, Viella, Roma 2013, pp. 126-127. Translated from Italian by Daniela Crocetti.

- See note 19; Elena Petricola, Donne e scienza di Torino, dalla memoria alla storia, ArDP Archivio delle Donne in Piemonte 2013.

- See note 2, p. 174.

- See note 2, p. 178.

- Evelyn Fox Keller, “Pot-holes Everywhere: How (not) to Read my Biography of Barbara McClintock”, in: Writing about Lives in Science. (Auto)Biography, Gender, and Genre, V&R unipress, Goettingen 2014, p. 39.

- Harding, Sandra, Whose Science? Whose Knowledge? Thinking from Women’s Lives, Open University Press, Milton Keynes 1991, p. 151.

- Paola Govoni, “Crafting Scientific (Auto)Biographies”, in: Writing about Lives in Science. (Auto)Biography, Gender, and Genre, V&R unipress, Goettingen 2014, p. 8-9.

- Pnina Abir-Am, “Women Scientists of the 1970s: An Ego-Histoire of a Lost Generation”, in: Writing about Lives in Science. (Auto)Biography, Gender, and Genre, V&R unipress, Goettingen 2014, p. 226; Pierre Nora ed., Essais d’ego-histoire, Gallimard, Paris 1987.

- See note 2, pp. 174-175.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.